Last April, writing in the Observer, Fiona Maddocks lamented her first Easter without the mysteries and joys of Bach. ‘This year all performances have been cancelled. Our lives have already been stopped by Covid-19. Churches and concert halls are shut. Choirs, large or small, professional or amateur, are silent. Battered vocal scores, marked up with “stand”, “sit” and other vital instructions, remain on shelves until next year. Musicians’ livelihoods have been shattered. The Passions are guaranteed dates in the diary, but I’ve never heard a musician speak of this music as mere work. Bach is in our souls and psyches.’

Maddocks’ article ended with hope: ‘Next spring, the singers and players will be back. Support them. They need you, but you may also find you need them.’ Well, she was right about one thing. The last year has shown us just how much we need musicians as surely as they need audiences – socially distanced, or just plain distanced. But, the notion that we might be back in concert halls and churches, that life might be in any way ‘normal’, has proven sadly over-optimistic.

However, Easter 2021 has not seen ‘Passions denied’. In fact, there has been a wonderful surfeit of Easter performances, live and recorded, streamed from around the globe, turning our homes for a short while into sites for spiritual renewal and reflection. A glance at the schedules seems to me to suggest that J.S. Bach’s St John Passion has topped the ‘online charts’ this Easter. On Good Friday, 297 years after it was first performed at Vespers at the St Nicholas Church in Leipzig, one could choose to hear Bach’s setting of the account of Christ’s Crucifixion as performed by Daniel Harding and the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra and Choir from Stockholm’s Berwald Hall; or tune into Battersea Arts Centre where Mark Padmore directed a performance with its readings, also singing the role of the Evangelist alongside the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment; or enjoy John Eliot Gardiner’s performance with his Monteverdi Choir and English Baroque Soloists, recorded in the Sheldonian Theatre in Oxford.

In fact, a closer look suggested that Oxford had won the venue prize. For on Good Friday afternoon, there were in fact two streamed performances from Oxford: that led by Gardiner from the Sheldonian and a performance in Christ Church Cathedral by Oxford Bach Soloists to open their four-day streamed Easter Festival, directed by Thomas Guthrie and conducted by Tom Hammond Davies. This double dose of Passions was given added interest because there were several overlaps between the casts of soloists with Nick Pritchard (Evangelist), Alex Ashworth (Pilatus) and Alexander Chance performing in both settings.

(To make the musical counterpoint even more dense, soprano Rowan Pierce and mezzo-soprano Helen Charlston could be heard singing both among the chorus in Christ Church and in solo roles in Battersea Arts Centre; and the evening before, the choir of Queen’s College Oxford were joined in the Sheldonian by the Oxford Philharmonic Orchestra for a Maundy Thursday St John Passion.)

One ‘advantage’ of performances streamed online is that there is often a wide window of opportunity during which to enjoy them, so there’s no reason why one shouldn’t surfeit on St John Passions this April. I plumped for Oxford Bach Soloists’ performance, tempted by its billing as an ‘enactment’. Not that there haven’t been staged St John Passion’s previously, but both Deborah Warner’s 2000 ENO staging and ETO’s ‘immersive semi-staging’ – seen at Hackney Empire last spring, then cruelly stopped in its tracks by Covid, only to re-emerge this Easter Sunday to launch ETO’s 2021 digital season (and now available online) – are large-scale affairs, whereas the smaller forces and potentially intimate camerawork at Guthrie’s disposal, and the necessary constraints of pandemic performances, promised to involve the viewer/listener in the narrative in new ways.

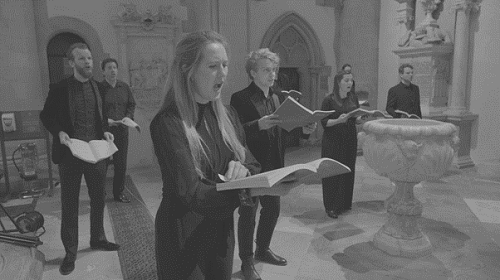

In his pre-performance introduction, Guthrie promised a “no hold’s barred, bird’s-eye view of the process of making this story”. And so, we saw the musicians, technicians and stagehands arriving – striding across the Tom Quad, unpacking instrument cases, re-arranging music stands, setting up lighting – the seemingly normal pre-rehearsal customs inter-cut with soft-grained black-and-white images of a lone figure, our Evangelist, seated inside the Cathedral, motionless, reflective, watching the interlopers whose movements disturbed the stillness.

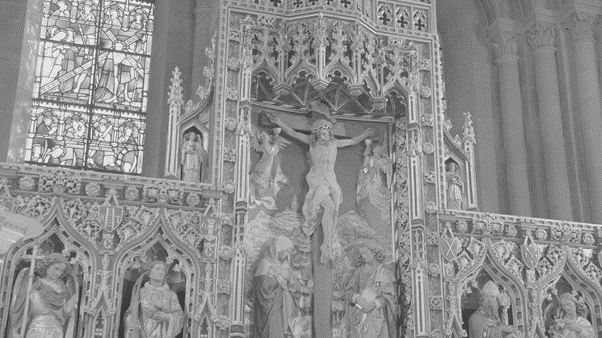

As he gazed down from the gallery at the busyness below, a sudden black screen initiated the performance, the sustained oboe nasality pressing urgently against the turbulent churning of the strings. There was a sense of turning the first a page of book, in both anticipation and trepidation for what the story would bring; or rather – when the images resumed and we found ourselves amid the players and singers strewn across the transepts, along the choir, in pulpits, beneath the tower – like the raising of a theatre curtain, whereupon we became both onlookers and participants in the unfolding drama. Cameramen moved stealthily around the standing instrumentalists and scattered singers, our gaze travelling through crowds, over shoulders, along pews, round the chancel arcades. At the heart of the dispersed mass, conductor Tom Hammond Davies threw his arms up towards the Perpendicular vaults, eliciting a glorious mass of sound: “Herr, unser Herrscher, dessen Ruhm/ In allen Landen herrlich ist!” (Lord, our ruler, whose glory is magnificent everywhere!)

There was a sense of unrest, though, as we surveyed close ups of the faces of those gathered to both watch and enact the events of Christ’s Passion, prudently deployed surtitles serving as a discreet guide. Amid the tension, there was stillness: Nick Pritchard’s Evangelist, a humble white-shirted figure amidst the sea of black, looked on in dismay and bewilderment, first standing erect, then kneeling as if in penitence. As the Passion progressed, monochrome, sometimes sepia-tinted, alternated with soft colour, evoking both stylised ritual and everyday humanity. During the choruses and chorales, the camera paused on the faces of casually dressed individuals – like us, side-line onlookers – who mouthed the English translations of the sung text, making them, and us, complicit.

Nick Pritchard’s Evangelist was a troubled storyteller, both within the action and without. Sometimes he sang directly to the camera, compelling the listener to follow and understand. At other times, he led us through the crowds who sing gentle chorales of devotion then bay for Christ’s blood – a misplaced wanderer, disorientated, perplexed, increasingly despairing, but always an unflinching narrator who knows his tale must be heard.

Pritchard has a beautiful voice, effortlessly clear and true at the top, always strong and even. He didn’t overly nuance the text but sang in idiomatic, natural German, making the language itself seem like music. This Evangelist’s vocal composure and very human physical gesture made the moments of musical intensity all the more telling. The wrenching anguish of Peter’s betrayal of Christ was deepened not, as is so often the custom by the vicious guttural articulation of the cock’s crowing – “Da verleugnete Petrus abermal, und alsobald krähete der Hahn” (Then Peter denied it again, and once the cock crew) – but by the poignancy and pain with which Pritchard imbued the disciple’s weeping, the melisma writhing through the chromatic contortions of guilt: “Da gedachte Petrus an die Worte Jesu und ging hinaus und weinete bitterlich.” (Then Peter thought of Jesus’s word and went out and wept bitterly). After the crowd’s self-intoxicating cries for Barabas to be released, Pritchard’s anger at their grotesque delusion was palpable: “Barrabas aber war ein Mörder./ Da nahm Pilatus Jesum und geißelte ihn.” (Now Barrabas was a murderer. Then Pilate took Jesus and scourged him.) At such moments, Pritchard was simultaneously our narrator, protagonist and theatre director, skilfully manipulating our emotions.

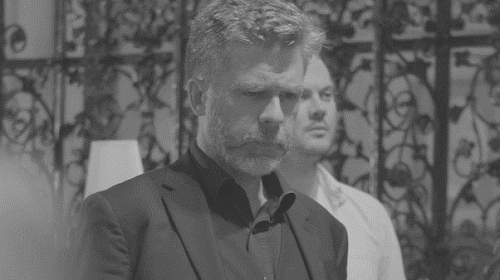

Around the Evangelist the action unfolded swiftly in a free-flowing cinematic montage, moving through the Cathedral’s chapels and aisles. Movements segued seamlessly with quasi-operatic momentum, sweeping up all in the inevitable progress towards Golgotha. We, too, experienced the confusion, anger and distress, the camera tugging us into the crowds, showing us the participants’ pain and fury. So, when in the opening numbers the people came searching for Jesus, we felt the strange and dangerous alchemy of the crowd, the claustrophobic intensity, and saw close-up the anxiety and knowledge etched on the face of Peter Harvey’s Christus.

Forced to confront his accusers, neither Harvey’s gaze nor voice faltered. His was an eloquent, very human Christ. Struck by a servant, he queried gently but confidently, “Hab ich übel geredt, so beweise es, dass es böse sei, hab ich aber recht geredt, was schlägest du mich?” (If I have spoken badly, then show what was wrong. But if I have spoken rightly,why do you strike me?) Our physical proximity to the exchange deepened our collusion in the sin, as was emphasised by the chorale which immediately ensued, ‘Wer hat dich so geschlagen’ (Who has struck you in this way?), the sparse accompaniment of the second stanza exposing the undeniable collective guilt.

Yet, Christ revealed his self-certainty too, assertively answering Pilate’s questions in the court with dismissive conviction and an almost threatening assurance: “Mein Reich ist nicht von dieser Welt” (My kingdom is not of this world). No wonder Alex Ashworth’s Pilate was so unsettled. “So bist du dennoch ein König?” (So you are then a King?), he faltered. “Du sagst’s, ich bin ein König.” (You say it, I am a king.), came the unnervingly sure reply. Such strength made Christ’s ultimate words almost unbearably vulnerable, the prone figure addressing first his mother, “Weib, siehe, das ist dein Sohn!” (Woman, look, this is your son!), then a disciple, “Siehe, das ist deine Mutter!” (Look, this is your mother!), with sincerity and love.

Alex Ashworth was a superb Pilate, his leadership dignified, his doubts and weakness convincing and touching. His sympathetic conversation with Christ, disrupted by the violent intrusions of the blood-seeking mob, found its true expression of faith in the subsequent chorale, ‘Durch dein Gefängnis, Gottes Sohn, Muß uns die Freiheit kommen’ (Through your imprisonment, Son of God, must our freedom come) which was sung with poise and honesty, only to be swept aside by the Jews’ feverish accusation, “Lässest du diesen los, so bist du des Kaisers Freund nicht”(If you release this man, then you are not Caesar’s friend). The widely arrayed massed voices seemed to fling the sound at Pilate from every nook and niche of the Cathedral, and if the ensemble was not always pristine, then the verisimilitude was almost terrifying, enhancing both the refinement of the Evangelist’s human dignity and the intensity of Pilate’s anguish.

The solo arias took us through a gamut from loyalty to betrayal, from hope to despair, from contentiousness to acceptance. Countertenor Hugh Cutting made us feel the rawness of Christ’s wounds and the bitterness of the “sin that binds him” in ‘Von den Stricken meiner Sünden’; Lucy Cronin’s bright soprano conveyed the steadfast devotion of ‘Ich folge dir gleichfalls’. The jagged rhythms of ‘Ach, mein Sinn’ truly tormented tenor Bradley Smith’s soul while Ben Davies’ dark bass and sensitive diction persuasively communicated the anguish of ‘Betrachte, meine Seele’. In ‘Erwäge, wie sein blutgefärbter Rücken’ (Ponder well how his back bloodstained), Guy Cutting’s lovely, expressive tenor was complemented by the winding triplets of the two violins, which seemed to embody both the wringing of hands and heart and the patterns of blood on Christ’s body.

Bass Tom Lowen’s confident ‘Eilt, ihr angefochtnen Seelen’ was vivified by the agile, running vocal line, the busy string accompaniment and the slicing interjections of the ‘tormented souls’. Jonathan Manson’s eloquent viola da gamba obbligato deepened the pathos of ‘Es ist vollbracht!’ (It is accomplished!) which countertenor Alexander Chance sang with discernment, switching from concentrated contemplation to dramatic immediacy with the sudden outburst, “Der Held aus Juda siegt mit Macht” (The hero from Judah triumphs in his might). Tenor Sam Jenkins was an assured soloist in ‘Mein Herz, in dem die ganze Welt’, while, after the piercing of the dead Christ’s side by the Roman soldier’s sword, Lucy Cox’s shining soprano, heightened by vivid instrumental dialogues, conveyed the almost ecstatic intensity of ‘Zerfließe, mein Herze, in Fluten der Zähren’ (Dissolve, my heart, in floods of tears).

These arias were given vivid character and drama by the instrumentalists led by violinist Bojan Čičic. Yu-Wei Hu’s and Jonathan Slade’s baroque flutes, the fine-grained oboes of Frances Norbury and Oonagh Lee, Rosie Moon’s energised double bass, Johann Löfving’s intricately rippling theorbo and Catriona McDermid’s agile bassoon were as much participants in the drama as were the singers with whom they conversed.

But, as always with Bach, it was through the chorales that the deepest emotional rivers ran. ‘Petrus, der nicht denkt zurück’ (Peter, who does not think back at all) had such strength and directness that our Evangelist closed his eyes to absorb its message. Unwavering pillars of faith gave ‘In meines Herzens Grunde’ (In the depths of my heart) nobility and stature, while ‘Er nahm alles wohl in acht’ (He thought carefully of everything) was consolingly tender. During ‘O hilf, Christe, Gottes Sohn’ (Oh help us, Christ, God’s Son) the voices reached out from the choir stalls towards the Evangelist, as if imploring him to fill the unfillable space left by Christ’s Crucifixion. And, finally, we reached ‘Ach Herr, lass dein lieb Engelein’ (Ah Lord, let your dear angels), slow and sombre at first, building with gradually accruing intensity – individual faces framed by the camera, their mouthed words confirming the collective sentiment – towards the release and redemption of the final glorious declaration: “Herr Jesu Christ, erhöre mich, Ich will dich preisen ewiglich!” Lord Jesus Christ, hear me, I shall praise you eternally!

Oxford Bach Soloists’ Easter Festival is available on demand until 30th April.

https://www.oxfordbachsoloists.com/easter-festival-2021/

Claire Seymour

Bach: St John Passion BWV245

Evangelist – Nick Pritchard, Christ – Peter Harvey, Pilate – Alex Ashworth, Sopranos (Lucy Cronin, Lucy Cox, Gwen Martin), Altos (Hugh Cutting, Alexander Chance), Tenors (Bradley Smith, Guy Cutting, Sam Jenkins), Basses (Alex Ashworth, Ben Davies, Tom Lowen); Thomas Guthrie (director), Tom Hammond Davies (conductor), the instrumentalists of Oxford Bach Soloists.

Recorded at Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford; first streamed on 2nd April 2021.

ABOVE: Peter Harvey (Christus)