Melodrama: literally, the joining of music (melos) and drama. The word has various connotations, though, relating to genre, method and expression. Denoting a work for narrator and instruments, and sometimes titled ‘monodrama’ or ‘declaimed ballad’, melodrama is also a declamatory art, referring to the technique of combining music and speech, a method that can be employed in various expressive contexts – as in the dungeon scene in Beethoven’s Fidelio, or the melodrame delivered by Public Opinion in the introduction to Offenbach’s Orpheus in the Underworld. The most common use of the word today, however, is in association with a heightened form of expression characterised by sentimentality and excess, an intensification of emotions which is frequently accompanied by music which does not simply enhance or amplify but ‘speaks’ what the words themselves cannot literally say.

In the nineteenth century, the Romantic melodrama for reciter and piano was a well-established genre, often performed in intimate settings, to which many composers contributed – Schubert, Schumann, Liszt, Berlioz, even Wagner who, in Melodram Gretchens, used a scene from Goethe’s Faust in which Gretchen is praying to the Madonna with whose suffering she identifies. Such works looked ahead to Schoenberg’s development of sprechgesang in Pierrot Lunaire, and to twentieth-century compositions such as Stravinsky’s L’histoire du Soldat, Copland’s A Lincoln Portrait, Walton’s Façade, Poulenc’s L’histoire de Babar and Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf; and, beyond that, to the use of music in film to heighten the emotional content.

At a time when he was busy composing many of his most renowned lieder and tone poems such as Don Quixote, Ein Heldenleben and Also sprach Zarathustra, Richard Strauss composed two melodramas for voice and piano: Enoch Arden (1897) which presents Adolf Strodtmann’s translation of Tennyson’s poem, and Das Schloss am Meere (The castle by the sea, 1899) which is based on a short, atmospheric poem by Ludwig Uhland. Strauss’s decision to turn his attention to the genre was driven as much by pragmatic as by artistic design. In 1896, the actor Ernst von Possart had helped the composer obtain the position of chief conductor at the Munich Opera and as a way of returning the favour Strauss wrote the two melodramas as vehicles for Possart, who was much admired as reciter of poetry. The composer-actor duo toured the works extensively, their performances reportedly very well-received.

A new recording of Enoch Arden and The Castle by the Sea by the actor Christopher Kent and the pianist Gamal Khamis has recently been released by SOMM Recordings, with Kent undertaking editorial revisions to the English text as published in the score of Enoch Arden, in order to restore both Tennyson’s original poem and the precise alignment of word and music. Kent has also provided a new English translation of Uhland’s poem with the aim of clarifying the identification of the two speakers whose conversation forms the poetic narrative.

Tennyson’s Enoch Arden and other Poems was a publishing sensation when it appeared in 1864, selling 17,000 copies on the day of publication and 60,000 before the end of that year. The story that Tennyson tells crosses Homer’s Odyssey with Robinson Crusoe. Essentially, a sailor is shipwrecked, survives on a desert island, is rescued, and returns home to find that his wife has remarried his former friend. Tennyson’s detailed elaboration is ostensibly a paradigm of Victorian sappiness but – ironically, given that the volume as advertised as ‘Idylls of the Hearth’ and the eponymous sailor’s departing words to his wife are, “Keep a clean hearth and a clear fire for me,/ For I’ll be back, my girl, before you know it” – the poem presents a covert and ultimately unresolved tension, issuing a challenge to patriarchal mastery and the gendered sanctity of the home with its representation of inadvertent and unacknowledged bigamy and illegitimacy, which remain concealed as a result of the self-sacrificing silence of the protagonist.

In a small unnamed English seaside town, ‘a hundred years ago’, three children – Annie Lee, Philip Ray and Enoch Arden – play at ‘keeping house’. Philip suggests that they should take turns to be Annie’s husband’, thereby foreshadowing both the feelings that the two men as adults will have for Annie and future turns of fate. Annie marries Enoch, and they have three children, but an accident and hard times lead Enoch to seek to restore their fortunes by joining a ship bound for China. When he is absent, his sickly youngest child dies. The unmarried Philip provides solace and support, but it is ten years before he can persuade Annie that Enoch has perished. She finally agrees to marry Philip and they have a child of their own. Enoch is not in fact dead, however; he has been shipwrecked, alone, on a tropical island. Eventually he is rescued but when, upon returning home, he sees the happy family group, he vows not to speak to Annie. Barely a year later he falls ill and reveals his story to his landlady, asking her to convey his blessings after his death to Annie, Philip and his children.

If critics have been inclined to view Strauss’s two melodramas as insignificant or ‘slight’ works, one explanation may be that the genre is viewed either as song without singing or drama without staging, innately ‘lacking’ some essential quality of the respective medium. Moreover, Strauss’s score offers little more than fifteen minutes of music in recitation lasting more than an hour. But, Kent and Khamis skilfully show how the words and music do more than sit side-by-side, with the piano simply commenting on the action; instead, they work together in subtle ways to communicate the poem’s direct and covert meanings.

Kent’s speaking voice is judiciously modulated, sensitive to the rhythm and phrasing, teasing out details and crafting the emotional curves of the drama – as fortunes rise and fall – but never exaggerated. Characters’ words are gently individualised within the flowing narration. Khamis’s entrances and retreats feel natural and intuitive. Moments such as the death of Enoch’s child are tenderly sketched, avoiding mawkishness, while a delicate wistfulness, à la Rosenkavalier, imbues the trance-like visions and echoes that haunt the shipwrecked Enoch, and forms his musical epitaph. Voice and piano are well-balanced too, the music never overpowering the spoken word even in the more exuberant episodes, such as the resounding clarion which accompanies the jubilant marriage of Philip and Annie – a ‘pealing of [his] parish bells’ which Enoch seems to hear, faintly, in terrible ignorance, alone on his distant island.

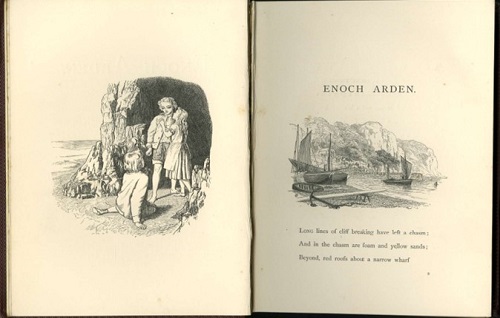

Strauss’s score for Enoch Arden has been described by some critic as ‘scanty’ and insignificant, but perhaps the sparseness of the musical contribution only deepens the import of the musical utterance, the un-silencing of the music adding to the meaning of the particular episodes and moments that Strauss chooses to complement or develop in powerfully expressive ways. Tennyson’s ekphrastic poem is dense with detailed imagery; indeed, its picturesque set-pieces have made Enoch Arden attractive to illustrators. There are several illustrated editions, and Julia Margaret Cameron produced three photographs depicting the characters in the early parts of the poem. Strauss’s music, however, does not set out to enhance Tennyson’s idyllic pictorialism. Instead, Strauss employs a leitmotivic method which seems fitting given the patterning and repetitions which are such a significant feature of the poem, parallels of place and situation being reinforced by literal verbal repetitions. It is not the external world but the inner life which Strauss’s music for the piano divulges and elaborates, giving expression to the unknown, unsaid and suppressed.

This dramatic tension is evident from the first. Enoch Arden begins with a storm-tossed sea, surging, arching scales in the piano left-hand, with rocking chords hovering precariously above, framing the opening description of the unidentified seaport which is the geographical location of the poem. Khamis tames the turbulence, bringing the rocking gently to rest, and when Kent commences the narration, it is with the relaxed breadth and neutrality of the natural storyteller, establishing the vista before us: the chasm in the long lines of cliff, the red roofs beyond clustered about ‘a narrow wharf’:

then a mouldered church; and higher

A long street climbs to one tall-tower’d mill;

And high in heaven behind it a gray down

With Danish barrows; and a hazelwood,

By autumn nutters haunted, flourishes

Green in a cuplike hollow of the down.

The agitation and imminence of the music is in stark contrast to the still detachment of the scene, although perhaps the crumbling of the cliff, foaming chasm and the mouldering of the church presage disintegration. For, the piano’s tumult is a portent of storms, literal and figurative, to come. The music of the sea-storm will return in the second part of the melodrama when Enoch is shipwrecked but it also symbolises the currents which destabilise the idyllic image of Annie, “the prettiest little damsel in the port”, Philip, a prosperous miller’s son, and Enoch Arden, a “rough sailor’s lad”, as they play peacefully amid “the waste and lumber of the shore” – an image which Strauss accompanies with carefree gambolling when Annie reconciles the quarrelling lads, promising that “she would be a little wife to them both”.

Kent and Khamis sensitively pace and shape the dynamic between word and music to reveal the meaning that lies in the space between the two. When, in the hazelwood’s hollow, Enoch proposes to Annie, Kent intensifies the description of Enoch’s face, his ‘large gray eyes … [a]ll kindled by a still and sacred fire,/ That burned upon an altar’. But, it is through Philip’s eyes that we look here, as he approaches the enraptured pair, and it is his creeping retreat that the piano delineates, the darkness of the descent drawing the colour and animation from Kent’s voice. While the nutters continue their merry-making, Philip’s “dark hour” remains “unseen” but Strauss ensures that his suffering – “a lifelong hunger” that he will carry in his heart – is not unheard.

Similarly, on the eve of Enoch’s departure, Annie’s fearful premonition – “O Enoch, you are wise:/ And yet for all your wisdom well know I/ That I shall look upon your face no more.” – is made ominously sombre by the entry of the piano’s slow chordal reflections, and this general enhancement of the grave mood is expanded in the piano interlude which follows to hint at a future of which Annie herself is unaware, the return of the rushing scales of the storm punctuated by the motif associated not with Enoch but with Philip, even though the latter is far from her thoughts and indeed absent from the narrative at this point in the poem. Such musical intimations are reversed when, ten years later, Philip accompanies Annie and the children into the hazelwood and they rest in the hollow which was the scene of the earlier, wounding proposal of marriage. Now, Philip’s pleading – “‘The ship was lost’ he said ‘the ship was lost!’” – is unsettled by echoes of Enoch’s low twisting motif, its angularity discerningly sculpted by Khamis, a discomforting confirmation that Philip’s reassurances, so earnestly delivered by Kent – “‘It is beyond all hope, against all chance,/ That he who left you ten long years ago/ Should still be living’” – are false.

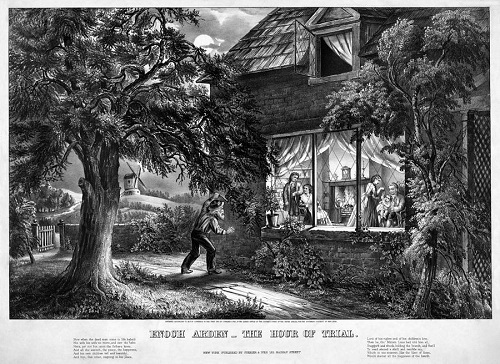

The most intense of such tableaux is the scene when Enoch, peering through the window of Philip’s house, sees his family again after his long absence and understands that he has been supplanted by his childhood rival:

[C]ups and silver on the burnished board

Sparkled and shone; so genial was the hearth:

And on the right hand of the hearth he saw

Philip, the slighted suitor of old times,

Stout, rosy, with his babe across his knees;

[…]

And on the left side of the hearth he saw

The mother glancing often toward her babe,

But turning now and then to speak with him,

Her son, who stood beside her tall and strong,

And saying that which pleased him, for he smiled.

No music accompanies this sentimental set-piece, which Kent imbues with a slight intensity, tightening the rhythm of the phrases, the observations seeming coloured by a tint of bitterness. But, Khamis’s growling agitations intrude as Enoch absorbs the reality before him, and its emotional consequences, Kent masterfully controlling the escalation from shock and anger, through physical disorientation to spiritual anguish. Interestingly, the voice of the narrator and of Enoch seem to fuse at this point, allowing us to experience the full force of Enoch’s desolation as he understands the silence that he must keep:

Uphold me, Father, in my loneliness

A little longer! aid me, give me strength

Not to tell her, never to let her know.

Help me not to break in upon her peace.

My children too! must I not speak to these?

As Enoch makes his way home, the piano’s low pedal draws Enoch down into a bottom-less weariness, as the circling repetitions in the right hand embody the stagnation of his stoicism: “As tho’ it were the burthen of a song,/ ‘Not to tell her, never to let her know.’” Here, a rare intervention by Kent, who repeats the dreadful negation, “Never”, painful underscores the infinite nature of Enoch’s suffering – a suffering which the twilight harmonies of the piano’s postlude softly salve, but cannot cure.

In the final section of the melodrama Enoch tells his landlady, Miriam Lane, the story of his life, a story which she is made to swear “sternly on the book” not to reveal until after his death. We do not hear the words of Enoch’s story; the narrator merely reports that it was told. But, on his deathbed, Enoch commands Miriam to tell Annie that “‘I died/ Blessing her, praying for her, loving her’”. Kent powerfully communicates the terrible burden of Enoch’s sacrifice, and the return of the narrative voice and the abrupt nature of the ending are an almost shocking wrench away from Enoch’s consciousness. For, Tennyson’s poem closes with three lines:

So past the strong heroic soul away.

And when they buried him the little port

Had seldom seen a costlier funeral.

The temporal fluidity of the piano’s delayed resolutions – music which recalls the moment on the island when he finds solace through communion with God, and when he resolves to keep secret his return – may suggest the spiritual transfiguration intimated by Enoch’s dying vision, “‘a sail! a sail!/ I am saved’”, but it’s a discomforting conclusion, which Kent subtly underscores. For, Enoch’s blessing bestows upon Annie and Philip a knowledge which burdens their union and their family with the taint of illegitimacy and sin. Enoch’s passive heroism may be sanctified but it is not without consequences. Kent’s slight separation of the final two words, “costlier … funeral”, underlines this tension and emphasises, too, that the funeral was only possible because of Annie’s marriage to the wealthy Philip, a marriage which Enoch’s blessing exposes as bogus. The ending of the poem is thus not really an ending at all, but a potentially disruptive and tragic beginning.

The Castle by the Sea concludes the recording, and presents a more convention dialogue between words and music, Strauss’s music largely serving to enhance the pictorial and aural imagery – the castle “With gold red clouds above it/ In gorgeous pageantry”; the dimly shining moon and gloomily hanging mists; the ocean with “majestic wings” that “sing out”. A “deep lament” is heard from within the castle hall, stirring tears in one of the speakers. Kent and Khamal capture the moody impressionism of the scene, building a shapely dramatic arc while retaining the enigmatic elusiveness of Uhland’s poem. Kent’s delivery is, fittingly, more mannered here, with dramatic pauses and emphases, his voice animated by a certain ominousness, while Khamis finds both radiance and shadows in the piano’s atmospheric meanderings.

This is a really thought-provoking and riveting disc. The recorded sound is immediate but not overly resonant, creating an embracing space into which to settle into the unfolding drama of Enoch Arden. Together, Kent and Khamis present an intimate, engaging piece of chamber music which holds the listener’s attention throughout. If you like a good story, you’ll be entranced.

Enoch Arden and The Castle by the Sea is available from SOMM Recordings.

Claire Seymour

Richard Strauss: Enoch Arden Op.38 TrV181, The Castle by the Sea, TrV191.

Christopher Kent (actor), Gamal Khamis (piano)

SOMM CD 0651 [69:45]

ABOVE: ‘Enoch Arden’, George Goodwin Kilburne