Over the Whitsun weekend, the Komische Oper in Berlin had something of a Handel festival on with revivals of Barrie Kosky’s production of Handel’s Semele and Stefan Herheim’s production of Handel’s Serse, plus a new production of Saul.

Axel Ranisch’s staging of Handel’s Saul opened on Saturday 27 May 2023 with David Bates conducting. Luca Tittoto was Saul with Rupert Charlesworth as Jonathan, Aryeh Nussbaum Cohen as David, Nadja Mchantaf as Michal and Penny Sofoniadou as Merab. Stage design and videos were by Falko Herold and costumes by Alfred Mayerhofer.

The work was sung in English and was, perhaps inevitably, cut. Bates conducted the Komische Oper orchestra with the addition of Baroque harp, Baroque trumpets and Baroque timpani (duplicating the special low timpani that Handel borrowed from the Tower of London) plus two harpsichords, organ and two theorbos.

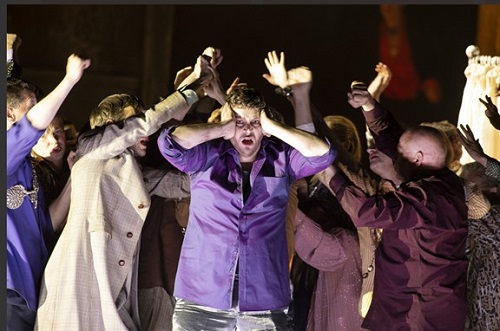

Before the music started, we heard a German voice whispering the plot so far (quite a complex one) to accompany Herold’s vivid animation of the story. The orchestral sound, from the outset, was crisp and vivid, with historically informed string articulations accompanying an equally striking stage picture as the chorus appeared, rejoicing, in multi-coloured clothes (modern with a nod to hippie-chic).

Handel’s oratorios present challenges to any director. Not written for staging, they combine dramatically vivid elements with the more static such as large-scale choruses and, in Saul, the long multi-partite elegy for Jonathan. They also presume on the audience’s familiarity with the subject, there are often gaps in the dramaturgy.

For this production, the dramaturge was Johanna Wall and between them, she and Ranisch, who is a German actor and film director with some operatic experience behind him, had crafted a dramatic narrative that did no real violence to Handel’s work but filled in the gaps. The basic focus was on Saul’s family and the effect on his children of having such a disturbed father. All three siblings were presented as damaged, perhaps brutalised. The relationship between Charlesworth’s Jonathan and Nussbaum Cohen’s David was a gay one, complete with an intense, and of course, logically, this led to a triangular relationship with Mchantaf’s Michal. Not Biblical, certainly, but a logical conclusion to the information Handel and his librettist, Charles Jennens, provide us with.

Less successful was the staging of the choruses. Jubilation and celebration worked fine, but some of the choreography was trite, notably that for the maidens greeting the victorious David, the Envy chorus, with chorus members crowding around David’s bed, came over as creepy and surely it is Saul who is suffering from envy? And the final elegy, heavily truncated, rather overused fake blood and required the dead to come back to life.

The set was fixed, covered in sand, but for most of Act One pride of place went to the humungous head of Goliath with action taking place on, around and in the head. The skull version formed the Witch of Endor’s home. Handel’s oratorio ends with the elegy followed by final jubilation, but at the end of the production, there was a surprise. Nussbaum Cohen remained alone on stage, completely stationary and sang Herbert Howells’ song King David in a lovely RVW-ish orchestration by Iain Farrington. It worked, thanks to Nussbaum Cohen’s mesmerising performance and gave us an ending that emphasised David’s melancholy rather than the Israelites’ triumph.

Italian bass, Luca Tittoto was a magnificent Saul, cutting a handsome figure and singing with an admirably free and focused voice. He roared superbly and gave us a clear picture of Saul’s mental decline. Handel does not give Saul a major aria but it was clear that Tittoto’s singing was very stylish.

His English was somewhat accented, true, but he spat the words out in a wonderfully non-Italian manner, clearly understanding the role that text plays in oratorio.

Aryeh Nussbaum Cohen’s David was not the slight, youthful figure that we might expect, but a strapping lad with a voice to match. Able to conjure moving simplicity in ‘O Lord, whose mercies numberless’, Nussbaum Cohen was admirably vigorous elsewhere, singing with wide-ranging freedom and ease. His diction was not always crisp but overall this was a vivid stage incarnation of the character. And this David was quite a lad, smitten by Charlesworth’s David, he was equally enthusiastic with Mchantaf’s Michal (and Ranisch showed the results with a pregnant Michal at the end of Act Two.

Rupert Charlesworth’s Jonathan was nervous, almost neurotically so, profoundly damaged by his father. His and Nussbaum Cohen’s David began their relationship from the offset, with a coup de foudre, and throughout Charlesworth brought out the way Jonathan was on edge. His declaration of love for David was intense indeed and followed by that kiss and extended make-out session between the two men. Jonathan, however, disappears from Handel’s oratorio in Act Three, alas.

Nadja Mchantaf made a striking Michal, bubbly yet intense and neurotic, needy of affection. She threw herself at Nussbaum Cohen’s David at first sight, well before their marriage, and much of Act One featured Mchantaf, Nussbaum Cohen and Charlesworth in a variety of trilogies. Mchantaf made a fine Handel singer, with her and Nussbaum Cohen as a most enjoyable pairing. As her sister, Merab, Penny Sofoniadou was wonderfully bitchy, yet she softened in Act Two and made a fine foil for her sister.

Ivan Tursic was a vivid Witch of Endor (thankfully played by a man) though he tended to force his tone for dramatic effect. Stephen Bronk’s Samuel was a nicely understated foil to Tursic’s Witch. Tansel Akzeybek, Ferhat Baday and Ferdinand Keller provided sterling support as the High Priest, Doeg and the Amalekite, though I still prefer Barrie Kosky’s solution of combining the High Priest and Doeg into a single role.

A word about the diction; this varied from the wonderfully clear and idiomatic (Rupert Charlesworth was exemplary here) to the occluded and sometimes unintelligible. Inevitable with an international cast perhaps, and we have all been to performances with all-Anglophone casts where diction has been woefully lacking. I was unclear whether this was simply a result of the Komische Oper’s repertory system or whether English remains a somewhat problematic language.

The orchestra was in fine fettle and under Bates’ direction gave us a stylish and vivid account of this, one of Handel’s more richly orchestrated scores. Bates directed from the harpsichord with a second keyboard player, Sabine Erdmann, doubling (tripling) harpsichord, organ and the all-important carillon. The interval was part-way through Act Two and the second half began with a fine account of one of Handel’s organ concertos from Erdmann.

My preference remains for unstaged Handel oratorios, but the team at the Komische Oper created a vivid evening in the theatre, bringing Handel and Jennens’ characters to stage life with style, imagination and not a little daring.

Robert Hugill

Handel: Saul

Saul – Luca Tittoto, David – Aryeh Nussbaum Cohen, Jonathan – Rupert Charlesworth, Michal – Nadja Mchantaf, Merab – Penny Sofoniadou, Witch of Endor – Ivan Tursic, Samuel – Stefan Bronk, High Priest – Tansel Akzeybek, Doeg – Ferhat Baday, Amalekite – Ferdinand Keller; Director – Axel Ranisch, Conductor – David Bates, Stage design & video – Falko Herold, Costumes – Alfred Mayerhofer.

Komische Oper, Berlin; Saturday 27th May 2023.

Photo credit: Barbara Braun