To describe Saint-Saëns’s Samson et Dalila as ‘old-fashioned’ doesn’t seem controversial. The French composer’s score harks back to the past with its allusions to Handelian fugue and Bachian chorale, betraying its oratorio-origins, and the story drawn from the biblical book of Judges has sacrificial heroism, passion across enemy lines, betrayal and brutality, and cathartic vengeance – all the ingredients of operatic drama and spectacle.

But, Richard Jones was never going to present a fervent biblical ‘epic’ nor headily perfumed orientalism in his new production of Samson et Dalila at the Royal Opera House. So, it’s no surprise that there is little religious fervour – this Samson is more street-fighter than spiritual leader – on the Covent Garden stage, and the only gold lamé in evidence is on the scalp of the Philistine governor, Abimélech. Instead, Jones pares back the opposing ideologies, largely stripping the conflict between Hebrew and Philistine of any theological flame – though there are a few ritual scenes where feet get washed and suchlike – and presents the drama as a choice between moral asceticism and iniquitous materialism.

Designer Hyemi Shin provides appropriately minimalist designs. The Temple is a white box, its starkly lit interior filled with sharply raked steps, which is dragged on and off as required. Dalila’s house has a similar flat-pack simplicity, a single-story oblong furnished only with a ceiling-fan that loops lazily and a long table which proves useful for laying out the bloodied dead. The uncluttered stage is aptly roomy for the choreographed choral spectacles, though it’s hard for the eponymous protagonists to convincingly ‘connect’ and convey overmastering passion across the empty expanse. Lighting designer Andreas Fuchs frequently swathes the back wall with vibrant orange, complementing the clashing orange-blue of the Philistines’ shiny casuals, while costume designer Nicky Gillibrand dresses the Hebrews in shades of ghetto-grey. There’s little sense of time or place, but while Jones has eschewed allusion to any modern-day conflict, the High Priest of Dagon’s fur-trimmed bomber jacket and bullying swagger evoke the brutal oppression of post-war totalitarianism or a tin-pot dictatorship.

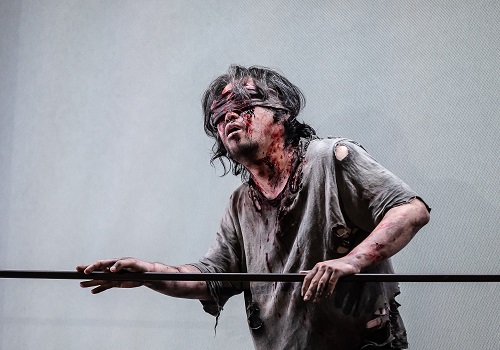

Samson et Dalila is rather static in that its long scenes are juxtaposed rather than evolve organically – even the crux of the drama, the haircut and the subsequent blinding of Samson, takes place off-stage – and Jones essentially presents the scenes as a series of tableaux vivants in which certain visual images do the dramatic heavy work. So, the blood-drenched white torso of the assassinated Abimélech is carried back and forth, becoming the apparent motivation for Dalila’s duplicity, intimating that she’s more than merely a stereotypical seductress. And, the coiling motions of the ceiling fan are mirrored by the curling of Dalila’s fingers through Samson’s glossy locks in the climactic duet which precedes his undoing. The Bacchanalian orgy, however, is a bit of a damp squib. No semi-naked gyrations or wild, drunken revelry here, rather some Jonesian irony which pitches geeky ’80s line-dancing against the improvisatory freedom of Saint-Saëns’s sensuous score.

On opening night, the extended ROH Chorus sang with stirring sonority and vigour, whether lamenting their subjugation in the solemn opening chorus, ‘Dieu d’Israël’, or gravely reflecting on the destruction of their cities in the fugal ‘Nous avons vu nos cités renversées’. There was real vocal majesty in the Hebrews’ expression of gratitude in the chant-tinged grand prayer, ‘Hymne de joie, hymne de délivrance’, and in the Philistines’ triumphant hymn to their god, ‘Gloire à Dagon vainqueur!’, the complexity of which the Chorus seemed to relish.

Nicky Spence had originally been cast as Samson, but injury forced him to withdraw, and the South Korean tenor SeokJong Baek made his House and role debut. And, he did so with aplomb. Samson’s phrases are extended, unfolding in broad steps, and Baek crafted smooth, firm melodic contours which communicated Samson’s unwavering nobility, while attending, too, to the shades and nuances. Baek cuts quite a slight figure, and perhaps one imagines a Samson with a bit more brawn, but the tenor certainly had presence – ‘Arrêtez, ô mes frères’ was a rousing exhortation to resist and revolt – and he powerfully conveyed Samson’s self-doubts and, in Act 3, his self-castigation for his sin against God and his people, as he was tormented further by bitter reproaches of the off-stage Chorus. Baek had the necessary stamina too: his top notes never faltered, and that final top C rang out strong and true.

Samson’s strength may be his hair, but the opera’s potency depends on its Dalila and the ROH was fortunate to have the Latvian mezzo-soprano Elīna Garanča in a role that she has made her own in recent years. Vocally she embraced a huge range of feelings: passion, hatred, religious fervour, grief, even tenderness, with Jones seeming to intimate that Dalila feels a genuine pang of remorse when she sees Samson’s damaged body. Her high notes were glorious – clear, sensuous and glowing: ‘Ma coeur s’ouvre à ta voix’ was magnificent, a seductive siren song sans pareil. And, she had sufficient strength in her chest register to make both ‘Amour, viens aider ma faiblesse’ and ‘Printemps qui commence’ – the latter was beautifully lyrical – really tell. But, if the mercury generally remained low in the erotic thermometer, then Garanča also occasionally seemed hesitant dramatically, especially in the seduction dance which was little more than a shuffle and a shimmy.

The secondary roles were performed with uniform accomplishment. Polish baritone Łukasz Goliński sang with commanding vigour as the Philistine High Priest and Georgian bass Goderdzi Janelidze was fittingly thunderous as Samson’s Rabbi. Blaise Malaba used Abimélech’s somewhat declamatory phrases to suggest the crassness and ignorance of the governor’s blustering in ‘Ce Dieu que votre voix implore’. In the pit, Sir Antonio Pappano drove forwards with a bracing musical sweep, emphasising the refinement of Saint-Saëns’s compositional eclecticism and expertly balancing the texture.

Jones professes to have eschewed ‘traditional Orientalism’ in his interpretation of Saint-Saëns’s opera. Such a reading would see Samson and the Israelites as embodying ‘the West’, placed in opposition to the alien Philistines, the exotic ‘Other’ the danger of which is embodied in its stereotypes – a cruel tyrant and a sensuous temptress. But, the imagery of Jones’s final Act, which lampoons and lances crass materialism, does in fact conform with orientalist ideology in that the Other becomes, in the words of musicologist Ralph Locke, ‘a blank screen for projecting Western concerns about itself’.

Arriving the land of Canaan, the Philistines forget their own gods and worship new idols. Jones conveys the shimmering superficiality of their devotion by presenting Dagon as a tacky plastic god of gambling, whose icons are a slot machine and poker chips. If the West is to exorcise its own demons, then the Other must be destroyed, and Samson’s suicide-bomber sabotaging of the Temple provides for a suitably cataclysmic catharsis. But, Jones’s conclusion seems somewhat tentative: the wooden rafters wobble but this isn’t a coup de théâtre which brings the house of Hermes tumbling down.

Claire Seymour

Camille Saint-Saëns: Samson et Dalila

Samson – SeokJong Baek, Dalila – Elīna Garanča, High Priest – Łukasz Goliński, First Philistine – Alan Pingarrón, Second Philistine – Chuma Sijeqa, Messenger – Thando Mjandana, Abimélech – Blaise Malaba, Samson’s Rabbi – Goderdzi Janelidze; Director – Richard Jones, Conductor – Sir Antonio Pappano, Set Designer – Hyemi Shin, Costume Designer – Nicky Gillibrand, Lighting Designer – Andreas Fuchs, Movement Director – Lucy Burge, Chorus and Opera of the Royal Opera House.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Thursday 26th May 2022.