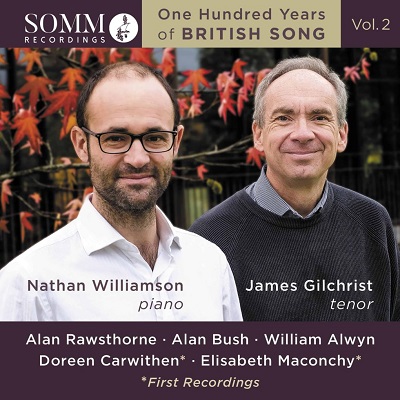

In October 2020 tenor James Gilchrist and pianist Nathan Williamson opened their three-volume survey of the less well-traversed byways of the British song repertoire, One Hundred Years of British Song, with a disc focusing on composers who were born in the late nineteenth century and experienced the horrors and upheaval of the First World War and its aftermath: Gustav Holst, Rebecca Clarke, Ivor Gurney and Frank Bridge.

For the second disc of the series, the duo have turned to five composers whose song-writing years overlap with the Second World War. William Alwyn, Alan Bush, Alan Rawsthorne and Elizabeth Maconchy were all born in the first decade of the twentieth century. Doreen Carwithen, who was born in 1922, began her studies at the Royal Academy of Music in 1941. Alwyn had been appointed Professor of Composition at the Royal Academy of Music in 1926 when he was just 21 years old, a position he retained for almost thirty years, and Carwithen entered his harmony class. Twenty years later they set up home together; in 1975 she became his second wife, adopting the name Mary Alwyn.

Gilchrist and Williamson open their recital with William Alwyn’s late song-cycle, A Leave Taking (1978), which was composed for the tenor Anthony Rolfe-Johnson, who had taken the role of the Gamekeeper in the composer’s 1976 opera, Miss Julie, and who premiered the seven-song cycle with the pianist David Willison at Blythburgh, Suffolk in 1979. Alwyn selected texts from Poems Dramatic and Lyrical (1893) by John Byrne Leicester Warren, the third and last Baron de Tabley (1835-95) – poet, numismatist, botanist and ornithologist.

Reading through Lord de Tabley’s poems, I was struck by their erudition, complexity and density – they seem to have much in common with the seventeenth-century poetry of Jonson and Donne – but also by the poet’s minute and veracious observation of natural phenomena. From the lyricism of ‘The Pilgrim Cranes’ – “The clouds are herded pale and rolling slow./ One flower is withered in the warm wind’s mouth” – and ‘Daffodils’, whose amber petals are “Sheeting the floors of April”, to the terrible detail of ‘Study of a Spider’, whose “winding sheets are gray and fell,/ Imprisoning with nets of hell/ The lovely births that winnow by,/ Winged sisters of the rainbow sky” – the poetic imagery draws richly upon the visible natural world. But, despite the beauty and creativity of earth and sky, celebrated in ‘The Ocean Wood’ – now silent, shady and undisturbed, but in which “Soon will the ripple move again:/ Soon will the shore-lark flute its song” – the prevailing sentiment of the poems is one of pessimism, even despair.

Alwyn responds sensitively and precisely to the poetry’s lyrical sensibility and potent imagery. The piano’s sparse, cool etchings at the opening of ‘The Pilgrim Cranes’ capture the serenity of the birds’ sky-flight, but Alwyn does not neglect the sound and sense at word-level, expanding the rather declamatory vocal line with the picture of clouds “rolling slow” and pushing the tenor high to capture the emotion in the gentle waters’ rhyming momentum, “always flow” – gestures which James Gilchrist exploits with characteristically judicious emphasis and colouring. Alwyn was until more recent decades most celebrated for his film scores, and one senses this experience as his music conveys the passing of time – harmony, melody and textures swelling richly with the vision of a flaming sunset which descends beyond the dome-like mountains. The rapture quickly drains, however, and the final two lines retreat into loneliness, as the poet-speaker urges his “old anguish” to sleep, “and cease/ To listen for a step that will not come.”

Such closing gestures become a repeating trope. Despite the awakening of sweet sounds in the titular ocean wood, “all the ships that ever sail/ Will bring no comfort home to me.” The ‘Two Old Kings’, “great and wise”, are left only with heroic hearts as they tread their “lonely way”. And, even when luck and love at last seem the poet’s lot, in the brief and boisterous ‘Fortune’s Wheel’ – Gilchrist and Williamson really bring the ballad-narrative to life – there’s no escaping betrayal and grief: abandoned by his lady in favour of the poet’s friend, “My cask ran sour, my horse went lame,/ So along in the cold I end”. Alwyn rather overdoes the misery here, repeating “alone”, twice, a sort of visceral groan, and then restating the whole final line as the piano plunges deep and dark.

But, despite the preponderant gloomy hopelessness, the songs do not lack an inner life and feeling. Against the piano’s lovely sea-lilt at the start of ‘The Ocean Wood’, Gilchrist’s tenor is leisurely and infused with both a blush of colour and an intimation of enchantment, as the birds ride the “gleaming bands of sunset”, and the rock-dove and curlew sing and soar. The forward momentum of new growth is enhanced by the piano’s high chiming intervals, and the joys and pains of the Romantic sublime are not forgotten when silence consumes the sweet song and pain is left unassuaged in the voice’s closing dissonance. Gilchrist renders the horrors of the spider’s murderous mischief with a precious care for the text and mounting vocal intensity, as the piano pounds out a gothic tumult which climaxes with the ghastly image of the “Toper, whose lonely feasting chair/ Sways in inhospitable air.” There is a sense of catharsis in the chilling unisons of the closing image of retribution, as the poet-speaker breaks “the toils around thy head/ And from their gibbets take thy dead.” Here, Gilchrist and Williamson really make the flesh creep!

Moreover, there is passion and dynamism at times, most sensuously in ‘Daffodils’, in which the fusion of the scent and touch of petals and the beloved’s “rich cheek” inspires hope and renewal, and music of restless passion; Williamson impresses in mastering Alwyn’s complex piano writing, and Gilchrist equals him in shaping and projecting the vocal line above the instrumental rapture. The quiet close – “I cannot think she never will be won” – is calm and assured. Gilchrist is an eloquent communicator of the Old Kings’ nostalgia, while Williamson conjures the strength of spirit that permits them to march on in the morning light, “as soldiers laurelled on our brows”, after one “last carouse”. The gently throbbing harmonies of the piano introduction to the eponymous final song have a beautiful wistfulness, and the more expansive melodism of the vocal line allows Gilchrist to use the sweet warmth of his tenor, and his discerning articulation of the text, to communicate the poem’s honesty and resignation.

The songs which follow, from Prison Cycle by Alan Bush and Alan Rawsthorne, do not lift the sober mood. The composers’ shared socio-political interests saw Rawsthorne participate in some of the Labour Party pageants arranged by Bush during the 1930s and 1940s. One such was the pageant Music and the People (to which Vaughan Williams, Rubbra and Tippett also contributed), in April 1939. The two composers selected poems from Schwalbenbuch (The Swallow Book) by Ernst Toller, a German Jewish left-wing poet, which were written while Toller was serving a five-year prison sentence for taking part in the 1919 Munich Revolution. He committed suicide a month after Prison Cycle was first performed.

The introduction, interlude and epilogue set the brief poem ‘Sechs Schritte her’, which describes the poet-prisoner’s aimless steps, back and forwards, across his cell. It serves as a sort of ritornello, with Rawsthorne’s interlude echoing some of the motifs of Bush’s framing settings. Interleaved are ‘Die Dinge’ (Bush), which conveys the poet’s affectionately familiarity with the ‘things’, tables, bars, midges, in his cell; and, ‘Über mir’ (Rawsthorne), in which a pair of nesting swallows captivates the poet, until the prison guards brutally intervene.

Bush interprets the “Six steps forward, six steps back” quite literally and Williamson’s heavy tread has a claustrophobic weight; the rhythmic rigidity is not alleviated by the voice, though Gilchrist imbues the repetition of “Ohne Sinn” (without purpose) with the subtlest of elegiac tints. Rawsthorne’s interlude seems to push forward more forcefully; but, while the harmonies have greater consonance, the intervallic emotiveness of “Ohne Sinn” more openly conveys the prisoner’s despair.

‘Dir Dinge’ is surprisingly Schumann-esque, though perhaps not so surprising after all, given that the text communicates a Romantic sensitivity to the surrounding world, however confined. Gilchrist’s tenor is initially relaxed, as the prisoner realises that the objects around him are not hostile but inviting, and the quiet piano chords that accompany the second stanza suggest wonder and freshness, as the world is discovered anew. Even the barred windows, conjured by the piano’s restless circling, inspire strength as Gilchrist presses forward towards the transcending vision of the closing stanza in which the poet builds a cloud-paradise for those who are shot beyond his barred windows, the rhythmic displacements and cross-pulses creating a slightly delirious intensity.

Rawsthorne’s ‘Über mir’ has a similar Romantic quality, the piano’s triple-time lilt underpinning the mesmerising vision of the little pair of swallows that sway upon the half-opened window of the prison cell, and anticipating the bird’s wild, waltz-like dance, “Tantz! Tantz!” Rawsthorne does not dramatise the guards’ violence; it is left to the bleak pounding of the final refrain – and the anguished strain in Gilchrist’s vocal line – to convey the anger and despair. “Ohne Sinn” falls; first a tone, then a minor sixth, made more bitter by the piano’s intruding dissonant harmony. There is no consolation.

It’s not until we reach the middle of the disc that there is any real note of joy and humour, in Rawsthorne’s 1943 settings of two poems by the Jacobean poet-playwright John Fletcher. Or, rather, one of the settings. Drawn from Fletcher’s The Captain – where it serves as the courtesan Lelia’s seduction song which temporarily persuades the young courtier, Julio, to marry her – Rawsthorne’s ‘Away, delights!’ has a Finzi-esque melancholic beauty and underlying contrapuntal grounding. Its bittersweet, fluid lyricism contrasts with the rumbustiousness of ‘God Lyaeus, ever young’, with its bravura rhetoric – “Let a river run with wine” – and essential grace: a drinking song for the elegant and urbane.

In his detailed and eloquent booklet article, Williamson suggest that Maconchy’s Three Donne Songs are ‘substantial, ambitious songs, imbued with a genuine sense of drama by an assured composer at the height of her powers’. It is claimed that this is the first recording of these songs, composed between 1961-65 and gathered together for publication in 1966, which present Donne’s addresses to three ‘deities’: ‘A Hymn to God the Father’, ‘A Hymn to Christ’, ‘The Sun Rising’. This claim is true, in part; but, in fact James Geer and Ronald Woodley pipped Gilchrist and Williamson to the post by including ‘A Hymn to God the Father’ in their SOMM release, Dreams Melting, in March this year. Moreover, Maconchy’s 1931 Two Motets for unaccompanied double chorus set the first two texts: I’m not able to access scores and scrutinise/compare, but it wouldn’t be unimaginable, given the apparent contrapuntal underpinning, that the later songs draw on this earlier material.

I have to say that I found Maconchy’s setting of ‘Hymn to the Father’ rather ‘dry’ – though it does showcase the pristine clarity of Gilchrist’s and Williamson’s expression – in contrast to the irony and wit of Donne’s poem. For, the latter juxtaposes a routine deathbed confession with intimations of subversion, the short line concluding each stanza, “For I have more”, “I fear no more”, seeming to suggest that, despite Donne’s confessional declarations, the poet is aware that his greatest sin is in loving his wife, Anne More – the niece of Lord Egerton to whom Donne was secretary, and whom he secretly, resulting in his imprisonment and dismissal – more passionately than his God. ‘A Hymn to Christ’ is more impassioned and draws burning commitment from the duo, the piano lines taut and insistent, Gilchrist’s tenor at times inflamed, elsewhere fluently articulate, and at the close passionately persuasive. ‘The Sun Rising’ is explosive, both tenor and piano soaring high, plummeting low, as unpredictable as Donne’s metre. The poem’s opening lines, “Busy old fool, unruly Sun,/ Why dost thou thus,/ Through windows, and through curtains, call on us?”, seem to sum up the confidence, energy and sheer bravado of the poem and song, in which Donne – echoing Galileo’s heliocentrism, hyperbolic, but also rooted in real human feeling – places himself and his lover at the centre of the universe. Donne issues a challenge to the rising sun which demands that the lovers part at dawn; Maconchy tests her performers, and Gilchrist and Williamson summon a human and life-giving energy to meet the musical challenges.

Following such braggadocio, the seven miniatures by Doreen Carwithen that conclude the disc might seem underwhelming, but Williamson suggests that they are ‘real gems revealing the seeds of a truly imaginative and expressive musical personality’, and it’s impossible to disagree.

In the late 1940s Carwithen’s compositional career blossomed: her Mansfield-inspired overture One Damn Thing After Another received its premiere at Covent Garden, conducted by Sir Adrian Boult. And, in the same year, Carwithen became the first student to be selected from the Royal Academy to join an apprenticeship scheme set up by J. Arthur Rank to train young composers in the writing of film music. Over the next fifteen or so years she wrote scores for some 35 films. In 1952, her overture, Bishop Rock, opened the Birmingham Proms, and that summer her Concerto for Piano and Strings premiered at the Proms. She was the sole female composer to have a work performed in that Proms season. But, unable to find a publisher interested in promoting music composed by a woman, and working as Alwyn’s secretary and amanuensis, she put her own compositions on hold and only after her husband’s death in 1985 did she resume her creative work.

The seven songs recorded here, for the first time, are a real joy. ‘Serenade’ sets the octet of Sir Philip Sidney’s sonnet, ‘My true love hath my heart and I have his’, from Arcadia, the pastoral narrative which Sidney composed c.1580. The speaker is a shepherdess, pledging her love for her betrothed, a shepherd who rests in her lap. Carwithen omits the complex conceits of the concluding sestet, and the piano’s harp-like celestial strumming captures the initial, straightforward expression of unifying human love: Gilchrist’s softly ecstatic restatement of the opening line captures this completely and consolingly. Three Song to Poems by Walter de la Mare release the tender expressiveness of Gilchrist’s tenor: a swan whose mirrored image floats beneath the willow tree (‘Noon’), “Seven Sweet Notes/ In the moonlight pale” (‘Echo’), witches who “With a whoop and a flutter … swing and sway/ And surge pell-mell down the milky way” (‘The Ride-by-Nights’) – each moment and sentiment captures the listener’s ear and imagination. Williamson’s piano is delicately affecting, the gestures and harmonies pentatonic, pastoral and perky, by turn. Following the direct communicativeness of ‘Clear Had the Day Been’ (Michael Drayton), the magical renewal of ‘Slow Spring’ (Katharine Tynan) allows Gilchrist to use his melting head voice to touching and reverential effect.

‘Echo (Who Called?)’, another de la Mare setting, closes the recital and reduces word and music to sound – a strange sound which unsettles and reminds the poet-speaker of his unfathomable place in a wider universe. In Gilchrist’s and Williamson’s hands it becomes a beautiful yet tremulous microcosm of all that has gone before.

Claire Seymour

James Gilchrist (tenor), Nathan Williamson (piano)

William Alwyn – A Leave-Taking; Alan Bush/Alan Rawsthorne: Prison Cycle; Alan Rawsthorne –Two Songs to Poems of John Fletcher; Elizabeth Maconchy – Three Donne Songs; Doreen Carwithen – ‘Serenade’, ‘Noon’, ‘Echo (Seven Sweet Notes)’, ‘The Ride-by-Nights’, ‘Clear Had the Day Been’, ‘Slow Spring’, Echo (Who Called?)’

SOMMCD 0636 [63:37]