If you thought that fairy tales were for children, then this fantastic – in all senses of the word – double bill at the Royal College of Music would teach you otherwise. It was Angela Carter who reminded us that these tales were not ‘unique one-offs’ but reconfigured by their tellers to form a panoply of variations on a theme, often with very different effects. Director Liam Steel takes that one step further and brings a sleeping beauty and a scolded child together with stunning and disturbing effect.

Respighi’s La bella dormente nel bosco (The sleeping beauty in the wood) began life as a commission from the puppeteer Vittorio Podrecca, whose company first performed it in April 1922, with the singers placed in the pit. It retells the first part of Charles Perrault’s version of the tale of Sleeping Beauty, although this princess sleeps for not 100 but 300 years, awakening in the 20th century, and is thus even more of a living anachronism – the past living in the present.

Michael Pavelka’s ‘set’, inventively lit by Andy Purves, doesn’t bother with specifics, though, choosing to embrace ambiguity: instead, we have skeletal trees in a murky wood swept by woozy mists. Shape-shifting is the stuff of faerie, and Steel and his team take that to heart, puckishly playing with the visuals: croaking, leaping frogs spangle through the gloom; spiders’ webs are electronically spun, silvery threads to guard the sleeping beauty. It’s all gleefully free and imaginative.

And, then there are the puppets. The singers are released from the pit and mingle onstage with puppeteers, their costumes blending realism and toy theatre; and, they often do the puppetry manipulating for themselves, as well as tackling Respighi’s vocal challenges with aplomb. The effect is mesmerising, and the surprises pile up. There’s a surreal Peter Greenway-esque air, and a patina of The Ghost of Versailles’ dust; I kept expecting Helena Bonham Carter to pop up …

Steel in-fills Respighi’s musical prologue. So, we see a young lad playing with his toys, his copy of Sleeping Beauty lying beside him, until his mother interrupts his dreaming, and reality – in the form of an ominous, belt-wielding step-father – sweeps imagination aside. We’ll return to that small child later, but in the meantime Steel and Pavelka let their own imaginations run wild. So, we have gauzy ‘good fairies’, who bestow blessings on the new-born princess, and float and fly, born on the energy of LED light-bulbs – a new take on ‘fairy-lights’. Sofia Kirwan-Baez’s coloratura Blue Fairy is somehow both otherworldly and very present.

And, there’s a banshee green fairy – Eyra Norman’s ferocious Wicked Witch of the West – furious at being excluded from the feast; a spindle that has more animation than its geriatric spinner (Zixin Tang); and a down-to-earth, orange-clad lumberjack (Redmond Sanders), who tells the Prince where to find his sleeping princess. Jamie Woollard is a sturdy King; Lily Mo Browne his Queen.

In the pit, conductor Michael Rosewell makes the eclectic score sound lush and nimble. There’s some Debussy, Stravinsky, Strauss and Massenet here, but the large orchestra – with a prominent part for piano – makes the stylistic medley persuasively apt.

The finale sees Sam Harris’s Prince – his tenor ringing and suave – ‘rescue’ the sleeping princess (a feisty Lylis O’Hara). In Perrault’s tale the prince does not rouse the sleeping princess with a kiss; instead, the narrator attributes her awakening to the ‘end of the enchantment’. The princess’s sassy greeting implies an awareness of the time that has passed, suggesting she was in some state of consciousness long before he arrived, something confirmed a bit later when her superior eloquence is attributed to the fact that ‘she had had the time to think about what she would tell him’.

The narrator asserts, when speculating about the dreams Sleeping Beauty experienced during her hundred-year sleep: ‘it is likely … that during her long sleep the good fairy had seen to it that she enjoyed sweet dreams’. The narrator seems to infer that the princess does not defer pleasure while waiting for her prince, and hints at the erotic nature of that pleasure for when the princess awakens, she looks at the prince ‘with greater tenderness in her eyes than might have been proper for a first meeting’. Her audacious glance suggests a prematurely unrestrained desire.

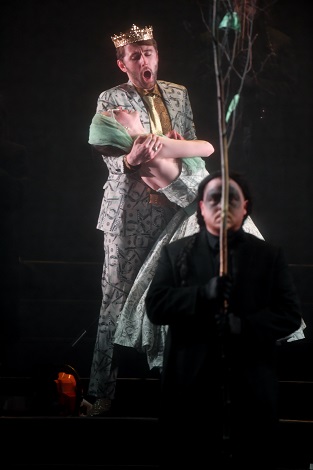

Steel turns Perrault on his head. Though she shares a ‘Wagnerian’ love duet with her liberating hero, this princess is decidedly not pleased to be marshalled into the role – Propp’s ‘prize’? – expected of her, as the marionette’s wires and poles that prod her into subservience confirm. Respighi might end with a Gershwin-esque foxtrot but not everyone is dancing to the same tune in Steel’s conception.

It’s disturbing and dark, and that mood continues in L’enfant et les sortilèges, where the young lad we glimpsed at the start is now found in his 1950s schoolroom – a claustrophobic garret with skylights that let in the eerie glow of the moon – his tantrums the result of neglect and abuse, his mother (Anastasia Koorn) wrapped up with her new husband and inattentive to her child’s need for love.

It’s not all despondency and gloom though. There’s more delightfully inventive shape-shifting as an armchair becomes a yeti formed from the upholstery stuffing (Jamie Woollard), a gloriously anarchic grandfather clock (Daniel Barrett) flaps his pendulum, and a haughty tea-pot turns wrestler (Marcus Swietlicki). Seonwoo Lee’s Fire flames brightly; Dafydd Jones’ arithmetic tutor emerges from the school-desk with frightening fluidity. The metamorphoses are dreamily deft, as is the opening up of the set and the return of Respighi’s eerie forest when the child – a brilliantly judged interpretation by Lexie Moon – encounters the animals who will teach him a lesson in humanity. Respighi’s courtiers reappear. The Child’s final cry, “Maman!”, is heart-breaking.

Claire Seymour

Respighi – La bella dormente nel bosco

La Principessa – Lylis O’Hara, Il Principe – Sam Harris, The Blue Fairy – Sofia Kirwan-Baez, The Old Woman – Zixin Tang, The King – Jamie Woollard, The Woodcutter – Redmond Sanders, The Nightingale – Daniela Popescu, The Cuckoo – Amber Reeves, The Ambassador – Sam Hird, The Queen – Lily Mo Browne, The Duchess – Lucy Gibbs The Fool – Ning Su, The Spindle/ The Green Fairy – Eyra Norman, The Cat – Phoebe Rayner, A Frog – Ceferina Penny, Mr Dollar (spoken) – Connor Dalton

Ravel – L’enfant et les Sortilèges

The Child – Lexie Moon, The Princess – Madeline Boreham, The Fire – Seonwoo Lee, The Nightingale Sofia Kirwan-Baez, The Arithmetic/The Tree Frog – Dafydd Jones, Mother – Anastasia Koorn, The China Cup/The Dragonfly – Charlotte Clapperton, The Bergère/The Owl –Charlotte Kennedy, The Armchair – Jamie Woollard, The Tree – Ross Fettes, The Bat/A Shepherdess – Alysia Hanshaw, A Shepherd – Maria Willis, The Teapot – Marcus Swietlicki

Director – Liam Steel, Conductor – Michael Rosewell, Set and costume designer – Michael Pavelka, Lighting designer – Andy Purves

Britten Theatre, Royal College of Music, South Kensington, London; Wednesday 15th March 2023.

ABOVE: Lexie Moon and Chorus (L’enfant et les Sortilèges) (c) Chris Christodoulou