In Mozart’s Operas: a critical study (1913), Edward J. Dent pronounced Lucio Silla to be ‘a frigid piece of formality’ and ‘a mediocre opera, not even as good as Mitridate’. Laurence Equilbey, in the Conductor’s Note to this live recording of the sixteen-year-old Mozart’s opera seria, declares the composer to have shaken up the conventions of the genre, conveying ‘the passions and torments of the human soul, its challenges and anguish, all with profound intensity yet at the same time with infinite grace, agility and lightness of touch’. They can’t both be correct. So, which is it: neglected gem or adolescent note-spinning?

Well, the answer is probably neither. The libretto, by Giovanni de Gamerra (with some prudent tidying up by Metastasio) is routine seria sententiousness, with a dubious volte face at the close by which the eponymous narcissistic dictator becomes a model of Enlightenment virtue. A sub-plot – necessary to provide Mozart’s star singers with their required show-piece arias – hinders the dramatic development of the second Act (though much of that is cut here). Equilbey removes the minor role of Aufidio, Emperor Lucio Silla’s friend and tribune, and also cuts arias and omits or shortens quite a few of the secco and many lengthy orchestrated recitatives, professing to have retained those which are ‘strictly necessary for the narrative’. Quite a lot is missing.

On the plus side, though, Mozart’s score shows that the teenager had already developed the ability to write with dramatic and psychological insight for the voice, and the rich details of the score are often surprisingly bold, with unexpected harmonic modulations, interesting textural details and imaginative interplay between the voices and instruments. The arias mostly follow the long da capo format, though Mozart begins to experiment with some more concise forms, as well as ensembles, and at times there is fluid movement between the expressive accompagnato recitatives, arias and instrumental interludes. Some splendid creativity and innovation, then, within the boundaries of the genre. Idomeneo is on the horizon.

Lucio Silla was the last of the commissions that Mozart received in Italy, during the fifteen-month tour of the length and breadth of the country that he undertook with his father at the start of the 1770s. It followed the premiere of Mozart’s first opera seria, Mitridate, re di Ponto, in Milan’s Teatro Regio Ducale on 26 December 1770, the success of which encouraged the ducal theatre to commission a second opera from Mozart to open the 1772-73 Carnival season. The contract for Lucio Silla was signed on 4 March 1771, which Grove notes required Mozart to deliver the recitatives in October 1772 and to be in Milan by November to compose the arias and rehearse ‘with the usual reservations in case of theatrical misfortunes and Princely interventions (which God forbid)’.

There were, inevitably, some ‘misfortunes’. Metastasio’s interference in the libretto necessitated some re-writing of the recitatives, and illness forced the tenor Cordoni, for whom the title role was conceived, to withdraw. On 5th December 1772, Leopold Mozart wrote to his wife in Salzburg that ‘the theatre secretary has been sent to Turin by special post-chaise and a courier to Bologna to find another good tenor, who must not only be a good singer but, more especially, a good actor with a fine presence in order to play the part of Lucio Silla with distinction. Given the fact that the prima donna arrived only yesterday and the tenor still isn’t known, you’ll easily appreciate that the bulk of the opera and, indeed, the main part of it hasn’t been written yet’.

The replacement tenor, Bassano Morgano, was signed up only a week before opening night and was, in Leopold’s words (2nd January 1773), ‘a church singer from Lodi and had never performed in such a prestigious theatre’. His acting left something to be desired, too: ‘He has to gesture angrily at the prima donna in her first aria, but his gesture was so exaggerated that it looked as if he was going to box her ears and knock off her nose with his fist, causing the audience to laugh.’ Consequently, Mozart composed only two arias, rather than the four prescribed by the libretto, for his titular Emperor.

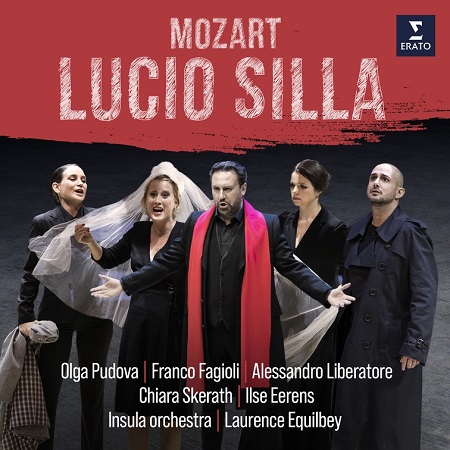

The first performance, on 26th December, was also afflicted by mishaps. The start was delayed by three hours because Archduke Ferdinand was writing his New Year letters, and the performance was immensely long – there were three ballets – not finishing until 2 o’clock in the morning. Subsequent performances were well-received, though, but after its 26-performance run in Milan Lucio Silla was not staged again in Mozart’s lifetime. Its first modern revival took place in Prague in 1929 and it was staged in 1964 in Salzburg. The first UK performances took place in March 1967 in St Pancras Town Hall, conducted by Charles Farncombe, in a new English translation by Andrew Porter. This live recording has its origins in a 2016 European tour that Equilbey undertook with her period-instrument Insula orchestra. The five soloists and director Rita Cosentino re-gathered to revive the production in 2021 at the Festival Mozart Maximum (which Equilbey founded) and this disc was recorded live in La Seine Musicale in Paris in June that year.

The libretto draws on events during the reign of the Emperor Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix (138-78 BCE). With the aid of his sister, Celia, the eponymous Roman dictator tries to win the heart of Giunia – daughter of a murdered senator, Silla’s enemy, Gaius Marius – wooing with a mixture of romance and threats. Giunia believes her exiled fiancé, Cecilio, to be dead but the latter is very much alive and has returned to Rome. They are reunited by the tomb of Giunia’s father, where she goes to weep and pray at night. Silla promises Celia that if his suit is successful, she can wed Lucio Cinna, Cecilio’s friend. Various assassination plans are mooted, while Giunia enrages Silla by repeatedly refusing to wed him – she would rather die. And, it looks as if the beloveds might find comfort only in a shared death. But, when Cecilio is brought before the Senate, Silla astonishes everyone by pardoning him and Cinna, and offering them their respective brides. He then renounces public life and is praised by all for his magnanimity.

Equilbey draws a light, bright sound from her players. Tempos are brisk, but not too much so. The three-movement overture begins with springy string playing, and punchy woodwinds and horns. Dynamics are neatly terraced. And, in the contrasting, gentle second theme, trills and staccatos from flute and violins dance delicately. A sweet-toned Andante is followed by a triple-time Allegro characterised by airy, clean textures. Many of the arias have long ritornellos and Equilbey treats these affectionately and with detailed expression. The first two arias set the high benchmark: Cinna’s first aria is preceded by crisp running scales for the strings answered by lovely colours from oboes and horns, and there’s a real sense of a conversation between the instruments throughout – they are not ‘just’ accompanying. The aria for Cecilio that follows also has some smashing oboe and horn interjections – there’s a lot going on in the score, but the result is a model of clarity.

The truncation of the Roman Emperor’s role throws the spotlight on Cecilio and Giunia. The first Cecilio was the male soprano Venanzio Rauzzini (for whom Mozart also composed the motet Exsultate, jubilate) but modern recordings have favoured female singers: Leopold Hager’s mid-1970s recording for Deutsche Grammophon disc had Julia Varady in the role; Cecilia Bartoli sang for Nikolaus Harnoncourt’s 1989 Teldec disc, recorded live in Vienna. Equilbey plumps for countertenor Franco Fagioli, a singer whose performances I’ve sometimes found impressive from a technical point of view but tonally shrill and verging on the hysterical dramatically. There’s much to admire here though, particularly in the accompanied recitatives which Fagioli imbues with considerable expressive sentiment, often supported by some very sympathetic string playing. He works hard to establish a compelling psychological portrait. When Cecilio is waiting at the tomb for Giunia’s arrival there is palpable emotion, and real tenderness, in Fagioli’s voice; in contrast, his fury is in no doubt at the start of Act 2 when he is planning Silla’s assassination, and here the fierce string semiquavers really prickle with urgency.

Leopold Mozart described (28th November 1772) Rauzzini singing his first aria, ‘Il tenero momento’, ‘like an angel’. Fagioli is not so celestial, but his coloratura divisions are very secure and he certainly can execute a confident trill. I find the change of colour between registers rather disconcerting though – the part incorporates octave-plus leaps and encompasses two octaves – for it makes Cecilio sound not just determined but a little deranged. And, while those top As are rock solid they don’t always sound very pleasing. Cadenzas are extravagant too, though perhaps that’s ‘authentic’. Fagioli loses his Act 2 aria, ‘Ah se a morir mi chiama’, but Act 3’s ‘Pupille amate’ offers a chance for simplicity to shine – it’s a lovely ternary form song. Here, though, I find the portamentos and ornaments a bit fussy; I’d like more purity and less affekt – the music can speak for itself.

The Russian soprano Olga Pudova is excellent as Giunia. ‘Dalla sponda tenebrosa’, her opening aria in Act 1, glows with Eb- warmth and there is real nobility in the orchestral support for her yearning for her father and beloved. In the ensuing Allegro we really feel her rage at the barbarian’s tyranny – strings quiver and accents stab – and some stunningly deft vocal triplets effect another shift of gear into a concluding section of agitation and anguish. The varied episodes which form the famous catacomb scene are well-shaped by Equilbey, and Pudova and Fagioli blend their close thirds sweetly in the long lyrical lines of their duet, ‘D’Elisio in sen m’attendi’, evoking the thrill of reunion and rapture; perhaps it’s not too fanciful to imagine that one hears strains of the Così love duets to come.

It’s worth buying the disc simply to hear Pudova sing ‘Ah me si crudel’: her breath control is absolutely superb – how does she make the lunatic divisions sound anything but demented, and how does she have the stamina to execute such an extravagant cadenza at the close, after all those streams of notes? There’s some nifty violin playing here, too. Then, the recitative, ‘In un istante oh come’, is beautifully expressive, the strings ably supporting Giunia’s very dramatic vows to go to Senate and plead for husband even if the outcome is death. This feels like very mature Mozart, and it’s a pity that the subsequent aria, ‘Parto m’affretto’, is omitted and we launch straight into the later chorus. But, we have Act 3’s ‘Fra i pensier piu fenestra di morte’, in which dark shadows imbue the rhythms and harmonies with intense feeling.

As Cinna, the Swiss soprano Chiara Skeneth displays elegant phrasing, a very pleasing tone and impressively accurate coloratura. She also injects a real urgency into her voice, conveying character, and has a strong lower register, too. When Cinna vows to do his own avenging in Act 2’s ‘Nel fortunato istante’, she easily finds her way around the difficulties and unexpected harmonies, even though Mozart’s accompaniment – sudden contrasts of dynamic and unison interjections – does not offer much help here. ‘Dei piu superbi cor’ is impressively agile.

Celia’s arias are a bit ‘adrift’ given the removal of so much recitative. Why is she singing of ‘parched fields’ and ‘summer’s rain’ in Act 2’s ‘Quando sugl’arsi campi’? And, it’s anyone’s guess why she reflects on storms that rage and stars that are unkind in Act 3’s ‘Strider sento la procella’. But, the Belgian soprano Ilse Eerens sings both arias beautifully (she loses her second aria ‘Se il labbro timido’), and demonstrates the ability to both phrase smoothly, with nice appoggiaturas which convey calm, and to skip through high staccatos cleanly and precisely.

Alessandro Liberatore is an agitated Lucio Silla. His tenor is warm, but it takes him a little while to settle – the pitch is not always absolutely centred in his first aria, ‘Il desio di vendetta’, and he’s sometimes a bit taxed at the top. But, Silla’s ‘D’ogni pietà mi spoglio’ in Act 2 conjures the Emperor’s unstable vacillations between rage and love and in the Trio for Silla, Cecilio and Giunia which closes the Act, Liberatore sings with strength and dramatic focus, the contrasting characterisations making for a tremendously exciting conclusion to the Act. And, the recitative in which vengeance gives way to benevolence is as persuasive as such an abrupt personality change can be, underpinned by some fine pointing of Mozart’s interesting harmonic paths by Equilbey. Le Jeune Choeur de Paris bring proceedings to a reassuring close, with Equilbey drawing characteristically sprightly playing and singing from all.

The booklet includes the aforementioned Conductor’s Note, and a brief discussion between the musicologists Florence Badol-Bertrand and Blandine Berthelot which was planned as an essay by Badol-Bertrand, before her sad death in 2020. There’s a synopsis and libretto texts in French, English and German, as well as colour photographs of the staged production.

I can’t think of any reason why one wouldn’t buy and enjoy this disc, though it’s a pity that the cuts – perhaps necessary in the theatre – are so extensive. At times it feels like highlights, but those highlights are really very good.

Claire Seymour

Mozart: Lucio Silla

Giunia – Olga Pudova, Cecilio – Franco Fagioli, Lucio Silla – Alessandro Liberatore, Lucio Cinna – Chiara Skerath, Celia – Ilse Eerens; Conductor – Laurence Equilbey, Le Jeune Choeur de Paris, Insula orchestra.

Erato/Warner Classics 9029637734 [2 CDs: 64:11, 62:22]

ABOVE: Laurence Equilbey © Julien Benhamou