‘Pyrotechnics’, noun (plural): a public show of fireworks; a show of great skill, especially by a musician or someone giving a speech.

William Towers’ recent recording of Handel arias, with the Armonico Consort directed by Christopher Monks, is aptly named, although – while there are vocal fireworks – it is Towers’ vocal discipline, beguiling tone and ability to shape and sustain a musical line which are most striking and impressive. The majority of the eleven arias presented are examples of the slow, noble type, in which profound human emotions are expressed in music of sublime beauty and stirring eloquence. Many of those selected are well-known favourites – ‘Ombra ma fù’ (Xerxes), ‘Dove sei’ (Rodelinda), ‘Cara sposa’ (Rinaldo), ‘Ombra cara’ (Radamisto) – but there are some less familiar choices too, such as ‘Se possono tanto due luci vezzose’ sung by the eponymous protagonist of Poro, re dell’Indie,which Towers explains was his first Handel role. He adds that, although the opportunity arose some time ago, he delayed making this recording until ‘I had performed a significant number of [Handel’s] operas, and to choose repertoire for a recording that I knew and loved; that I had fully lived with’.

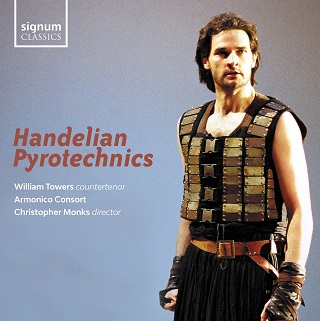

I’ve seen Towers in Handelian roles on two occasions: in the title role of English Touring Opera’s Radamisto at Snape Maltings in November 2018 and, a year later, in a smaller role as the Christian Magician in Glyndebourne Touring Opera’s Rinaldo. What struck me on hearing this disc is just how attractive his countertenor is, the fullness of body and colour enhanced by his even projection and control. In this sequence of arias, he creates credible characters that win our sympathy and understanding, and captures a range of emotions from loneliness to jealousy, loss, courage, desire. His diction is idiomatic and crisp, and he uses the Italian text to deepen the innate lyricism of the line.

Towers is accompanied by a slimmed-down Armonico Consort comprising, in most of the arias, just four strings and theorbo with Christopher Monks directing sensitively and imaginatively from the harpsichord. The one-to-a-part lines are expressive in ‘Ombra ma fù’: one can hear the individual voices within the pulsing crotchets, while leader Kelly McCusker has freedom to inject her own expressive nuances – there’s a lovely accented ‘sob’ or two. The result is both intimate and sensuous. Toby Carr’s theorbo is prominent, rippling across beats and bars, and propelling what is a rather languorous tempo. Handel’s marking is Larghetto, and there should surely be rather more of a gently sway to entrance the ear, and convey Serse’s own infatuation? Soulful rather than sleepy? Towers’ entrance is clarion, and he doesn’t waver an iota through the first long-held note, using his strength and focus to make what is difficult seem effortless. This aria has been transposed down, but it still encompasses a wide range and Towers is as warm at the bottom as he is sweet at the top. The ornamentation is elegant and expertly rendered: expressive appoggiaturas and a neat trill coax meaning from Serse’s praise, “Soave più”.

Rinaldo’s ‘Cara sposa, amante cara’ is prefaced by soulful ‘weeping’ counterpoint in the upper strings, the evocation of the hero’s sorrow and suffering after Almirena’s abduction by the sorceress enhanced by the sparseness of the texture. When the theorbo enters, Carr is more restrained, allowing the eloquence of Poppy Walshaw’s cello motifs to sing clearly. The B section is brief but brisk, incisive but never heavy. Rinaldo’s defiance burns as the final cadence plunges low, before the extravagant but never inappropriately ornamented da capo. Bertarido’s aria of longing for Rodelina, ‘Dove sei, amato’, is likewise gracefully sculpted, though the absence of the preceding recitative, which would have set the aria in context, is disappointing. Instead, Towers’ opening note comes from nowhere, and is held for fifteen seconds, which does seem rather excessive.

From Radamisto we have ‘Qual nave smarrita’, which benefits from plaintive reedy oboes (Geoff Coates and Jane Downer), in which the protagonist bids farewell to his beloved Zenobia. Towers squeezes every ounce of sadness from the final cadence of the B section, “misero cor”, Radamisto’s ‘wretched heart’ truly wrung through the sweetly descending scale which Towers adds. The fervour of ‘Ombra cara’, in which the hero promises to avenge his wife’s death, is enhanced by Siona Spillett’s characterful bassoon playing, although a bit more weight feels needed in the strings. Towers sings with earnestness and strength, communicating Radamisto’s belief that he will be reunited with Zenobia in the afterlife.

Poro’s ‘So possono tanto’ has a bouncier spring in its step. This opera, which dramatises Alexander the Great’s invasion and conquests in India in 327-6 BC, opened Handel’s second season (1730-31) at the Royal Academic of Music and marked Senesino’s triumphant return to the London stage. In this aria, the Indian king Poro, concerned by his wife Cleophide’s visit to the conquering Alexander, sings of the tortures of jealousy, which should invoke pity, not scorn. Towers’ ornamentation of the da capo reprise is judicious; eloquently decorative while still maintaining the essential simplicity of the line. When that line sinks low, the plushness of his countertenor and his expressive use of vibrato give his voice a quite contralto-like timbre.

Guilio Cesare was another of Senesino’s great roles, and Towers and Monks offer two arias from the opera. It’s good to hear the accompanied recitative that precedes ‘Aure, deh, per pietà’, in which Cesare, saved from drowning by propitious Fate, tells of his escape and then laments his loneliness. The instrumental introduction is characterised by persuasive dialogues between the high and low strings and sequences that never sound workaday, and eases effectively into Tower’s flexible recitative in which he communicates Cesare’s weariness, confusion and despair. The broadening of the final phrase, “Solo in quest’erme arene/ Al monarca del mondo errar conviene?” (Alone on these desert sands/ The ruler of the world must wander?), adds to the weight of the falling appoggiaturas and conveys Cesare’s pained exhaustion, while Towers takes “monarca del mondo” high, creating an octave plunge which is expressive of the pathos of the king’s fall. There’s the slightest of tuning issues as Towers turns the corner into the aria, which mars what is otherwise a lovely messa di voce, but the aria has a charming lilt and he makes much of the alliterative text, conveying the deep earnestness of Cesare’s prayer: “Per dar conforto, oh Dio! al mio dolor./ Dite, dov’è, che fa I’dolo del mio sen,/ L’amato e dolce ben di questo cor?” (To give comfort, O God! to my grief, tell me, where is the idol of my breast, the beloved and sweet goodness of this heart?)

From Act 2 comes ‘Al lampo dell’armi’, Cesare’s display of heroic confidence, and the strings duly race insouciantly through their semi-quavers, leaps and accents imitating nonchalant shrugs of self-belief – though this is one aria in which a bigger string section, in particular a stronger bass line, would give more punch. Towers is similarly untroubled by the aria’s technical demands and surges cleanly and relaxedly through the circling runs with agility and accuracy. Orlando’s ‘Cielo! Se tu il consenti’ isn’t the most obvious choice of aria, but there’s no doubting the disintegration of the insanely jealous protagonist’s personality as Towers sails through the rapid triplets with remarkable control, evenness and stamina. When the line loops downwards he crosses the registers seamlessly, and the extensive ornamentation of the da capo is both imaginative and convincing. Again, though, the accompaniment needs to make a bit more impact.

Scene 1 of the final act of Agrippina opens with Ottone’s exclamation of love for Poppea, ‘Tacerò, purchè fedele’. This is an old-fashioned aria accompanied by only bass and continuo, and Walshaw’s ground-like bass line is lithe and characterful. I’d like a little more rhythmic definition in the vocal line – semiquavers, in imitation of the cello, have a tendency to slip into triplets – but as throughout this disc, Towers’ crafting of the ‘drama’ conveyed by the arching musical structure is sure.

After all the sorrows and suffering, the disc ends on a more buoyant note with another of Senesino’s ‘hits’, ‘Dopo l’orrore’ from Ottone, re di Germania. Here, jealousy inspires admiration, as Ottone likens the soothing of Teofane’s troubles and the restoration of love’s assurance to the sun’s brightening of a stormy sky, made more delightful by the preceding gloom. It’s an uplifting conclusion to an accomplished and attractive disc.

Claire Seymour

William Towers (countertenor), Armonico Consort, Christopher Monks (director)

Handel – ‘Ombra mai fù’ (Serse), ‘Se possono tanto due luci vezzose’ (Poro), ‘Al lampo dell’armi (Giulio Cesare), ‘Dall’ondoso periglio – Aure, deh, per pietà (Giulio Cesare), ‘Cara sposa’ (Rinaldo), ‘Cielo! Se tu il consenti’ (Orlando), ‘Dove sei, amato bene?’ (Rodelinda), ‘Qual nave smarrita’ (Radamisto), ‘Ombra cara di mia sposa (Radamisto), ‘Tacerò, purchè fedele’ (Agrippina), ‘Dopo l’orrore’ (Agrippina)

SIGCD658 [60:52]

ABOVE: William Towers as Radamisto, English Touring Opera 2018 © Richard Hubert Smith