In a 1949 broadcast, Sir Arnold Bax (1883-1953) declared: ‘Yeats’ poetry means more to me than all the music of the centuries.’ And, when the Irish poet and dramatist died in 1939 Bax lamented that ‘the greatest of us all is no more’. In 1902, through reading the poetry of W.B. Yeats, had Bax discovered the Celtic culture – music, literature, language, people – that would capture his heart and mind, and find expression in his music, and literary writing, throughout his life. The west coast was particularly beloved, wild and ‘primeval’ as it seemed.

This is the Bax with whom most enthusiasts of English music of the first half of the twentieth century will be familiar: the composer of orchestral works suffused with Celtic inspiration – In the Faery Hills, Tintagel, The Garden of Fand –and who, under the pseudonym, Dermot O’Byrne, published Irish folk-inspired poems and songs. It was surely fitting that Bax, knighted in 1937 and appointed Master of the King’s Musick in 1941, should have died in Ireland, 36 days prior to his seventieth birthday, in Cork in 1953.

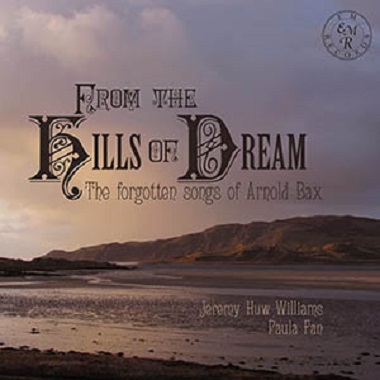

But, if it is for his Celtic-tinted orchestral ‘mood-pictures’ and his seven symphonies – as well as a few other large-scale works, such as Winter Legends for piano and orchestra, and chamber works such as the Piano Quintet and Viola Sonata – that Bax is best known today, then he was also the composer of over 130 songs and vocal arrangements. Some date back to the years just before Bax began his studies at the Royal Academy of Music, and all but one were composed between 1900-30. On this English Music Records release, From the Hills of Dream, baritone Jeremy Huw Williams and pianist Paula Fan present eighteen of Bax’s songs, none of which have previously been recorded and five of which are performed for the first time here.

It’s perhaps not surprising that Bax, who was such a gifted lyrical tone-poet, was attracted to the medium of song. His earliest efforts in the genre met with mixed a critical reception, though, their melodic fluency praised but their complex accompaniments found less successful. The Times critic, commenting on a programme of Bax’s music which was performed at the Aeolian Hall on 16th July 1908, admired the ‘great inventive power’ revealed by Bax’s string quintet, but found this invention ‘a serious hindrance to the success of his songs’ which were judged to be ‘over-elaborated, especially in the piano accompaniments’.

Williams and Fan present their chosen songs in chronological order, offering the listener an opportunity to observe Bax’s developing style. The earliest song, ‘The Grand Match’, was written in 1903, the year in which the nineteen-year-old composer first travelled to Ireland and discovered the village of Glencollumcille in Donegal to which he would return many times. The song sets a text (by ‘Moira O’Neill’, the pseudonym of Agnes Nesta Shakespeare Skrine) peppered with Irish dialect, which tells of a young lad, Dennis, who lives to rue the day when he put purse before passion and married a rich but harsh-tongued girl, rather than the beautiful grey-eyed Nannie who had caught his heart. Listening to the melodramatic (bombastic?) piano introduction to what is essential a trite ditty, one sympathises somewhat with the aforementioned Times writer. Fan fully enters into the musical spirit, gets her fingers round the fistfuls of notes, and observes every detail of accent, dynamic and colour, but it feels like a lot of hard work for what is essentially – to borrow Dennis’s dismissal of the ‘dark little patch’ that mars his wife’s appearance – “a thrifle”.

Williams’ approach to the song has a fitting ‘robustness’ – after all, Dennis is not exactly a discriminatingly reflective chap – but the very ‘forward’ recorded sound and Williams’ pervasive, wide vibrato (particularly pitch-disturbing when Bax employs ironic melismatic rhyme, “She brought him her good-lookin’ gold to admire,/ She brought him her good-lookin’ cows to his byre”) are rather unsettling. The wobble muddies the enunciation of the text, too. And, one wonders if falsetto is really required for Nannie’s wry quip, when Dennis comes seeking solace: “She said, ‘How is the woman that own’s ye?’”

‘Leaves, Shadows and Dreams’ (1905) may set just two short verses by ‘Fiona Macleod’ (Scottish writer, William Sharp) but, with its syncopated complexity and wealth of pianistic detail, it has sufficient contrapuntal argument to fill a symphonic movement. Similarly, the simple sentiment conveyed by the nature imagery in Macleod’s six-line poem, ‘Longing’, is eked out – literally so, in the form of rather shapeless elongated vocal lines which quiver unstably at times – to four minutes of musical meandering. But, ‘To my Homeland’ (1904) is a much simpler strophic setting; here, Bax’s piano writing is sparse and fresh – just a little dialogue and interplay with the voice. Williams makes a meal of it, though, with exaggerated contrasts of dynamic and colour, with shifts to and from falsetto in the repetitions of the final line, “Keep me in remembrance, Long leagues apart”. Again, the text is often rendered unrecognisable: various vowel sounds – ‘Ireland’, ‘father’, ‘mountain’, ‘yearnings’ – become an indistinguishable ‘ah’. What’s really needed here is directness, unadorned lyricism, and accuracy of pitch, all of which are somewhat lacking here.

‘Viking-Battle Song’ (1905) has a sturdy dramatic stamp – Fan strikes out with a warlike vigour in her step – and Williams certainly has the necessary heft: if only vowels and vibrato had been brought into a more disciplined partnership. But, one also feels that Bax tries too hard to make something of the pretty dreadful text, “Far off the ravens cry Death-shadows cloud the sky. Let the wolves,/ the wolves of the Gael die. ’Neath the screaming swords!” In ‘I fear thy kisses, gentle maiden’ (1906), a setting of Shelley, one senses a more individual harmonic idiom coming to fruition, and there’s more sensitivity and nuance from Williams too. ‘The Twa Corbies’ is one of two recitations with piano accompaniment that Bax wrote in 1906. The traditional Scots ballad dates from the 18th century and was first published in Walter Scott’s Minstrelsy in 1812. Williams makes no attempt at a Scots brogue. Nor does his delivery of the recited text convey the tale’s cynicism – the ravens (‘corbies’) tell of the disloyalty of the master’s hawk, hound and mistress – or pessimism: the birds pluck out the man’s eyes, but such is the stuff of life – “The wind sall blaw for evermair.” There’s a chance to tell a ripping yarn here, but it’s not taken.

Two later Chaucer settings, ‘Welcome, Somer’ and ‘Of her Mercy’ (1914) flow forward with more natural motion; Bax’s melodies seem more obviously responsive to both the rhythms and the sentiments of the text too, and the piano writing is less inclined to overwhelm the voice with highly wrought complexities. Fan and Williams convincingly convey the emotive strength of George Russell’s ‘A Leader’ (1916), written in memory of various Irish patriots; here Bax’s musical structure effectively complements the poem’s progression towards a vision of Ireland as a repository of ancient mystical knowledge. The composer seems have struggled to refine his setting of Tennyson’s ‘Blow, bugle, blow’, working on ‘The Splendour Falls’ between 1912 and 1917. The results are rewarding though: this is a beautiful setting, lyrical, elegiac and touchingly pensive, and it’s performed sensitively by Williams and Fan. Thomas Hardy’s ‘To Carrey Clavel’ is one of the ‘A Set of Country Songs’ in the poet’s collection, Time’s Laughingstocks,and presents the complaint of a simple country lad whose love is scorned by the eponymous lass. Bax’s setting captures something of the poem’s tripping ballad meter but perhaps not the sympathetic sincerity of the spurned speaker’s feelings.

In his 1943 autobiography, Farewell My Youth, Bax remembered his visits to the west of Ireland, where he was ‘always seeking out the most remote corners I could find on the map, lost corners of mountains, shores unvisited by any tourist and by few even of the Irish themselves … for me all these faraway places were alike bathed in supernal light … I worked very hard at the Irish language and steeped myself in history and saga, folk-tale and fairy-lore.’ One senses the almost spiritual transformation that the encounters brought about for Bax, these ‘faraway places’ seeming to hover between two worlds, the real and the fantastic. Indeed, the composer wrote:‘The Celt has ever worn himself out in mistaking dreams for reality, but I believe on the contrary, the Celt knows more clearly than the men of most races the difference between the two, and deliberately chooses to follow the dream.’ Such feelings imbue the eponymous ‘From the Hills of Dream’ (1907), which has a ‘faerie’ spirit rustling through its rippling through its gently rising and tumbling piano motifs and atmospheric harmonies. The vocal phrases – which float upwards delicately, aspiring and hopeful – require a lighter touch, though, if the song’s dreamy ethereality is to be evoked. Williams again resorts to a quite heavy falsetto that sometimes strays from the intended pitch – rather unfortunately so, given that the phrases often end with a high, sustained note. It’s a pity as this is a lovely, characterful song, its proportions apt and well-crafted, and this recording is thought to be the first time it has been performed.

The disc also presents some of Bax’s settings of foreign texts (translations are provided in the detailed liner booklet). ‘Landskab’ (1908, Landscape) interprets a poem by the Danish writer Jens Peter Jacobsen, and reflects Bax’s long-standing interest in the Nordic world. There’s a welcome ‘stillness’ about this song: the piano’s thoughtful pulsing harmonies are evocative, and Fan paints varied colours and textures, while the lower-lying vocal line finds Williams more focused, though there is still a tendency to surge and ebb exaggeratedly, rather than craft lines of tender evenness such as seem to be needed here. ‘Das tote Kind’ (1911, The dead child) is much more successful, Conrad Ferdinand Meyer’s eerie imagery inspiring a dramatic, persuasive response from Bax. The German text is crisply enunciated by Williams, and here the changes of tone colour and volume are entirely apt, as the baritone declaims with fierce, warm force the garden’s cries to the dead child to come forth from her hiding place. Two French settings, ‘Le Chant d’Isabeau’ and ‘A Rabelaisian Catechism’, both dating from 1920, are less appealing, largely because their content is not sufficiently rich to sustain their seven-minute length.

Bax’s music may not have historical significance in terms of the development of modern English music. As he himself admitted, in July 1920: ‘I am a brazen romantic, and could never have been and never shall be anything else. By this I mean that my music is the expression of emotional states. I have no interest whatever for sound for its own sake or in any modernist ‘isms’ or factions.’[1] Nor are his songs the finest of him. But, Bax aficionados will welcome this disc for the ‘firsts’ that it offers. Almost all the songs on this disc were transcribed from Bax’s manuscripts by Dr Graham Parlett, a former curator of Asian Art at the Victoria and Albert Museum who dedicated many decades to researching the life and music of Bax, and whose 1999 Catalogue of Bax’s music for Oxford University Press remains the definitive volume on Bax’s music, containing as it does an exhaustive survey of the composer’s musical and literary output. Dr Parlett’s liner article and his detailed notes on each of the songs here are exemplary, engaging and informative. From the Hills of Dream is dedicated to his memory.

Claire Seymour

From the Hills of Dream: Jeremy Huw Williams (baritone), Paula Fan (pianoforte)

Arnold Bax: ‘The Grand Match’, ‘To my Homeland’, ‘Leaves, Shadows and Dreams’, ‘Viking-Battle-Song’, ‘I fear thy kisses, gentle maiden’, ‘The Twa Corbies’, ‘Longing’, ‘From the Hills of Dreams’, ‘Landskab’, ‘Marguerite’, ‘Das tote Kind’, ‘Welcome, Somer’, ‘Of her Mercy’, ‘A Leader’, ‘The Splendour falls’, ‘Le Chant d’Isabeau ‘, ‘A Rabelaisian Catechism’,’ Carrey Clavel’

EMR CD073 [77:56]

[1] R.H. Wollstein, ‘Bax defines his music’, Musical America, 48 (July 1928), p.9.