I have written with enthusiasm about numerous recordings from the Rossini festival that is held each summer – well, except 2020 – in Wildbad (in Germany’s Black Forest region). One opera was by Bellini (Bianca e Gernando – see my review here), and most of the others were by Rossini, including Adelaide di Borgogno and Sigismondo (which I reviewed, together, here), Zelmira (here), Edoardo e Cristina (here), Moïse et Pharaon (here), and Aureliano in Palmira (here). Most recently, I reviewed the world-premiere recording of Meyerbeer’s early (he was 26) but already highly accomplished and entertaining Romilda e Costanza, which featured a fine international cast, headed by Patrick Kabongo, a vibrant and stylish young high tenor from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. (See my review at the wide-ranging arts blog The Arts Fuse, edited by Bill Marx, longtime faculty member of Boston University’s writing program.)

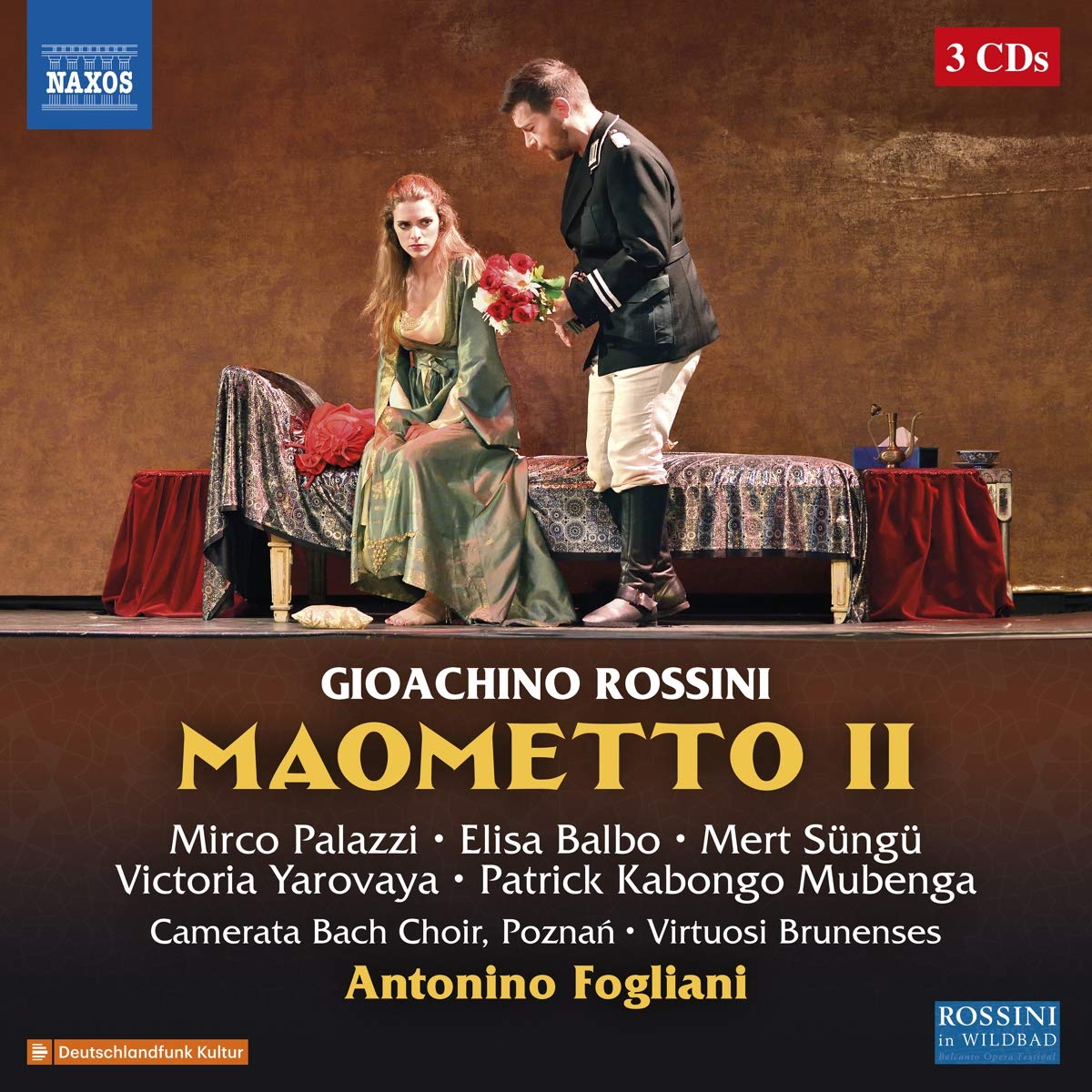

The present recording, released somewhat belatedly, blends multiple performances (from July 2017) of Rossini’s important opera Maometto II. This was the next-to-last in a series of unusually imaginative and often expansively structured operas that he wrote during the years he spent running the opera theater in Naples.

Maometto II was first performed in 1820. It deals with a territorial struggle between Venice and the Ottoman Empire in the fifteenth century. The title character is the renowned Sultan Mehmed II. The librettist Italianized the sultan’s name, following the custom in Italian libretti at the time. (In Donizetti, Sir Walter Scott’s Lucy becomes Lucia; in Verdi, Alfredo is a Parisian whose actual name is presumably Alfred.)

As usual in opera, the historical “givens” ended up being subordinated to various plots involving requited and unrequited love. Still, the result is very effective and moving. And, with its coloratura demands, it gives strong, flexible singers a wild ride. (It also would give weaker singers a wilder ride, but that’s not often the case here.)

In 1826, Rossini heavily reworked Maometto II for the Paris Opéra. He and his librettist shifted the opera’s location, changed the nationality of the Europeans from Venetian to Greek, and changed the title to Le Siège de Corinth. They thereby evoked more explicitly certain current-day events to which Maometto II had already alluded: the war that the Greeks were fighting throughout the 1820s for independence from the Ottoman Turks. The reworked opera later got (re)translated back into Italian as L’assedio di Corinto.

Maometto II is often praised for its mammoth Terzettone (“big fat trio”) in Act 1, during which three of the four main characters (Anna, Calbo, and Paolo), after singing together for some time, hear loud cannon shots and run outdoors, where the musical number continues with several other extended sections, not least a gorgeous prayer for Anna and chorus, the famous “Giusto ciel, in tal periglio.” Also astonishing is the twenty-minute closing scene, in which Anna ends up committing suicide (Maometto’s forces having triumphed). Rossini, when revising Maometto II for Venice in late 1822 (that is, before rewriting it more heavily for Paris), replaced this long scene with a more conventional final aria borrowed from his own La donna del lago. The Venice version has a happy ending (for the opera’s Italian characters): the Turks are defeated, and Anna marries Calbo. Rossini made many other changes, such as adding an overture: the original (Naples) version jumps right into the first scene.

The Terzettone and long, tragic Act 2 finale are indeed wonderfully rich. But my favorite swath of music is the equally long finale to Act 1, which contains several extended sections in which the four main characters (the three mentioned above, plus Maometto) sing together or echo each other’s melodic statements, in ways that anticipate such memorable moments as the Sextet in the Act 2 finale of Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor and the unaccompanied quartet in Act 2 of Verdi’s Luisa Miller.

The new recording of Maometto II is the sixth or so to have been released on CD. (Some are out of print, but used copies may be found.) An Avie release uses singers who are little-known, light-toned, and flexible (and all, or mostly, British). It was recorded in an unstaged performance, I believe; applause follows many numbers. Bel-canto specialist David Parry keeps things moving forward while also shaping phrases intelligently.

Even more gratifying is a Philips recording conducted by Claudio Scimone, with June Anderson, Margarita Zimmerman, Chris Merritt, and Samuel Ramey, who were singing splendidly at that point in their careers (1983). The current re-release lacks a libretto.

Naxos already released a recording of Maometto II some fifteen years ago. It is perhaps the only CD set to use the 1822 Venice version. That first Naxos release was conducted by Brad Cohen and was made in 2002, at the same “Rossini in Wildbad” festival as the new recording. In the May/June 2005 issue of American Record Guide, Michael Mark found the two main male singers inadequate.

Naxos’s new recording uses (like the Avie) the original 1820 version as restored in the Bärenreiter critical edition. The booklet contains a helpful synopsis (with track numbers) and an insightful essay about the work’s complicated history. One confusing typo: the word “explore” appears as “explode”!

Naxos provides online an Italian-only libretto, with the track numbers printed helpfully in red. Still, I long for the days when a recording of an important and little-known opera would come with an English translation. Perhaps I’ll try to find the old Scimone/Philips recording in a library, or the Avie release, and photocopy its bilingual libretto.

The new Naxos release is spirited and clear, much like the Avie: in neither are there heavy broadenings of the tempo. I felt the extra excitement of an onstage performance, thanks in part to perceptible but not annoying sounds of people moving around, unsheathing swords, etc. (The beginning of each track can be enjoyed here. The entire recording is available on YouTube, Spotify, Naxos Music Library, and other streaming services.) The mostly youngish singers handle the tricky coloratura well, though rarely with the total precision that many of us old folks got accustomed to during what now looks like the golden half-century of studio-recorded bel canto opera (ca. 1955-2005). The most stylish of the present soloists is Russian mezzo Victoria Yarovaya (whom I admired in two previous Rossini operas from the Wildbad festival), in the important trouser role of Calbo–the Venetian general whom Anna grows to love.

The recording’s main tenor, Mert Süngü, sings the role of Paolo Erisso, Anna’s devoted father. Süngü is from Turkey and began his training there but completed it in Bologna. He likes to take high notes at full voice, despite everything we know about vocal practice around 1820. Fortunately, his voice is clean and firm throughout its range. The recording’s other tenor, the aforementioned Patrick Kabongo (at that point singing under the name Patrick Kabongo Mubenga), sings two small roles well: Condulmiero and Selimo. He apparently got his training mainly in Brussels.

Bass Mirco Palazzi holds one unwritten high note almost forever, and not beautifully (whereas Süngü’s long high notes are a treat to hear). Like several other cast members, Palazzi has an incipient wobble on long notes and tends to go a bit sharp when excited. Fortunately, for all of them, the wobbles become less annoying or even vanish as the performance moves along and the voices warm up.

By contrast, in the Philips recording (1983), made in the studio, all the vocalists sound fully in control from beginning to end yet also rich and full. One advantage of studio recording is that the arias and ensembles can be recorded in any sequence and even at a time of day that suits a particular singer. And, of course, passages of any length (including short “patches”) can be recorded multiple times until everyone is satisfied.

Orchestra and chorus in the new recording show much spirit and good ensemble under conductor Fogliani. The solo wind players are superb. (The work contains several notable and exposed passages for clarinet.) The editors seem to have trimmed applause to a minimum, for which I was grateful.

I highly recommend either this recording or the Avie. Still, the 35-year-old Philips recording consistently offers vocalism that manages to be just that bit stronger: at once precise and luxurious. The orchestral sound on Philips is warmer and more resonant than on the new recording or the Avie, and Scimone often varies the tempo for expressive effect, in ways that make the work feel more weighty and meaningful.

Dynamic has made available a DVD of a performance of the Venice version (i.e., the same version done on Naxos’s 2002 recording) with Lorenzo Regazza, Carmen Giannattasio, Maxim Mironov, and other highly capable singers, again under Scimone. It was much praised here at Opera Today.

In short, one of Rossini’s most daring and richly endowed works is clearly finding its way back into our musical life. It is a treasure box well worth opening!

Ralph P. Locke[*]

Elisa Balbo (Anna Erisso), Victoria Yarovaya (Calbo), Mert Süngü (Paolo Erisso), Mirco Palazzi (Maometto II), and introducing Patrick Kabongo Mubenga (Condulmiero, Selimo).

Virtuosi Brunenses and Poznan Camerata Bach Choir, cond. Antonino Fogliani.

Naxos 8.660444-46 [2 CDs] 120 minutes

[*]Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback, and the second is also available as an e-book. The present review is a lightly revised version of one that first appeared in American Record Guide and is used here by kind permission. Ralph Locke contributes to the online arts-magazines NewYorkArts.net, OperaToday.com, ArtsFuse.org, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer, and Musicology Now, the blog of the American Musicological Society.