At the end of the seventeenth century, the Parisian publisher Christophe Ballard, in collaboration with his son Jean-Baptiste-Christophe, undertook an ambitious artistic project to publish a new periodical, Recueils d’airs sérieux et à boire, and between 1695 and 1724 many composers – both French and foreign, often anonymous – contributed to this growing collection of thousands of gallant and bacchic airs, some composed for solo voice and continuo, others duets and trios.

François Couperin, organist at Saint-Gervais in Paris since his 18th birthday – a post occupied by his grandfather, uncle and father before him – and recently appointed as an organiste du roi to Louis XIV, contributed seven pieces to Ballard’s collection between 1706 and 1712. These secular songs form part of The Sphere of Intimacy, a recital programme beautifully curated by Christophe Rousset of Couperin’s early music – songs, works for harpsichord and trio sonatas – performed by Rousset with Les Talens Lyriques and the tenor Cyrille Dubois.

Although in the 1690s Couperin had been given a licence to publish his music, only two editions appeared at that time (one of music for organ, the other containing masses). His position at the royal court was prestigious and lucrative, opening up opportunities and renumerations, and he quickly found himself engaged to teach harpsichord to the Duke of Burgundy and several other princes and princesses. Such activities took up time and energy though, and Couperin blamed his royal responsibilities for the tardy appearance of his first book of harpsichord works, which was not published until 1713, by which time he also had the financial wherewithal to pay for the more elaborate engraved collections that he deemed appropriate for his music. Further harpsichord collections followed, along with sacred vocal music (Leçons de tenébres, 1714) and chamber music (Les Goûts-réunis, in 1724, and Les Nations two years later).

These airs sérieux, then, are interesting as they attest to Couperin’s genuine commitment to this secular genre of song – more popular and less sophisticated or elevated in tone than the prevailing airs de cour, but similarly characterised by a simple structure and flowing vocal phrases. Excepting two songs, ‘Qu’on ne me dise plus que c’est the seule absence’ (March 1697) and ‘Doux liens de mon coeur’ (August 1701), Couperin’s contributions were anonymous. However, two of the airs published in 1711 and 1712 respectively, La Pastorelle and Les Pèlerines, appeared in the Premier livre de pièces de clavecin in 1713 (which was prepare for publication in 1710), thereby attesting both to the close relationship between vocal and instrumental melodic style and to the popularity of parody songs, where texts were set to existing instrumental melodies. Manuscript attributions provide some, if less reliable, information about authorship.

Moreover, Ballard’s collections frequently included Italian music, and music which displayed the influence of the Italian style, and so they afford an opportunity to reflect on changing attitudes and tastes among French musicians and their audiences at this time, as they encountered the new sonata, concerto, and cantata idioms. Couperin was among those who immediately saw the creative promise in combining the national styles – a réunion des goûts – and this is reflected in these airs:as he put it when he published Les Nations two decades later, the French and Italian styles and had for a long time ‘shared the Republic of Music France’.

In the opening song on the disc, Les Pèlerines (‘Au Temple de l’Amour’) Cyrille Dubois and Christophe Rousset immediately convey the intimacy of the relationship between Couperin’s vocal and instrumental idioms. Phrasing and ornamentation are perfectly aligned. In the repetitions of phrases and stanzas, decorations are tastefully introduced and graciously executed. Dubois’s tenor is elegant but always expressive: after a graceful, unaffected opening stanza in which the ‘pilgrim maids of Cythera’ present themselves at the temple of Love, the immediate restatement of the text is persuasively heightened – through vocal weight and colour, and textual nuance – introducing a sensuous tint, as flickering ornaments add a frisson of anticipation. Subsequent repetitions subtly turn up the temperature, leading to the slower, triple-time stanza which droops deliciously with the languorous delight which is reflected in the maidens’ eyes. The sweet simplicity of Dubois’s closing phrase, “On lit dans nos yeux les besoins de nos coeurs”, is replete with quiet rapture. Then, the final celebratory stanza trips along lightly and joyfully.

In this simple but charming song, Dubois and Rousset, with artistry and imagination, summon a pastoral idyll. In La Pastorelle (Il faut aimer’), in which Tircis pleads with the shepherdess Iris to ‘seize the day’, for young lovers’ charms do not last forever, they present a mini-drama. Dubois’s tonal palette is both varied and refined. Tircis’s slightly tense mood of anticipation is wonderfully apparent at the start, and there’s a lovely delicate veiling of the vocal line when he insists that secrecy is essential if they are to enjoy their tender love. But, Iris is sometimes fierce in her insistence on steadfastness and discretion – she’s no walkover! Tircis’s reflections on former loves have a beautifully dreaminess, but when he swears his allegiance to Iris the decorations and lightly rising octave leaps bring immediacy to his protestations and avowals – so much so that in the final stanza, as the tempo pulls back, Iris seems to slip into his arms with a silky sigh of acquiescence, “mon coeur m’abandonne”, and Dubois emphasises her submission to passion with a curling appoggiatura, “Tircis, tu triomphes de moi’. Rousset seals her gift, “Cher amant, Iris est à toi”, with a discreet but wry mordant.

Dubois charms the ear with a magic as enticing as Tircis’s courting. We’re back on the isle of Cytherea in Les Solitaires and the tenor glides through the vocal line with light, silvery loveliness as the poet-speaker savours the island’s pleasures and, with intensified tone and tremulous anticipation, lures Sylvie to enjoy delightful days and secret nights. ‘Zéphire, modère en ces lieux’ is more decorative and extended, and the interplay between voice and harpsichord is elaborate, sophisticated but so naturally developed. And, who could not feel Tircis’s anguish in ‘Qu’on ne me dise plus’, so skilfully and movingly does Dubois heighten the verbal opposites and paradoxes – that the absence of Iris, designed to bring a cure for “love’s poison”, is in fact a cruel remedy that makes recovery unattainable? With its biting twists and turns, this is an ‘ayre’ of which Dowland would have been proud.

‘Doux liens de mon coeur’ is a parody setting, a practice that Couperin alludes to in the preface to his third book of harpsichord pieces (1722), praising those ‘famous Poets’ who have ‘done them the honour of parodying them’ and thus contributed to the renown of his music. This air is a parody of an Italian aria for two voices and continuo, ‘Beate mie pene’, which had been circulating in manuscript for some years and had been attributed both to Alessandro Scarlatti and to Charpentier, and which Ballard had published the same year. In his erudite liner notes the French musicologist Denis Herlin suggests that this air testifies to Couperin’s taste for the Italian style, yet the vocal idiom seems to me entirely French in manner – and Dubois’s sweet-toned and natural phrasing make the relished torments of love touchingly palpable.

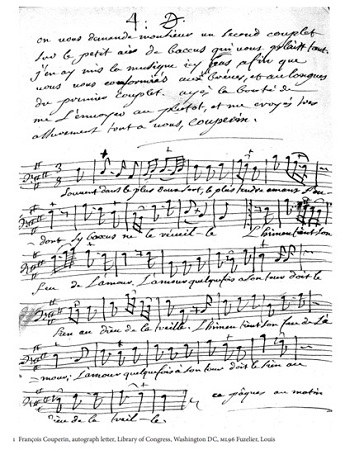

When the Recueils d’airs sérieux et à boire began to be issued, it marked a change from collections that had previously been produced by the Ballard house, and which were discontinued at the end of 1694: the Livres ďairs de différents auteurs, consisting almost entirely of serious airs, and the Recueils de chansonnettes de différents autheurs à deux et trois parties. The new collection was unique in including both airs sérieux and drinking tunes, the latter having usually been published separately. Herlin has written elsewhere about the discovery that he and his colleague Sylvie Bouissou made, during a visit to the Library of Congress in Washington DC, of an autograph letter and drinking song for solo bass by Couperin, ‘Souvent dans le plus doux sort’ – the only extant musical fragment in the composer’s own hand.

The text of the letter reads: ‘You are requested, Sir, to provide a second stanza for the little drinking song that pleases you so much. I have set out the music of it below, so that you may adapt yourself to the longs and shorts of the first stanza. Would you be so kind as to send it to me as soon as possible. Yours most assuredly, Couperin.’ It is dated, simply, ‘This Easter morning’. Herlin has argued convincingly that the note, probably dating from the 1720s, was written to the French playwright Louis Fuzelier, and perhaps indicates a request from Jean-Baptiste Christophe Ballard. ‘Souvent dans le plus doux sort’ wasn’t published in Recueils d’airs sérieux et à boire but it recalls the idiom of ‘Zéphire’. Dubois introduces a slightly nasal quality to his tone at times, pointing the droll reflection that Love sometimes needs to be awoken by Bacchus, the ‘God of the Vine’.

In August 1707, Ballard published the Pièces choisies pour le clavecin de différents auteurs, a collection of short, anonymous pieces grouped by key, some of which are now attributed to Couperin, with others thought to be by Marin Marais and Louis Marchand. As Herlin remarks, the titles (Gavotte italienne, La Florentine, La Vénitienne) indicate an affinity with the Italian style which is confirmed in these lovely miniatures. Rousset’s performances are precise, characterful and refined. I particularly like the Sicilienne (in G), in which the tight trills sparkle, propelled by a robust, rich bass line. La Diane (in D) is muscular and nimble, La Florentine elaborate and intricate (the lines and arguments crisply enunciated by Rousset), while Marchand’s La Vénitienne is proudly florid and confident.

In the 1690s Couperin began work on a set of trio sonatas, which were later published (with different names) in Les nations. La Steinkerque, La sultane (in fact, a sonata en quatuor) and La superbe, are performed here by musicians from Rousset’s Les Talens Lyriques, and once again confirm Couperin’s interest in the Italian style – something he acknowledged in the Preface to Les nations, explaining that, charmed by Corelli’s sonatas, he attempt to compose one himself then passed it off as the work of a new Italian composer, his name formed from an anagram of Couperin’s own. The bright recorded sound makes the instrumental colours and conversations very present; the palette is rich and the dialogues incisive. There’s much to admire, from the expressive intensity of the ‘squeezing’ harmonies of the opening Gravement of La Sultane, to the eloquence of the melodising by violin, oboe and bassoon in the central Très tendrement of La Superbe, to the bristling verve La Steinkerque’s ‘bruits de guerre’.

It’s the airs that really take one’s breath away, though: miniature miracles, magically performed.

Claire Seymour

Cyrille Dubois (tenor), Christophe Rousset (harpsichord & direction), Les Talens Lyriques

François Couperin, The Sphere of Intimacy: Airs sérieux et à boire; Sonatas – La Sultane, La Superbe, La Steinkerque; Pièces choisies pour le clavecin de différents auteurs.

Aparté AP281 [67:00]

ABOVE: Cyrille Dubois