When Gabriela Preissová’s play, Její pastorkyňa (Her Stepdaughter), was produced for the first time, on 9th November 1890 at the National Theatre in Prague, it provoked a fierce debate between the advocates and opponents of realism, with the play’s critics complaining that, ‘Everything in it is covered by the frost of baseness, vulgarity, foolishness and contemptibility …’ The director of the National Theatre was steadfast in his defence of the play – set in a contemporary Moravian village and drawn from two real-life incidents which had been reported in a local newspaper – and Preissová is now recognized as one of the first Czech naturalist dramatists, even if the controversy led the then 28-year-old playwright to give up writing drama and turn to novels.

Preissová’s play persists in our immediate cultural consciousness largely because it was adapted by Leoš Janáček for his ‘break-through’ opera Jenůfa, which premiered at the National Theatre in Brno on 21st January 1904. This new production at Covent Garden – the first at the ROH for twenty years, which was postponed in spring 2020 and is latest in the House’s current series of Janáček operas – suggests that the ‘realism debate’, in its various manifestations, is not dead yet. In an interview with dramaturg Yvonne Gebauer, the director Claus Guth seems to suggest that historical realism precludes universality – that as we watch events, relationships and conflicts unfold between characters whom we recognise as situated in a particular time and place, we view such events as a ‘curious tale from the distant past’.

Guth does goes on to point out that ‘works like these’ are not set ‘merely in a (historical) village context’ and do not ‘function exclusively within that realistic framework’. And, in opera isn’t it essentially the music that knocks down the walls between past and present, between different cultures and social mores? I’m not in any way suggesting that operas such as Jenůfa (or any other dramatic work of any genre) that have a distinct temporal and geographic setting must be presented as a BBC-drama aspic-preserved period piece. And, indeed, Janáček’s own excisions cut about one third of the play, the village periphery suffering most, though not as much as in Káťa Kabanová. Only, it seems important to remember that the tragedy does not take place in a moral vacuum, and that very particular social and religious mores, and economic structures – the sincere and severe religious faith of the villagers, the domination of the village by its central mill – as well as local customs such as the return of the troops and the ritual preparations for a wedding – create a milieu which is not wholly unconnected from the characters’ actions and the consequences of their choices.

Guth’s production communicates powerfully and stirs heart-wrenching emotions – though his soloists have to overcome the hyper-symbolic burden imposed by the director to achieve this. There’s no doubting that, as Guth observes, in this opera we may recognise aspects of ourselves and our own lives: the repeating patterns of inescapable family history; moral codes which prevail, however insistent our resistance. Jenůfa is both real and universal. Guth, however, doesn’t seem to trust the audience to appreciate this, claiming that he wants us ‘to realize the universality of the story – and making that transparently clear is our aim’. One wonders if he thus lacks faith in the score, too?

But, putting such reflections aside, Guth’s production does pack a potent – and prevailingly pessimistic, at least in the first two acts – punch. Initially, we peer at Jenůfa’s suffocating milieu through black shutter-slats, which seem reluctant to permit entry as the curtain rises judderingly. When we are granted a vision of the locale, it’s not a rural village or habitation that we encounter but an urban, Dickensian workhouse. Set designer Michael Levine disperses the millworkers around the perimeter of a huge central square, the border formed of iron bedsteads, babies’ bassinets, and bridal trousseaus.

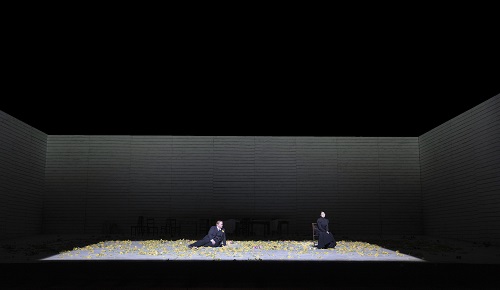

In Act 2, this world is turned psychologically ‘inside-out’: the bed-frames become the bars of the cages that imprison Jenůfa and her step-mother, the Kostelnička, as we step into the dark realms of their subconscious. The border is now fringed by seated, black-clad women, facing the white walls that confine both the real and unreal, the eyes – shrouded by handmaids’ cowls – seeing nothing and everything. A mattress-mound evokes the frozen landscape which conceals a murdered baby – at least until the frost thaws. Into this dreamworld stray a blood-stained child and a raven which perches on the corner of the cage. Of subtlety, there is little.

With the arrival of spring comes a splash of colour – a flower-strewn stage, vibrant native dresses – but the temperature remains chilly. The elders’ blessing of the soon-to-be-weds, the eager inspection of bride’s wedding chest, and the lukewarm rustic galops scarcely warm the spirit. But, the reference to a wider ‘context’ does at least offer some welcome explanation to questions which abstractions leave unanswered. We need to understand why the birth of a child would bring such shame; and, symbolic drudgery is an incomplete substitute for a mill-wheel – unceasing and as inescapable as time itself – which is both the centre of village life and also inextricably tied to the stream in which the Kostelnička will drown Jenůfa’s son. Context and consequence cannot be separated.

To compensate for the heavy-handed symbolism of Guth’s production, we have a superb cast of singers who enable us to live in the musical moment. Preissová’s play offers a psychologically complex Kostelnička: her personal history of an abusive marriage and her dominant position as the church warden within in a community whose moral attitudes are implicitly questioned, are made clear. Janáček’s succinctness robs the Kostelnička of some of that complexity, but Karita Mattila – twenty years after her interpretation of the title role on the Covent Garden stage – sings with such dramatic focus and expressive precision that we understand every atom of the Kostelnička’s motivation and madness.

In the play, the Kostelnička tries to rationalise her decision to murder the baby – Jenůfa will never agree to give up her child, drowning is swifter than diphtheria – but in the opera, it’s a split-decision choice, both impetuous and inevitable. Within a gripping arioso, when Mattila formulates the words that the Kostelnička imagines using to castigate Števa for his irresponsibility, as she throws the dead baby at his feet, it’s both tragic and terrifying: she has set herself on a path that she believes will spare her and Jenůfa the villagers’ approbation but her avowal that she will carry the child to God subverts the very ethics that she is seeking to uphold. Mattila makes sure we understand that reason has been absolutely ousted by moral blindness born of helplessness, despair and fear.

And, yet, in her alienation – isolated, insane, unredeemable – this Kostelnička is achingly vulnerable and ‘human’, almost Lear-like. She does not wish Jenůfa to suffer as she did; it’s only in Act 3 when Jenůfa refers to her explicitly as ‘step-mother’, that she understands that, in fact, the broken bloodline might have prevented such a tragic repetition. She begs Števa, whom she has previously condemned and spurned, to rescue her and her stepdaughter, and here Mattila captures the desperate lyricism of her declamatory pleading. James Farncombe’s lighting casts hideously looming shadows of Jenůfa’s prison: the message is clear – the Kostelnička has trapped herself. But, in fact, for all the bars and crows and handmaidens, it is Mattila’s sung monologue that really shows us that this Kostelnička has abstracted herself from ‘reality’.

The juxtaposition, in Act 2, between Mattila’s Kostelnička and Asmik Grigorian’s Jenůfa is one of the most moving aspects of the production. The latter’s whispered prayer to the Virgin has a wonderful calm, and the tenderness of Grigorian’s singing underlines her own moral stature and growth. In Act 1, Grigorian physically communicates all of Jenůfa’s inner tension and confusion, all the while exploiting the vocal lyricism: even as she seems not to understand that she stifles Števa’s desire for freedom, her frustration and anguish push her to taunt Laca, sealing her tragedy as he retaliates with the knife that mars her beauty. In the final act, Jenůfa’s spiritual development is writ large in the sensuous beauty of the Lithuanian’s soprano, conveying a generosity which transcends the cruelty of the villagers who cry, “Stone her!”

Nicky Spence’s Laca exudes a tense, and dangerous, energy, born of jealousy. It is not just when he is staring at Jenůfa, as his knife nicks the whip-handle he is carving, that envy speaks, but also when, in Act 1, Laca recalls the favouritism of his Grandmother Buryjovka who stroked the young Števa’s hair, praising it ‘as gold as the sun’. When taunting Jenůfa with Steva’s boast that the mill girls are all smiling, Laca’s emotional misery seems almost rapturous. But, later, the repressed passion blooms with a loving sincerity, the futility of which only deepens the anguish.

David Stout’s sure-voiced Foreman dynamically propels the action in Act 1, giving Laca the knife that will rob Jenůfa of the freshness that sustains Števa’s affection, praising her beauty and thus emphasising the cause of Laca’s frustration and fixation. Saimir Pirgu’s tenor rings with bright but shallow boastfulness, yet he brings some complexity to the feckless, vain Števa, and in his Act 2 confrontation with the Kostelnička his pain and fear are palpable. The secondary roles are all well sung, and it is particularly nice to see Jette Parker alumni Jacquelyn Stucker back at Covent Garden, as Karolka, rejecting Števa as a husband with a sure-sightedness that Jenůfa herself has previously lacked.

Conductor Henrik Nánási emphasises the lyrical qualities of the orchestral score, which frequently glows with a lovely warmth, but his tempi are sometimes a little broad for this listener, and as he milks the luxurious moments, he occasionally overwhelms the solo voices.

At the final reckoning, I found Guth’s production thought-provoking but frustrating. His trowel-full of symbols threatens to rob the drama of its humanity, though the singers work amazing wonders to bring back this emotional essence. And, in the final tableau Grigorian and Spence do summon warmth and hope, though it is as fragile as it is Hardy-esque. The ecstatic apotheosis of their love has to work very hard to counter Guth’s symbolic abstractions and to convince us that forgiveness and reconciliation really can transcend tragedy. The composer’s prose libretto may be derived from a play which adapts two events from real-life, but the true realism of the opera lies in the score’s delineation of character and feeling. In death there is renewal. I’m not sure that Guth made me entirely believe in this house of the living.

Claire Seymour

Leoš Janáček: Jenůfa

Jenůfa – Asmik Grigorian, Grandmother Buryjovka – Elena Zilio, Laca Klemeň – Nicky Spence, Jana –Yaritza Véliz, Stárek (Foreman at the Mill) – David Stout, Števa Buryja – Saimir Pirgu, Kostelnička Buryjovka –Karita Mattila, Barena – April Koyejo-Audiger, Herdswoman – Angela Simkin, Mayor – Jeremy White, Mayor’s Wife – Helene Schneiderman, Karolka – Jacquelyn Stucker, Tetka (Aunt) – Renata Skarelyte, Voices – Marianne Cotterill and Thomas Barnard, Dancers (Natacha Bisarre, Lauren Bridle, Henry Curtis, David Murley, Evie Poaros, Molly Shaw, Downie, David Stirrup, Aitor Viscarolasaga Lopez); Director – Claus Guth, Conductor – Henrik Nánási, Set designer – Michael Levine, Costume designer – Gesine Völlm, Lighting designer – James Farncombe, Choreographer – Teresa Rotemberg, Video –rocafilm.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Tuesday 28th September 2021.

ABOVE: Karita Mattila and Asmik Grigorian (c) ROH Tristram Kenton