‘The Only Path’. So reads the insignia emblazoned on the drop curtain, as the overture to Alcina strikes up in the Royal Opera House pit at the start of Richard Jones’s new production of Handel’s opera. Duty, courtesy, mercy and love are the religious and social values upheld by the Puritans who gather during Handel’s French-style stateliness, their motto worn proudly on their chests. But, once the fugal Allegro gets underway there is mischief in the air. For, there is more than one type of love, and Jones presents Handel’s opera as a psychological and emotional tug-of-war between the forces of sacred innocence and earthy sensuality.

So, the sassy arrival of the slinky sorceress Alcina, in sparkly TBD and red-soled Lamboutins, causes a stir, as she flings the Anabaptists’ books of ethics into a garbage bin, bewitches them with a sprinkling of glitter, and whisks them off to her boudoir-island: from Amish to Arcadia. Yet, in the pastoral garden of joy, beauty and romance there is, of course, a serpent. And this snake comes with a meticulously branded image, as the glossy promotional shots of the sorceress and her signature scent attest – a nice nod from Jones to advertising’s illusory promises. When Alcina tires of her entranced lovers, a puff of her eponymous perfume from the ‘urn’ which is the source of her magic power transforms them into birds and beasts – not petrified here, but persuasively animated and prone to reclining, gambolling and dancing courtesy of Sarah Fahie’s quirky choreography.

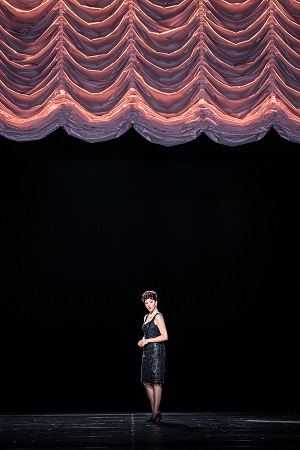

Designer Antony McDonald’s Arcadian landscape both presents the illusions by which Alcina induces her lovers to dare to free themselves from their conventional social mores, and shows us the mechanisms by which she brings about such misconceptions in the eyes of the beholder. For, in reality the island is barren and unkempt, her castle insubstantial and fragile, she herself an ugly hag. Thus, McDonald’s Astro-turf wooded glades slide in and off the stage, as the ruched curtains which frame Alcina’s bedroom rise and fall, the fluidity of movement suggesting a conjurer’s sleight of hand, but also a sort of flimsiness. Lucy Carter’s lighting makes the curtains shimmer and draws out the colour and detail of the menagerie’s beautiful costumes and masks – hare, parrot, goat, King Charles spaniel, turkey, frog, mandrill and many more – but all is contained within a bare black box: Alcina and the island that she conjures are equally hollow.

The da capo arias are enlivened by copious stage business, often involving food: the characters wander about eating plates of oysters, feed rats to huge Venus fly traps, gorge on strawberries. Young Oberto roams in search of his father, Astolfo (currently a magnificently maned lion), his satchel stocked with ‘Missing’ posters. When Oronte, who loves Alcina’s sister, Morgana, causes Ruggiero to suspect he is being deceived and that Alcina has fallen for ‘Ricciardo’ (really Ruggiero’s own wife, Bradamante, disguised as her own brother and also the object of Morgana’s affections), he lines up her wildlife wanderers and forces them to coyly surrender the relics of their romantic encounters: scarves, stockings and suspender belts.

The grassroots rebellion begins in a fertile greenhouse equipped with an array of sharp-pointed gardening tools just right for shattering the scented source of Alcina’s power. (Ironically, the greenhouse is also the site of Morgana’s erotic, and amusing, reunion with Oronte.) Act 1 lays the ground well, and Jones tells the story clearly – which was not always the case in Francesco Micheli’s staging at Glyndebourne this summer – though as we move through the string of arias in Acts 2 and 3, there’s a loss of dramatic tautness. But, what arias they are, and how superbly sung by this cast.

Mary Bevan’s flame-haired Morgan, sporting a diaphanous frock and Doc Martens, was bursting with vivacity and playfulness. Both erupted in Act 1’s ‘Tornami a vagheggiar’ which she kicked off with a lithe leg-scissoring leap which seemed almost to propel her soprano up to glittering heights as the animals celebrated her (deluded) happiness with a dippy but beguiling dance. Bevan was even better in Act 3’s ‘Credete al mio dolore’ in which, having learned that her beloved ‘Ricciardo’ is really Bradamante in disguise, she humbly pleads with Oronte to take her back. Bevan’s control of colour and line was superb, and her sweet tone heart-winning; she was assisted in her charm-spinning by cellist Hetty Snell, who rightly was brought to the stage by conductor Christian Curnyn at the end of the performance.

As Alcina’s lover Ruggiero, the Canadian-American mezzo-soprano Emily D’Angelo had the lion’s share of the work and she paced herself well, building in intensity towards Act 3’s ‘Sta nell’ircana’ – here athletic both choreographically and vocally. Tall and elegant, she convincingly inhabited the besotted knight’s trousers and, later switching to a kilt, both emotionally and physically embodied the opera’s ethos of sexual and psychological ambivalence, persuasively drawing us into Ruggiero’s personal dilemma. ‘Verdi prati’, in which the now-released Ruggiero nostalgically watches the verdant pastures retreat, is the most simple aria in the opera but in some ways it’s also the most emotionally complex and D’Angelo’s rich hues and vocal evenness conveyed her conflicting resignation and regret.

Dressed in lumberjack shirt and combat trousers, Rupert Charlesworth was a vigorous Oronte, tackling his demanding arias with confidence and aplomb, effectively balancing the lyrical and the dramatic, and displaying winning comic nous when making up, or making out, in the greenhouse with Morgana. Franco-Armenian mezzo-soprano Varduhi Abrahamyan was the embodiment of loyal love as Bradamante, but her Act 2 aria, ‘Vorrei vendicarmi’, in which she loses her temper and her patience with the faithless Ruggiero, and which was sung with superb agility and confirmed her strong low register, suggested a chink in Bradamante’s emotional armour. Bolivian bass José Coca Loza was a sure moral centre as Atlante, the leader of the Amish/Puritan community, and as Oberto, the young Rafael Flutter sang with a confidence beyond his years and lovely sweetness and strength.

Which brings us to the titular sorceress. Lisette Oropesa, a favourite at Covent Garden, brilliantly communicated Alcina’s essence and decline: Handel’s enchantress is not ‘evil’, rather a woman who lives by love and yearns to be loved. ‘Di’, corm io, quanto t’amai’ was a creamy expression of a love that we later find out is indeed sincere. The rage of ‘Ah! Ruggiero crudel’ gave way to the pained lament for lost love and power in ‘Ah mio cor’, but Oropesa’s soprano was superbly coloured and controlled whatever sentiments prevailed.

From the pit, there was careful, unfussy support and some fine, comforting theorbo playing (Sergio Bucheli, Eligio Luis Quinteiro) though Curnyn’s tempi sometimes felt ponderous and the instrumental playing never rose to the ‘spirit’ of Jones’s wit and zaniness.

This Alcina ‘Arcadianises’ the Amish but finds that her frail unreality unravels in the face moral righteousness and rectitude. On 5th July 1735 the Universal Spectator, a London newspaper, printed a critique of Handel’s opera – which was premiered at Covent Garden on 16th April 1735, which suggested that ‘the Opera of Alcina affords us a beautiful and instructive Allegory […] The Character of Alcina’s Beauty, and Inconstancy proves the short Duration of all sublunary Enjoyments, which are lost as soon as attain’d’.

Jones has other ideas though. In a final wry twist, the Puritans abandon The Only Way for The Joy of Sex, and Jones’s Alcina becomes, like its eponymous sorceress, a sybaritic celebration of sensual love.

Claire Seymour

Handel: Alcina

Alcina – Lisette Oropesa, Ruggiero – Emily D’Angelo, Morgana – Mary Bevan, Bradamante – Varduhi Abrahamyan, Oronte – Rupert Charlesworth, Atlante – José Coca Loza, Oberto – Rafael Flutter, Dancers – Ashley Bain, Lauren Bridle, Jordan Cork, Sebastien Kapps, Bridget Lappin, Michael Larcombe, Gareth Mole, Ryan Munroe, Luke Murphy, Anthony Pereira, Jay Yule; Director – Richard Jones, Conductor – Christian Curnyn, Designer – Anthony McDonald, Lighting Designer – Lucy Carter, Movement Director and Choreographer – Sarah Fahie, Orchestra of the Royal Opera House.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Thursday 10th November 2022.

ABOVE: ROH Alcina © Marc Brenner