Theodora is ‘coming home’ … but not as you know it, was the essential message of the press briefings issued by the Royal Opera House in the run up to the first staging of Handel’s oratorio at Covent Garden since its premiere in 1750.

272 years ago, Handel’s fears that his ‘favourite’ oratorio would not be well-received – ‘the Jews will not come because it is a Christian story, and the ladies will not come because it is a virtuous one’ – proved correct, for these and other reasons, including an earthquake in London that kept timid theatregoers at home. Theodora languished unperformed and unremembered until the 1990s when Peter Sellars’ Glyndebourne production, and in particular the performance of the late Lorraine Hunt Lieberson in the role of Irene, brought it out of the shadows. For its Covent Garden homecoming, Theodora was, we were told, to undergo a radical reinterpretation by director Katie Mitchell. Librettist Thomas Morell’s account of female virtue, heroism and faith would receive a feminist make-over, the eponymous heroine being transformed from a passive Christian martyr to a Christian fundamentalist with ‘agency’. There would be ‘explicit presentation of scenes of sexual violence, harassment and exploitation’ – an ‘intimacy coordinator’ (Ita O’Brian) had been appointed to support the cast during rehearsals – and under-sixteens should be kept well away.

In the event, the pre-curtain clamour proved rather hyperbolic. Mitchell updates the setting, turning the governor’s palace in 4th-century Antioch into a Roman embassy in a modern-day city-state. The Christians are not merely trying to covertly practise their faith, but, while slaving in the embassy kitchen, are actively plotting anti-state terrorism. Morell’s straightforward scenario is largely maintained, though. Theodora refuses to submit to Valens’ tyrannical edict that all the citizens should pay homage to Venus and is condemned to work in the ambassadorial brothel – the cruellest punishment possible for a woman whose integrity it founded on her chastity. The Christians, now led by Theodora’s closest friend Irene, continue to cook-up incendiary devices in the kitchen, while Didymus, a Roman convert who loves Theodora, determines to rescue his beloved by swapping places with her. When he is subsequently condemned to death for his treason, Theodora comes out of hiding to fulfil her Christian destiny, offering herself in his place. In the event, Valens commands that they both be executed.

At which point, Mitchell effects a huge swerve and totally re-writes the ending, her reasoning being that, far from being submissive or passive, Theodora has ‘resigned herself to the use of violence to achieve her religious ends’. I’m not so sure about the Antioch princess’s ‘passivity’: after all, she makes many choices, driven by her religious fervour, in the course of the oratorio, first spurning the society which, as a princess, she should lead; then refusing to heed Irene’s appeals in pursuit of her unfaltering ideals; and finally sacrificing her life, not out of love for Didymus but in the spirit of martyrdom, thereby ensuring her eternal bliss in heaven.

Moreover, Mitchell’s updating rather dilutes the spirituality of the oratorio which pits Christian devotion against Roman decadence. Her Christians want to ‘actively destroy the Roman order’, but it’s not really clear why. We see them working in the kitchen and serving in the embassy’s grand reception room, but for all the incessant floor-mopping, glass-wiping and general skivvying they don’t really seem very ‘oppressed’, and certainly not on account of their religious convictions. A white tablecloth transforms the kitchen island into an altar, Didymus is baptised by serving bowl, and the knife-rack forms a surreptitious cross, but the symbols make a weak impact. The Christians are less interested in singing carols round the Christmas tree than in pursuing alchemical experiments in the art of detonation. One wonders, too, if Didymus, who spends his first two numbers arguing against religious persecution and for freedom of belief, would really be so keen to join a bunch of murderous fundamentalists for whom its hard to feel much empathy.

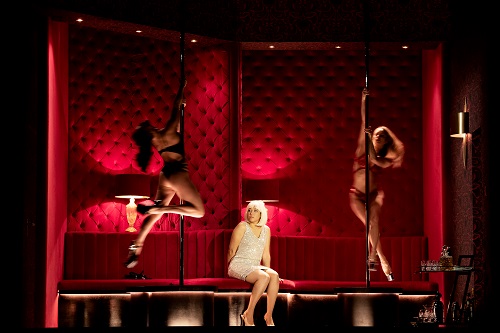

Chloe Lamford’s set design is effective, its four low boxes sliding back and forth, the central kitchen and state room framed by the brothel, all voluptuous red velvet, and a cool-blue walk-in refrigerator. The outer rooms neatly epitomise Mitchell’s wish to emphasise the hypocrisy and misogyny of the male Roman rulers, the meat carcasses hanging from the cruel hooks in the deep freeze being juxtaposed with the two barely clad pole-dancers whose sinewy girations entertain the brothels’ guests. The two dancers’ impressive acrobatics (movement director, Sarita Piotrowski) are, however, something of a distraction during Theodora’s ‘With Darkness Deep’, and such visual diversions mar the whole production, as the arias – most of which Handel marks Largo or Larghetto – are not given space to communicate directly to the audience, the music being clouded by constant and disruptive movement and image. And, given that Mitchell is supposedly aiming for a nuanced representation of female oppression, I was somewhat surprised to find soprano Julia Bullock, who is singing the titular role, being quoted in the programme as stating that ‘there’s a difference between the sex workers who are seemingly empowered in some way – they are there for their job, they are paid well for their work – versus the situation with Theodora’. I’m not sure that ‘sex workers’ and ‘empowered’ are words that I would consider likely bed-fellows.

These missives aside, Mitchell does construct a compelling drama, which draws us into the characters’ psychologies and decisions, though there are some stumbling blocks and non sequiturs. The movement and thus the characterisation of the ROH Chorus, who were in fine voice but took a little time to catch up with conductor Harry Bicket in the opening Act, are inhibited by the huge central island in the kitchen and the long table in the reception room. And, in any case, the fugal choruses don’t lend themselves to dramatic ‘enactment’ – the ‘drama’ is in the musical form itself.

Moreover, the coherence of text, music and action at any one moment is rather hit-and-miss. To take one example, Mitchell explains that she was determined to have Theodora on stage from the start, even though she doesn’t sing for 30 minutes, so that we see the world through Theodora’s eyes; but, it makes no sense for Ed Lyon’s Septimius to direct his response to Didymus’s request that clemency be shown to the Christians – we can only pity those whom we cannot spare, he explains, imploring in his Air, ‘Descend, kind Pity, heav’nly Guest’ – at Theodora herself. Then, in Act 2, following the aforementioned ‘In Darkness Deep’, Theodora asks herself, “But why art Thou disquieted, my Soul?”, and is consoled in ‘O that I on Wings cou’d rise’ by thoughts of the eternal joy to come in the hereafter. But, her faith that “I might rest, For ever blest, With Harmony and Love” is directed not heavenwards but at the ‘meanest’ of Valens’ guards who has been sent to the brothel to ‘triumph o’er her boasted Chastity’ with ‘lustful joy’ – as she fiercely points at him the pistol that she’s wrenched from his grasp. Indeed, there’s an awful lot of such pistol-pointing, and it becomes rather tiresome. I wasn’t entirely convinced by the slow-motion charades the accompanied some of the arias, either.

Despite these irritations, there’s some terrific singing to enjoy, though it’s not always very Handelian in flavour. The least idiomatic performance comes from bass Gyula Orendt whose Valens is a ghastly, lust-fuelled hedonist and who shows little appreciation for Handel’s vocal phrasing or line. Ed Lyon’s Septimius is more stylish and his tone firm and ear-pleasing. He negotiates the floridity of his arias with relaxed ease too. But, the way Septimius is torn between duty and friendship – being both Valens’ right-hand man and Didymus’s closest friend – and between loyalty to the state and growing sympathy for the Christians (in Morell’s conclusion, which Handel did not set, he and other Romans convert to Christianity) – is sadly weakened because in this production Septimius becomes increasingly unfeeling.

In all of Irene’s arias, Joyce DiDonato brings both humanity and musical sincerity to the foreground, through her varied tone colour, sensitive ornamentation and because her musical authority is such that we are drawn, no compelled, to listen to the music. ‘Lord, to thee each day and night’ made time – and everything else – stand still. Julia Bullock conveys Theodora’s resoluteness but isn’t really at home with the style and, though she sings with lovely warmth at the top, projects unevenly lower down. Jakub Józef Orliński truly gives his all as Didymus, and it’s probably his total commitment that stops the costume-swapping in Part 2 – when he dons the silver-sequinned mini-dress and peroxide wig that Theodora has been forced to wear, to enable her to escape disguised as him – from becoming pantomimesque. Orliński’s ringing countertenor is wonderfully rich and full, and he does have a natural affinity for the style. His two duets with Bullock were highlights, their voices blending with particular sweetness in ‘Streams of pleasure’, in which the now-married Didymus and Theodora prepare for their death with calm assurance.

What a pity that Mitchell doesn’t listen to their music. For, it embodies the ‘happy ending’ that Handel’s first audience felt was lacking from Theodora, which seemed to them to close with the unjust deaths of these exemplary, righteous Christians. But, their song expresses their serene confidence in the blessings that they will receive in heaven, just as throughout the opera Handel’s radiant, tender arias evoke the state of spiritual happiness to which the characters aspire. Mitchell’s so-called ‘red interventionism’ denies the music the opportunity to work its magic.

Claire Seymour

Theodora – Julia Bullock, Irene – Joyce DiDonato, Didymus – Jakub Józef Orlinski, Septimius – Ed Lyon, Valens – Gyula Orendt, Marcus – Thando Mjandana, Actors and Dancers – Aquira Bailey, Browne, Ben Clifford, Sarah Northgraves, David Rawlins, Holly Weston, Kelly Vee; Director – Katie Mitchell, Conductor – Harry Bicket, Set designer – Chloe Lamford, Costume designer – Sussie Juhlin-Wallén, Lighting designer – James Farncombe, Movement director – Sarita Piotrowski, Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal Opera House (William Spaulding, chorus master).

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Monday 31st January 2022.

ABOVE: (Theodora) Julia Bullock © Camilla Greenwell