Very little exists in a visual way of Wieland Wagner’s Bayreuth Die Walküre from the mid-to-late 1960s. What does, largely requires us to use our imagination. It is something which we were also asked to do with Richard Jones’s new production of Valkyrie for English National Opera. This, I have to say, proved very challenging.

The comparisons with the two Walküren, and with Wagner and Jones, is perhaps much less loose than one might imagine. Wieland Wagner’s opera can only be seen semi-staged – and yet there is a very semi-staged feel to Jones’s production. Perhaps we should cut him some slack; after all, Brünnhilde’s ring of fire was scrapped under the instructions of Westminster Council as a fire hazard (although I have seen the Royal Opera House go up in flames many times).

The most narrative driven of the four operas in the cycle, Valkyrie shouldn’t prove too much of a challenge in getting the actual story across – and largely that wasn’t an issue here. John Deathridge’s new translation is less humane, less willing to charm than Andrew Porter’s old one did – it is, if you like, more Teutonic. It is also less lyrical, which often put it at odds with singing Wagner in English and more in favour of the Romanticism of Wagner’s score. This caused some problems, which may not have been an issue in German. The long exchanges between Siegmund and Sieglinde in Act I felt exhausting – often because they struggled with the one thing they were supposed to have, raw intensity. There is nothing wrong with Deathridge’s translation – in fact, it is magnificent from what I have read of it – but its ambitions are more Homeric than they are operatic.

If this does share one thing with Wieland Wagner’s staging it is scale. The depth of the ENO stage is impressively used to convey the inescapable forest and it needs nothing more simple than massive curtains and some light shifting to make it work. Designer Stewart Laing has given us something epic to play with but that’s really the problem – no one does play with it. There is nothing. A vast emptiness as bewildering and desert-like as the Prairies. The Ring will always be here, a circle in the dust, rain or snow. But it neither glistens nor is it gold. It’s tarnished, semi-buried and, of course, never gets a chance to be surrounded by flames.

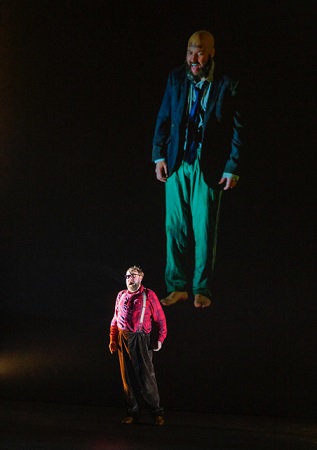

When we first meet Sieglinde and Siegmund it is in a wood cabin built around a tree where the sword of Nothung is impaled. The shelves are stacked with wood grease, oil cans and chopped logs. Their illicit love will be carried on with the abusive Hunding sleeping above. Insofar as the costumes suggest we are to be relatable to Siegmund and Sieglinde, as opposed to Hunding, it works: the lumberjack shirt and trainers versus the chain-gang, road-filth work jacket and threatening boots covered in black grease. His booted, T-shirted kinsmen are no better. It’s the spear versus the wood-axe. But costume is important elsewhere: Brünnhilde with her breastplate, but girlish enough to be in shorts (designer, if you perhaps notice her own logo down the sides) and sneakers, linking her dual status as mortal and immortal. Wotan, not with an eyepatch but with spectacles of black and clear lenses – so it is easier to see what Wotan sees and what he doesn’t. The Valkyries are in very oversized green cagoules looking as if they have been swept ashore from a Herman Melville novel. Where are we and what it all means – well, any one’s guess.

Moments that might have been striking weren’t when you thought you had seen them elsewhere. Act III opens after the massacre that is the end of Act II – the slayings of Siegmund and Hunding – with the Valkyries on their horses lifting up the bodies of the dead on their spears. It is more than a little reminiscent to the brutal opening to Coppola’s Dracula – so much so you wish that ENO had done something spectacular with the colour for such a seminal scene in the opera. But colour was a significant issue through much of this production – or the real lack of it. Valkyrie need not look like a washout, as if it really were set in Kansas.

With so much of Jones’s Valkyrie reliant on a what-you-see basis, there was little scope for something out of the ordinary to insert any remaining interest. Jones is not a director who cares much for gimmicks so video was sparse – only rarely did you get use of Akhila Khrishnan’s installations. The reminder that Alberich is always present was unmistakable – ‘Nibelung’ tattooed across his forehead. There was a creepy yet terrifying puppetry to the horses – a semi-irony that they couldn’t be ridden but were, too, being controlled as almost everything and everyone is in this power struggle between gods and mortals.

The casting was generally strong. Nicky Spence and Emma Bell were both making role debuts as Siegmund and Sieglinde. Both singers have to carry Act I and they did so very well. Sieglinde is difficult to cast and Bell does not fit into the more lyrical of sopranos for the role – the voice, if with a good range, can sometimes sound less than youthful. However, she hits the notes and she is a good foil in her exchanges with Brünnhilde in Act II. Nicky’s Spence’s Siegmund, on the other hand, is thrilling. A tenor who rang out “Walse!” with the range and scorching power that Spence did showed no sign whatsoever of the lingering cold which had threatened his performance altogether. Spence and Bell made much of their passionate climax – but then this is some of the most erotic music ever written. They may have literally been running in circles doing it, but it hardly mattered when the music sounded this thrilling.

Matthew Rose’s Wotan – although thoughtfully, if sometimes neurotically acted – will I, think, divide opinion. The voice is huge, and made even more so by how this production is staged. Jones has placed all of the action to the fore of the stage so voices seem much closer than they would normally do. But it’s not a subtle performance of Wotan either; at least not until we get to Wotan’s rage and his final scene with Brünnhilde when a more moving portrayal of the character emerges. Brindley Sherratt’s Hunding, on the other hand, is magisterial – powerful and malevolent it has all of this singer’s trademark brilliance in Wagner.

Rachel Nicholls sang a Brünnhilde full of nuanced touches but she often found herself in the shadows of others. She was no match for Spence’s Siegmund in Scene 4 of Act II, nor for Bell’s Sieglinde in Scene 1 of Act III. Nicholls was often less favoured by the staging and often had to sing from centre stage and it pointedly illustrated the weaker limits of her voice. Susan Bickley, because of illness, could only act the role of Fricka which was instead sung (superbly) by Claire Barnett-Jones, who also sang Roßweiße.

Martyn Brabbins takes a very leisurely view of Wagner’s score – not quite as leisurely as Goodall did, but it often felt it. A fleeter approach would have helped – it was clear that some singers like Rose and Nicholls may well have benefited from gutsier conducting. But there were surprising moments – the ‘Ride of the Valkyries’ didn’t fall into the trap of being an orchestral showpiece, and nor was it on the slow side which can so easily happen. On the other hand, there were moments during the Sieglinde-Siegmund love duet where the music came close to stasis. But almost all of this can be forgiven when the playing from the orchestra sounded as ravishing as it did here. Opulent strings, rich brass. It was a triumph.

But perhaps not enough of one to save what is at times a rather uninspiring production. I think I know where Richard Jones’s Valkryrie aims to go; it’s just there is a level of under-ambition when you see it. Ironically, the one scene that might be termed ‘over-ambitious’ is the one that was scrapped – at least from the production still – as all we see is Brünnhilde being winched up to the heavens. We were being asked to imagine what we couldn’t see. And, unfortunately, that turned out to be the problem. After five very long hours, my imagination had long deserted me.

Marc Bridle

Siegmund – Nicky Spence, Sieglinde – Emma Bell, Hunding – Brindley Sherratt, Wotan – Matthew Rose, Brünnhilde – Rachel Nicholls, Fricka – Susan Bickley (sung by Claire Barnett-Jones), Gerhilde – Nadine Benjamin, Ortlinde – Mari Wyn Williams, Waltraute – Kamilla Dunstan, Schwertleite – Fleur Barron, Helmwige – Jennifer Davis, Siegrune – Idunnu Münch, Roßweiße – Claire Barnett-Jones, Grimgerde – Katie Stevenson; Director – Richard Jones, Conductor – Martyn Brabbins, Designer – Stewart Laing, Lighting Designer – Adam Silverman, Movement Director – Sarah Fahie, Video Designer – Akhila Krishnan, Orchestra of English National Opera.

The Coliseum, London; Friday 19th November 2021.

ABOVE: ENO, The Valkyrie, Rachel Nicholls (Brünnhilde), Matthew Rose (Wotan) © Tristram Kenton