Mozart had already got three operas under his belt – as well as numerous oratorios and masses, symphonies and sonatas – when the fourteen-year-old prodigy was commissioned to compose an opera seria, Mitridate, re di Ponto,for the Regio Ducal Teatro in Milan, for the 1771 Carnival. There were those who had their doubts and those who condemned the work in advance, owing to Mozart’s youth, but when the Milanese audience heard the opera, on 26th December 1770, they were won over – despite its six-hour length (there was a ballet and interpolations of works by other composers). A great success, Mitridate received a further 21 performances. Then, it fell silent until it was revived in Salzburg in 1971.

Mozart set a libretto by Vittorio Amedeo Cigna-Santi after Giuseppe Parini’s translation of Jean Racine’s Mithridate. Set around the Crimean port of Nymphæum in 63 BC, during the conflict between Rome and Pontus, it tells of the military and familial strife of Rome’s deadliest enemy, Mitridate VI, King of Pontus. It has all the required opera seria ingredients: a tyrant king; a ‘good’ son and a ‘bad’ son – half-siblings who are rivals for their father’s betrothed; a jilted mistress; and some violent warmongering. Only some cross-dressing disguises are missing from the mix.

After a long career of expansionist conquest, Mitridate is now at war with Rome. He spreads rumours of his death on the battlefield to test the loyalty of his sons, Farnace and Sifare, and his fiancée Aspasia. Taking advantage of their father’s absence, both declare their love, though Aspasia has feelings only for Sifare. Only the rejected Ismene seems, inexplicably, to see anything of worth in Farnace. When Mitridate returns, all hell breaks loose: the King tries to kill his sons and bride; there are several attempted suicides. Returning from an abortive assault on Rome, defeated and wounded, Mitridate stabs himself to deny his foes the pleasure, but not before forgiving and reuniting all the young lovers, who swear, in a short closing chorus, to resist Rome.

Tim Albery’s new production for Garsington reduces the action to 2 hours 20 minutes. It also minimises the visual and dramatic storytelling, making the music, played with tremendous lift and pace by the English Concert under Clemens Schuldt, the singers, and the audience, work hard.

Hannah Clark’s set is sparse and cryptic. In the original libretto the action takes place in various locales: a town square, a temple of Venus, royal apartments, Mitridate’s camp, a hanging garden, a prison tower. Here, we’re essentially in a wooden box, the back wall of which – later plastered with Mitridate’s battle-map – creeps imperceptibly forward during the performance, alluding both to the advancing, unstoppable Roman army and to the increasingly claustrophobic family dynamics. The strands of Mitridate’s life are heading towards explosion and implosion, respectively, the positioning of a huge, opulent designer sofa centre-stage in what is presumably the King’s military headquarters, perhaps suggesting a collision of the military and the domestic.

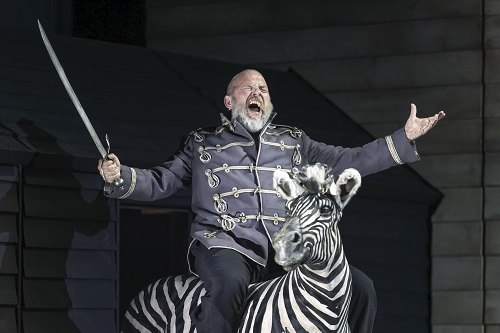

Scattered around the sofa there is a globe, a marble bust, a plumed helmet, a rifle cabinet (binoculars perched atop, ladder leaning alongside giving access to a battered lookout window), some toy soldiers … oh yes, and a life-size zebra. It’s as if Albery is challenging the audience, “Well, work this one out then …”. Perhaps there is something of deep psychological import going on here? But, to paraphrase Henry James, the costumes won’t tell. There’s plenty of black mourning, but the attire straddles eras. Iestyn Davies stands out against the sombre palette, sporting gorgeous silk pyjamas of glossy imperial purple hue, alluding to Farnace’s treachery, and then a smart magenta suit. Soraya Mafi’s Ismene also adds a splash of colour, dressed in an ugly pink frock and doc martens, and forced to endure a frightful blond bouffant hairdo. No wonder Farnace’s not interested in romance.

The empty set seems vast, and the cast often look stranded, but they use their skill and experience to deepen the characterisation through the music and gesture, and create credible relationships. The young Mozart evidently set out to show that anything Handel could do, he could do, if not better, then equally well. Inevitably, while there are some gems, not every arias is a masterpiece, but they consistently demand extreme virtuosity and all of the singers have the style absolutely under their skin.

Robert Murray’s Mitridate has fire in his belly, and the tenor launches at the demanding tessitura and register-jumps fearlessly, his upper register ringing brilliantly, and with impressive musical and emotive impact. The dishevelled, war-worn King arrives dragging a large, battered trunk (which contains his silver sword and gilded breastplate), and charges about the stage, fuelled by rage and vengeance. It’s perhaps not very regal, but his fury and unpredictability confirm his emotional instability, which only deepens as he learns of his sons’ betrayals. He stabs his sword into the military map, spearing Rome, the city he deludedly imagines he can invade and conquer. The insanity of this stratagem is evident when Mitradate leaps onto the afore-mentioned zebra (raising a few unintended chuckles). His gruesome final return from the battlefield gives new meaning to the word ‘blood-bath’.

Iestyn Davies relishes Farnace’s cruelty and ambition. He lolls petulantly on the sofa during the overture, playing with a toy helicopter while swigging whisky. When the spurned Ismene threatens to go to Mitridate, Farnace warns her that she could regret her revenge (‘Va, l’error mia palesa’), with chilling indifference. If anyone can make marathon-length arias of incredibly demanding floridity communicate with dramatic nuance, then Davies can, and from the heated opening aria, ‘Al destin, che la minaccia’, his glorious countertenor effortlessly filled the house and sailed through the coloratura. One might be tempted to say of Farnace’s final aria of repentance, ‘Già degli’occhi il velo è tolto’, in which he vows to lead a life of honour, ‘classic Davies’ – but, that would not do just to the beauty of line and tone, and risk forgetting the intelligence, skill and musicianship that inform such mesmerising singing. The villain’s volte face, a requisite of the genre, may not be entirely credible, but Davies could make a telephone directory expressive and dramatically persuasive.

As Sifare, soprano Louise Kemény injects much passion into her pure, soaring lines. When Asparia, despite her love, tells Sifare to leave her and uphold his honourable duty, ‘Lungi da te’ powerfully conveys the self-sacrificing lover’s acceptance and suffering, the vocal line wonderfully complemented by Ursula Paludan Monberg’s superb horn obbligato. On the surface, Elizabeth Watts is a dignified Aspasia, but she releases her conflicted inner feelings with terrific vocal richness and precision, not least in the contemplative ‘Pallid’ombre’, in which she prepares to commit suicide by drinking a cup of poison.

Soraya Mafi sparkles through Ismene’s stratospheric outbursts, the clarity dazzling, but she is no less expressive in the recitatives in which she communicates her pain and frustration in the face of Farnace’s suffering. As Arbate, Mitridate’s counsellor, tenor John Graham-Hall looks on with horror at the unfolding traumas and sings his sole aria stylishly. The Roman tribune, Marzio, also has just a single aria, sung with agility and warmth here by tenor Joshua Owen Mills.

Marzio wears a grey, WW2 Russian army great coat. At the close, he is stabbed when Farnace sees the error of his ways and repents. Perhaps there’s more to this gesture of resolution than initially meets the eye? Under Mitridate’s energetic leadership, Pontus expanded to absorb several of its small neighbours. Mitridate himself died in 63 BCE, in Panticapaeum, which is now in the Ukraine.

But, if Albery’s ‘meaning’ remains ambiguous, then this production confirms both the young Mozart’s genius and the cast’s stunning Mozartean authority and artistry.

There are further performances of Mitridate on 9, 11, 23, 27 June and 2 July.

Claire Seymour

Mitridate – Robert Murray, Aspasia – Elizabeth Watts, Sifare – Louise Kemény, Farnace – Iestyn Davies, Ismene – Soraya Mafi, Arbate – John Graham-Hall, Marzio – Joshua Owen Mills; Director – Tim Albery, Conductor – Clemens Schuldt, Designer – Hannah Clark, Lighting Designer – Malcolm Rippeth, The English Concert.

Garsington Opera at Wormsley; Saturday 3rd June 2023.