In 1951, the English Opera Group commissioned a work from Lennox Berkeley, to be performed at the fifth Aldeburgh Festival the following year. That work, the Variations on a Hymn by Orlando Gibbons Op.35 for tenor soloist, SATB choir, organ and string orchestra, was duly performed at the 1952 Festival by tenor Peter Pears, organist Ralph Downes and the Aldeburgh Festival Choir and Orchestra conducted by Berkeley himself, in Aldeburgh parish church. It then languished unheard, though it was published by Chester’s in 1981.

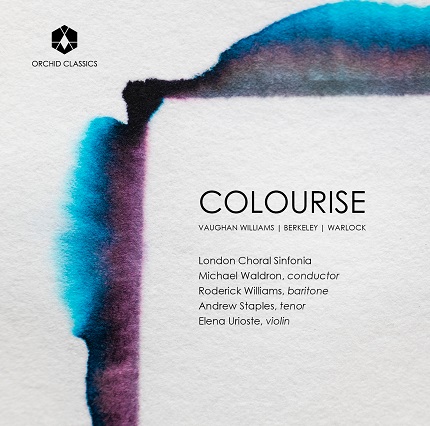

A chance encounter with the score by Michael Waldron, founder and Artistic Director of London Choral Sinfonia, has inspired Colourise, recently released by Orchid Classics, which brings together works for voices and strings by English composers of the early twentieth century. Pastoral birdsong, Jacobean hymnody, meditative poetry and French Renaissance dance: such are the evocative hues that run through and bind the varied works which converse with and draw inspiration from the cultural past.

Berkeley came across Gibbons’ theme in the Yattendon Hymnal which had been published by Robert Bridges and Harry Ellis Wooldridge in 1899. Therein it set ‘My Lord, My Life, My Love’, text based on verses from Isaac Watts’ 1715 collection for children, where it was titled ‘Praise for Creation and Providence’. Gibbons’ melody and bass lines – setting the words of the hymn, ‘Lord I will sing to thee / for thou displeased wast’ – had originally been published in 1623 in The Hymnes and Songs of the Church, a two-part collection of 90 ‘songs’ of which music, by Gibbons, is extant for just seventeen.

Gibbons’ theme is first heard in the opening bars played by a solo quartet whose vibrato-less tone has a slightly viol-like grain. Berkeley’s lyrical impulse is very evident here, along with his sharp ear for a telling tonal nuance: there are some piquant dissonances which draw on the false relationships in the original and which generate a surprisingly rich full-string flowering, urgent above low pedal notes. The fragmentation and variation of the theme is inventive, small motifs developing with contrapuntal clarity and textural freshness. Contrasts are striking. Scalic figures that climb tentatively suddenly erupt in vocal elation, the singers relishing the vigour of the lines, the strings matching their dynamism, the organ swelling the magnitude. The sound quality is superb and the dexterity of both the compositional conversations and their delivery, as well as the diversity of vocal and string colours, is crystal clear.

Andrew Staples is the tenor soloist and to him is accorded the text of the third verse of the hymn, “To thee in very heaven/ The angels owe their bliss”, from which Staples draws out the ecstatic quality. Melismas, “Where perfect pleasure is”, provide surprising harmonic aches, but Staples preserves the lyricism however angular the twists and turns. Repetitions (“very heaven”, “the angels”) evoke spiritual fulfilment, especially when the tenor’s strong, clear tone lightens and a beautiful head-voice high A floats heavenward. Such spiritual feeling is taken up by the organ, introducing an assertive choral episode, “And how shall man, thy child,/ Without thee happy be”, which pulses richly with accented string interjections and Britten-esque vocal writing.

There are contrasting sombre episodes, as when Berkeley uses the quiet strings to develop the minor third which characterises the second phrase of Gibbons’ theme, or the twisting false relation of the third. But, it is with jubilation that the variations conclude with the choral praise, “Return my Love, my Life”, above which Staples is an ardent cantor. The spiritual joy calms with the tenor’s eloquent repetitions of the opening line, “My Lord, my Life, my Love,/ To thee I call”, a minor sixth rise to a poignant dissonance seeming to striving for a resolution which at last comes in a calm cadence of consonance and peace. It’s a superb performance of a deeply expressive work, and a reminder that sadly Berkeley’s discography is not large. Colourise is worthy buying for this work alone.

But, there is much more to enjoy here. Vaughan Williams’ Five Mystical Songs also look back to the seventeenth-century – to George Herbert’s The Temple, an extended meditation on man’s relationship to God from which the agnostic Vaughan Williams sets four texts (the two parts of ‘Easter’ forming the first and second songs). There are several scorings of the cycle, the original version for baritone and piano having been revised for baritone, chorus and orchestra when it was premiered at the Three Choirs Festival in Worcester Cathedral in 1911. There’s also an adaptation for wind but this is the first recording of the version for soloist, chorus, string orchestra and piano.

In her biography of her husband, Ursula Vaughan Williams wrote that – despite the composer’s agnosticism – ‘he was able, all through his life, to set to music words in the accepted terms of Christian revelation as if they meant to him what they must have meant to George Herbert or to Bunyan’. There’s certainly a directness about the setting of the text, nowhere more so than in the first song ‘Easter’ which opens with Roderick Williams’ fervent declaration, “Rise heart, the Lord is risen”, the ardent resonance spilling into the choral completion of the phrase. It’s a terrifically dynamic open, and Williams and Waldron capture the almost Elgarian nobility and certainty of the song.

Indeed, it’s interesting that Vaughan Williams’ words about the music and so called ‘mysticism’ of Holst seem embodied in his own writing here: ‘[it] has pre-eminently that quality which for want of a better word we call “mystical”, and this in spite of the fact that it was never vague or meandering … It is perhaps this very clarity which gives the “mystical” quality to his music. It burns like a clear flame for ever hovering on the “frontier to eyes invisible”.’ The flame burns bright in this movement, stoked by the serene sheen of the high violins and the piano’s throbbing triplet pulses within the string texture. Waldron expertly controls the ebb and flow of the tempo, and Williams’ phrases extended naturally and easily, each and every word making its mark. The balancing of his focused vocal line with the much quieter chorus and strings in the closing episode is perfectly judged.

‘I Got Me Flowers’ begins with piano alone, the increasing repetitions urging in the solo voice. It’s hard to imagine the melismas gliding with more sweetness, and Waldron complements Williams’ tender phrases with gently shifting changes of metre and reflective modal tints. With the modulation to the major mode, the quiet humming of the chorus is a mellifluous support to Williams’ melody, the baritone also softening his tone, “We count three hundred, but we misse”, though I challenge the listener not to quake, and delight, at the ensuing thunderous declaration of faith: “There is but one, and that one ever.”

There’s some expressive muted string meandering in ‘Love Bade Me Welcome’, and the final section is heart-achingly beautiful, the piano’s quiet rocking supporting soft but full choral vocalise and delicate solo string interjections that recall the quiet contemplation of The Lark Ascending. As always Williams’ attention and response to the details of the textual and musical phrase are exemplary, “I the unkind, ungrateful? Ah my dear, I cannot look on thee” subsiding from palpably burning pain to exquisitely tender pathos. ‘The Call’ acquires a beguiling lilt, before joy slips into mystery, while the ‘Antiphon’ surges and sparkles in organ-like splendour.

To supplement the nod to this year’s Vaughan Williams’ anniversary, we have The Lark Ascending itself, too, in the arrangement by Paul Drayton for violin and mixed choir (2018), which was commissioned by the Swedish Radio Choir and conductor Simon Phipps and premiered by them in 2019. Drayton preserves the solo part, performed here with unsentimental clarity and eloquence by Elena Urioste, and adapts for mixed choir the twelve lines of George Meredith’s poem that Vaughan Williams drew upon in the folksong–like middle section. Initially it flows with the relaxed simplicity and smoothness of the most comforting folksong, but grows in complexity as solo voices converse with the solo violin, flying up, dipping down, circling, swirling, surfing the air. Elsewhere the wordless choral bed of sound is expertly sustained and blended. Waldron knows when to encourage warmth and expansion to support the violin’s soaring explorations and his singers respond to every detail of his direction, swelling at times with magnificent sumptuousness but never forcing the sound, while vocal solos glide easily through the texture.

Warlock’s Capriol Suite completes the programme. This is simply lovely playing from the LCS strings – every ounce of their enjoyment sings through Warlock’s dances. The Basse-Dance and Tordion are delightfully crisp and light, accents judiciously placed and weighted – I love the wry dryness of the pizzicato episode in the latter. ‘Pavane’ is perfectly paced, fluid and graceful, while Bransles scampers with a sprightly mischief. The Pieds-en-l’air soothes with velvety spaciousness, and the swords of Mattachins clash with highly coloured vigour.

Colourings is Orchid Classics 200th release and it’s one of which they – and all the participants – should be very proud. Buy it for the Berkeley but savour the rest of its musical offerings which open up a much-needed space for contemplation, calm and peace of mind.

Claire Seymour

COLOURISE: Roderick Williams (baritone), Andrew Staples (tenor), Elena Urioste (violin), London Choral Sinfonia, Michael Waldron (conductor)

Vaughan Williams – Five Mystical Songs (world premiere recording: version for strings and piano); Lennox Berkeley – Variations on a Hymn by Orlando Gibbons Op.35 (world premiere recording); Warlock – Capriol Suite; Vaughan Williams – The Lark Ascending (arranged by Paul Drayton)

ORC100200 [63:57]