Annibale Pio Fabri, known as ‘Ballino’, is not the best-known name amongst the singers who worked for Handel, yet on hearing him for the first time in 1729, Mrs Pendarves wrote described his voice as ‘sweet, clear and firm … he sings like a gentleman, without making faces, and his manner is particularly agreeable; he is the greatest master of musick that ever sang upon the stage’. For his two seasons in London, Handel both wrote him new roles and adapted existing ones, but Fabri also worked with a wide variety of European composers. There was a chance to explore Fabri and the music written for him in Arias for Ballino, a concert presented by Opera Settecento and Leo Duarte at St George’s Hanover Square, in which they were joined by tenor Jorge Navarro Colorado.

Some 80 minutes of rare Baroque arias might sound somewhat forbidding (three of the arias, including those from Handel’s Scipione, were first performances in modern times) but with performances so wonderfully engaged and engaging we were entranced. This seems to be very much a passion project for Jorge Navarro Colorado: he described in the programme how singing his first two complete Handel operas (Lotario in Halle, and Partenope) he discovered that both roles fitted him well and that both were written for Fabri, which impelled him to go in search of other arias written for the tenor. And what music it was. Clearly Fabri was rather keen on insanely long passages of very fast notes, and even the more lyrical arias were quite busy (in the manner of Johann Adolph Hasse). By the end of the evening, we had a clear idea of Fabri’s tenorial style, but this was far more than an academic exercise.

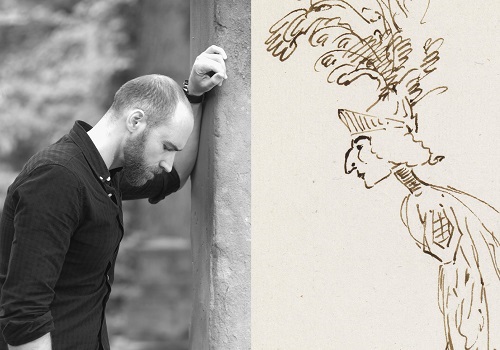

Pen and brown ink drawing of Annibale Pio Fabri (‘Ballino’) c.1720-30 by Anton Maria Zanetti the Elder (courtesy of The Royal Collection Trust)

Singing from memory (that is twelve arias in total) Navarro Colorado succeeded in making this music count dramatically. No matter the technical complexities, he never lost sight of the drama and for each aria conjured a sense of character and pace. Words were terrific, spat out where necessary and always present. Born in Spain and trained in the UK, Navarro Colorado is clearly not just happy in Italian but can use the language expressively in this complex music. Tall and distinguished-looking, he cut a striking figure and was adept at using his face to complement the expressivity of his singing. His voice has a fine, strong middle which seems very necessary in this music (Fabri’s range was from B to a’) where a lot of the busier passages sat, but Navarro Colorado also has a lovely free top. We were able to be dazzled by his singing, be amazed by the crazy music but never did we have to worry about whether he would make it. All was free and easy

These were vivid performances, wonderfully supported by Leo Duarte and the orchestra of Opera Settecento. Duarte directed from the oboe; his body language often wonderfully expressive in its own right.

Fabri only sang for two seasons for Handel, but he received several new roles including Berengario in Lotario, Emilio in Partenope and Alessandro in Poro. Handel also re-wrote Scipione for him and got him to sing other tenor roles, including the tenor version of Sesto in Giulio Cesare and Tiridate in Radamisto. We began the evening with Scipione: the Sinfonia from Act II, plus two arias from the 1730 revision of Scipione (which had premiered in 1726) when Handel re-wrote the title role (which had originally been for alto castrato) for Fabri. The two arias had never been performed in modern times so clearly this version of Scipione needs a proper looking at in the theatre. The first aria was a cavatina, strong and slow with just continuo, whilst the second (the first of many da capo arias in the evening) featured fast vivid passagework which was seemingly never-ending, and in the da capo Navarro Colorado went even further and filled in some of the gaps. But it was never a mere sport, this was vividly dramatic stuff.

Next came a pair of arias from Trajano by Neapolitan composer Francesco Mancini (1672-1773), which premiered in Naples in 1722. Both felt somewhat old-fashioned, certainly not the more modern style of composers like Vinci, but full of contrapuntal interest in the orchestra complementing a tenor part which moved from the lyrical to the busily fast.

Fabri had a long relationship with Antonio Vivaldi, performing some of the composer’s operas in Venice early in his career. So, it made sense for Leo Duarte to include Vivaldi’s Oboe Concerto in D minor. It is in three movements – fast, slow, fast – the outer movements featuring lots of engaging rhythmic interest in solo and accompaniment, full of energy and very toe-tapping, with a calmer slow movement featuring a still elaborate solo part. Throughout, Duarte played engagingly and seemingly with an endless supply of breath.

We heard two arias from Vivaldi’s L’Incoronazione di Dario (which premiered in Venice in 1716), both quite lively with busy orchestral textures and in the second a fast-moving bass line which often doubled the voice to striking effect. This latter was a furious aria, ‘With the fury in my breast, I will pierce the proud hearts of my rivals’, and Navarro Colorado really spat the words out in vivid fashion. In between, we heard from Francesco Corselli (1705-1778), an Italian born of French parents who ended up working in Madrid! His Farnace premiered in Madrid in 1739 and judging by the aria we heard, the work is worth investigating, with interestingly complex writing for the orchestra complementing the voice nicely.

Francesco Scarlatti (1666-c.1741) is certainly not a well-known name. The younger brother of the better-known Alessandro (and thus uncle to Domenico), Francesco came to London around 1719. Not that much music survives, but in 2002 a group of twelve sonatas by him were found written in one of the work-books of Newcastle composer Charles Avison (1709-1770). We heard one of these, more akin to a concerto grosso than a sonata and full of the sort of contrapuntal interest that might have been a touch old-fashioned but was clearly beloved of the English (Avison, the transcriber, had studied with Geminiani in London). The final slow movement has strong echoes of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons (notably Spring).

The operas of Antonio Caldara (1670-1736), an Italian working in Vienna, are still not as well-known as they deserve to be. This is partly due to Caldara working for the Imperial family, after his operas premiered the music tended to disappear into the Imperial Archives (where the scores remain) rather than being widely disseminated to his contemporaries. Adriano in Siria premiered in 1732 in Vienna and we heard two arias from it: both simile arias, the first vivid and strong, the second vigorous with a nice spring to the rhythm, and both full of imaginative orchestration complementing the crazy writing for the tenor. In between, we heard from Francesco Scarlatti’s elder brother Alessandro Scarlatti (1660-1725); his Marco Attilio Regolo which premiered in 1719. Here the protagonist was lovelorn but still managed to fit in some busy passages alongside the lyricism.

We finished with a pair of arias from Handel’s Partenope which premiered during Fabri’s first season in London. His role, Emilio, is not one of the major protagonists and quite late in the creation of the opera, Handel decided to transfer the aria ‘Qual farfaletto giro a quel lume’ from his character to the title role, and this is how we know it, but we heard it in the version Handel must have first conjured, with Fabri’s voice in his ear. There was a nice lilt to the rhythm, with Navarro Colorado bringing a lovely ease to the busy passages and projecting an engaging personality. Then we ended with what Leo Duarte introduced as Jorge Navarro Colorado’s favourite aria, Emilio’s ‘Barbaro fato’ from Partenope, another one full of insane passagework complemented by dramatic orchestration, and all performed with wonderful character and personality.

There was an encore. Whilst in London, Fabri also sang in two pasticcios and Venceslao includes an anonymous aria which just might be by the singer himself (who was a composer). Certainly, its style fitted with the arias we had already heard, and it ended this wonderfully engaging concert in a vividly crazy fashion.

Opera Settecento is currently fundraising to try and turn this programme into the group’s first commercial disc. There are a range of support schemes available from their website.

Robert Hugill

Arias for Annibale ‘Ballino’ Pio Fabri: Jorge Navarro Colorado (tenor), Leo Duarte (oboe, director) Opera Settecento

St George’s Hanover Square, London; Friday 15th October 2021.

ABOVE: Leo Duarte (centre) and Opera Settecento