The Italian phrase in angustie means something like “in distress,” “in a tight bind,” or “under pressure from all sides.” Angustie derives from the Latin “angustus”—narrow—and is related to the words “Angst” and “anguish.”

In Domenico Cimarosa’s one-act opera L’impresario in angustie (first performed in Naples, 1786), the pressures being applied upon the central character—a man trying to run an opera company—come primarily from an inept would-be librettist, a composer whose previous opera failed, and three female singers: Doralba (singer of serious roles) and Fiordispina and Merlina (specializing in comic roles). They all pester the impresario with their divergent ideas about what the subject of the next opera should be, what musical elements it should contain, how the costumes should look, and so on.

Several of the characters engage in flirtations, and two of them end the opera with a duet in which they promise to marry each other. In short, Cimarosa’s farsa per musica is a comedy about life in an opera house, making it close cousin to Mozart’s Der Schauspieldirektor, Donizetti’s Le convenienze ed inconvenienze teatrali, Auber’s La Sirène, and Richard Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos.

L’impresario in angustie was a hit at the time, being performed in opera houses from Lisbon to Copenhagen and, in a translation by Goethe, at Weimar in 1791. It was sometimes expanded to two acts, with additional numbers by other composers.

I had to piece much of this information together myself (from Grove Music Online and from scores and early libretti online). The booklet essay is utterly inadequate: just a track list, short essay, and synopsis. (Though it’s honest about its inadequacy. It provides a bibliography, consisting of nothing but a single citation: the Encyclopedia Britannica, 1911 edition!).

I would have had an easier time if the track list had mentioned the characters whom we hear singing and had indicated whether that track is a recitative or aria (etc.). Similarly, the synopsis should have been much more detailed, with track numbers inserted at the appropriate spots.

True, Brilliant Classics does make an Italian-only (or, rather, Italian-and-Neapolitan) libretto available for download. But, perhaps to save space, the recitatives have been typeset as prose, disguising the verse meter and burying the rhyme words in the middles of lines. Also, Brilliant’s libretto is not divided into scenes, nor are there (again) headings indicating aria, duet, etc.

I also found myself wishing for an English translation, preferably one with footnotes explaining some of the wordplay and literary allusions. Or, if that’s too much to ask, then at least a translation into modern Italian of the often-lengthy passages that Don Perizonio (the would-be librettist) sings in Neapolitan dialect.

The seven singers are sopranos Paola Cigna and Lavinia Bini, mezzo Camilla Antonini, tenor Alejandro Escobar, baritone Marco Filippo Romano, and basses Carlo Torriani and Luca Gallo. The tenor (who plays Gelindo Scagliozzi, the composer) is from Colombia; all the rest are native Italians. They have fun conveying their characters’ shifting moods and qualities: wiliness, pompousness, resentment, teasing, and so on.

In purely vocal terms, all seven singers are quite capable, maintaining mostly steady tone and good intonation, and handling the brief florid passages adequately (if never with exquisite nuance). A few of them lack strength for the low notes in their respective role, but this never becomes unduly annoying. I’ve noticed that many singers nowadays take roles that lie a little low for them, perhaps to ensure that they can handle securely the high notes, which are more obvious to an audience.

The musical numbers are as charming and diverse as anyone might expect who knows Cimarosa’s most frequently recorded opera, Il matrimonio segreto. The latter has had at least six releases since late 1986—three CD recordings, and three videos/DVDs—in performances under such noted conductors as Barenboim, Maazel, and López Cobos. I have seen delightful productions of it at Berlin’s Deutsche Oper—starring Barry McDaniel as the scheming penniless count—and at the Eastman School of Music. Two other recordings, each conducted by Simone Perugini (here and here), seem to have been little distributed in North America. There is a DVD available (with, apparently, second-rate singers); another DVD (currently out of print) stars such major artists as Barbara Daniels, David Kuebler, and Carlos Feller. At the moment YouTube has the Daniels/Kuebler/Feller as well as two other performances (one audio-only, the other from a stage production). So you can certainly get to know Cimarosa’s strengths. (I’ll mention recordings of the present opera in a moment.)

L’impresario offers lyrical arias, dancelike ones, an occasional touching passage involving the chord on the flatted second degree (this chord is indeed known, in the music world, as “the Neapolitan”), some passages of rapid patter or repeated nonsense syllables for various characters (decades before Rossini’s Dr. Bartolo), and numbers involving four and five characters in lively interaction.

Cimarosa scored the work for the basic Classic-era forces of oboes, horns, and strings. The orchestra here (named after a renowned late-twentieth-century composer-conductor) uses modern instruments and plays neatly. The recording was made in a Milan studio in 2017, yielding a clear and well-balanced result: the orchestra is captured in full color, yet the voices also have nice presence. No effort has been made to indicate stage movement. The generally impressive results can be gauged by listening to the beginnings of each track here.

Of the several previous recordings, the only one currently available in North America comes from 1963, re-released on the Myto label. (Italians use the word “mito”—myth—to mean “legend” in the sense of “Maria Callas was a legend in opera.”) It features some internationally known singers, e.g., Dora Gatta, Sesto Bruscantini, and Italo Tajo. (Italo Tajo’s delightful and precise recordings of Mozart arias have been re-released in recent years.) The portions I’ve listened to are lively and well characterized but recorded in airless mono, with much stage noise and an oboist whose tone I find pitifully thin. A 1993 performance conducted by Fabio Maestri and released by Bongiovanni on 2007 seems currently out of print, but at the moment it can be heard on YouTube, which also hosts a video version (appropriately costumed and humorously acted), conducted by Riccardo Doni. In short, L’impresario in angustie may be Cimarosa’s second best-known opera today, after Il matrimonio segreto.

Anybody interested in trends in Mozart-era opera will want to hunt out the new recording (or the very engaging Myto re-release), along with such other comic operas from around the same time: Galuppi’s L’amante di tutte and Paisiello’s La grotta di Trofonio. As for opera lovers, generally, if they are not fluent in Italian and in Neapolitan dialect, they’ll at least keep noticing words and names that they recognize by ear: “duetto,” “libretto,” “bravo!,” “Andromaca,” plus “poeta” and “maestro”—the latter two here meaning “librettist” and “composer.” But I imagine they’ll feel frustrated by the lack of a translation.

The Brilliant Classics team might want to think about what makes a person buy CDs when he or she can instead stream the same audio content through Spotify or some other online service. Well-researched and user-friendly printed materials can turn a CD into a treasured possession, something to study in depth and to recommend to like-minded friends. And some of those friends may, in turn, then buy a copy of the CD, thereby keeping the record business profitable.

A final thought: This is precisely the kind of modestly proportioned opera that might be possible for regional opera companies and college opera programs to mount as the Covid pandemic gradually recedes. Perhaps the cast members could quarantine beforehand, and the chamber orchestra could be seated in a widely spaced arrangement—and, except for the wind players, be masked. Translate the thing into lively English and everyone would have a blast. People would learn how high the level of operatic creativity was in Italy during Mozart’s lifetime. And nobody would get sick!

Ralph P. Locke

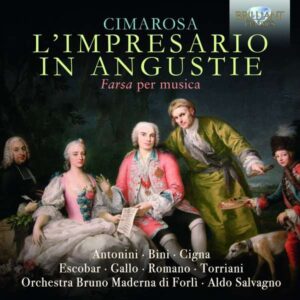

Domenico Cimarosa: L’impresario in angustie

Carlo Torriani, Marco Filippo Romano, Paola Cigna, Lavinia Bini, Alejandro Escobar, Orchestra Bruno Maderna di Forli, Aldo Salvagno

Brilliant 95746 [CD]

Click here for the complete libretto.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The review first appeared, in a somewhat shorter version, in American Record Guide and is posted here by kind permission.