Composer-pianist Nikolai Medtner (1880-1951) has sometimes been labelled, like his compatriot and friend Sergei Rachmaninov, as being ‘born too late’. The late-Romantic idiom in which they both wrote, well into the twentieth century, was seen as behind the curve of the compositional developments of the era. Medtner was a triple émigré, fleeing Russia after the Revolution, living first in Germany (his parents had German ancestry), before moving to France in 1924. In 1927, he was invited to perform in Russia, where he was warmly received, but the denial of permission to return to his homeland led him to emigrate once more, this time to England, where he remained until his death, working solely as a composer. This very fine SOMM disc, released in August this year and titled Medtner in England, does much to overturn some of the misconceptions about his music, and reveals Medtner as a musician whose compositional discipline and skill is allied with a stirring soulfulness that is deeply Russian.

Medtner published 106 songs during his lifetime but here we are presented with the posthumously assembled Eight Songs Op.61 (published 1954) which span from 1927 to 1951.[1] Recorded in their entirety for the first time, the songs, which set both German and Russian poems, are essentially Romantic in idiom, but they bring together features from the West and East. They are performed by the British-Russian baritone Theodore Platt and the London-domiciled Russian pianist Alexander Karpeyev. Platt couldn’t wish for a better musical partner. Alexander Karpeyev has not only been a major prize winner at a number of international piano competitions but was awarded a doctorate on the music of Medtner, and in 2010 he began organising Medtner festivals in the UK as well as the first English-speaking conference dedicated to Medtner, at the British Library in 2016.

These are challenging songs for singers. First, there’s the chromaticism of some of the vocal writing, as the voice moves out of alignment with the harmonic changes in the accompaniment. In some songs, Medtner seems to have conceived of the ‘meaning’ of the song as being encompassed in the piano accompaniment, and so the vocal melodies seem to emerge from the latter rather than forge their own direction. Theodore Platt has the requisite technique, expressive nuance, and importantly, boldness. And, not least, a lovely rich baritone which is even from top to bottom.

The first two songs are settings of texts by Joseph von Eichendorff (1788-1857). ‘Reiselied’ (Journeying Song) has a steady tread, but it is not the careworn trudge of Schubert’s wanderer; rather, the piano’s chorale-like introduction establishes a tone of optimism which is complemented by the inter-stanza episodes of vocalise – a sort of carefree wanderer’s whistle. Also, by the forthright declaration at the close, marked by Platt with a heightening of intensity and dynamic, that though the journey may at times be smooth, at others rough, “I know that I can never stray,/ my God, from this your world”. Platt’s ringing sustained note emits confidence, just as the firm rise at the start of the assertion, “the sky is now my roof”, reassures. And, despite the regularity of the rhythm and meter, there’s a freedom and looseness which is beautifully easeful.

‘Nachtgruß’ (Greeting) shares the religiosity of the preceding song but is more harmonically complex, and greater responsibility lies with the piano to articulate the sentiments of the song – which Karpeyev’s rich palette and flexible rhythmic flow evoke – in extended inter-verse commentaries. Platt, though, is ever alert to the way his darkened voice can heighten the details of the text, with key words – in the first stanza, for example, “quiet”, “sleep”, “everlasting light” and “peace” – expressively shaped within the mellifluous phrases. The closing vision of the “new king” who “tak[ing] the throne in the silent realm,/ ascends the eternal heights” grows in magisterial splendour.

Two Pushkin settings follow. In ‘What is my name to you?’, in confrontational fashion the poet-speaker laments the loss of his place in his beloved’s heart, only at the close to urge her to retain a memory of him so that “There is a heart in the world where I live on”. While the poet-speaker tries to remain composed, the piano, with its rich chromaticism, dense chords and pounding triplet repetitions, betrays his anguish and agitation. But, Platt does not neglect the nostalgic tenderness within the song, softening his baritone as he subtly reminds his lover of the affectionate memories that they share. His final urgings are forceful and compelling, but his eternal desire is conveyed in the closing line by Platt’s wonderfully controlled head voice, which lifts the song above anger towards transfiguring hope.

In ‘What is my name to you?’, the piano doesn’t help the singer much, but Platt is rock-steady, and the same is true of ‘If life deceives you’, a short, but delightful song which looks to the future as a balm for life’s cares. Again, the duo create a lovely mood of optimism: Platt’s diminuendo on a high sustained note at the end of the offering of solace, “Everything is fleeting, everything will pass”, is both skilfully executed and deeply touching. Medtner responds to the faith and certainty of Lermontov’s ‘Prayer’ with more settled harmonies and greater concordance between voice and piano. Though the idiom is very different, it has something of the feel of a Bach chorale. Again, Platt shows that he knows how to build through a song – loud, plunging octaves, “And then, believing and weeping”, give way to softness and succour, “And such lightness, lightness …”, the latter captured by the piano’s affecting rising appoggiatura at the final cadence.

The final three songs are settings of poems Fyodor Ivanovich Tutchev (1803- 1873) often referred to as one of three great Russian poets of the Romantic era, along with Pushkin and Lermontov. They were written towards the end of Medtner’s life, the latter completed only two months before his death. Karpeyev’s slinky acciaccaturas and woozy triplets capture the hazy languor of ‘Noon’, while Platt’s extended vocal phrases seem to hover harmonically ‘on’ the accompaniment, rather than sit within it, creating a wonderful effect of strangeness. Platt’s final wordless melisma is like a yawn of satisfying sensuousness, as Pan “Drowses in the cave of the nymphs”. A struggle between the worldly and the spiritual preoccupies the speaker in ‘Oh my foreboding soul’, and the duo powerfully evoke the man’s soul and growing agitation. In ‘Repose’ life is passing by, like a rushing river – evoked by Karpeyev’s cool, rippling triplet semiquavers – never to return. Here, Karpeyev’s textural clarity and Platt’s vocal expressiveness – some lovely quiet high notes – persuade a listener that this song, indeed all of the set, are the equal of Rachmaninov, if not better.

The Sonata-Idyll Op.56 (1937) was the last of Medtner’s 14 Sonatas for piano. It comprises two movements, a brief ‘Pastorale: Allegro cantabile’ and a more substantial and more elaborate Allegro moderato e cantabile. Medtner was at this time, Francis Potts – author of the detailed booklet article which covers Medtner’s life, compositional style and offers informed commentary on the works performed – tells us, ‘trying to pare down the difficulty of his piano writing’.

If this is so – and perhaps the intention was fuelled as much by his publisher’s wishes as by his own aesthetic concerns – then in the ‘Pastorale’, at least, he fulfilled his aims. Karpeyev conveys all of its innocent beauty, while allowing the intricacy of some of the rhythmic interplay and the tinge of an interrupted cadence or unexpected harmony to hint at shadows. The sparse three-part textures, which are brilliantly elucidated, the perpetual counterpoint and the chorale-like melody put one in mind of a Bach invention, but the ornamentation is unquestionably Romantic, and under Karpeyev’s flexible fingers, full of grace.

For all its elaborateness, metrical complexity, wealth of melodic material and textural variety, the Allegro moderato e cantabile retains its sunny disposition – confirmed by the closing tremolos which glisten with a quiet joy which fades into an arpeggio tenderly reaching for infinity. Karpeyev makes the whole movement sparkle with joie de vivre and a playfulness which belies the virtuosic demands. The torrents surge with controlled abandon, melodies sing, dotted rhythms skip, chordal punctuations push down deep into the keys and their release sets free more imaginative gambolling and galloping. Karpeyev responds brilliantly to the kaleidoscopic mood swings but also perceives how they form an absolutely coherent whole.

The disc opens with Medtner’s Violin Sonata No.3, ‘Epica’, in which Karpeyev is joined by the London-domiciled Russian violinist Natalia Lomeiko. The sonata was begun in Paris in 1935 but not completed until 1938, following Nikolai’s final emigration to London. It is dedicated to his brother Emil, who had died in 1936. The Sonata certainly is ‘epic’ in scale, at almost 45 mins; in her memoirs, his wife explained that Nikolai had intended to orchestrate the work, which suggests that he viewed it as ‘symphonic’ in scope and ambition.

Lomeiko and Karpeyev grasp its rhapsodic magnitude with gleeful passion and daring. The piano chords which open the slow introduction (Andante meditamente) to the first movement Allegro toll gravely but warmly, and the violin’s sumptuous double-stopped siciliano has a folky flavour, with its modal tints and rhythmic character. One is reminded that when in England Medtner had converted from his parents’ German Lutheranism to Russian Orthodoxy: perhaps the nostalgia expressed through this Russian spirit was felt not just for his brother but for his homeland too?

Lomeiko’s tone is gloriously rich, by turns gritty, fierce, sweet, always expressive. A lovely cantabile leads in the Allegro, the subito flick of the switch a rude awakening – they’re off! The strepitoso semiquavers trip up neither player, always light and fleet, despite the density of the counterpoint. That Medtner’s complex dismantlings and reassemblings are so lucid and seem so inevitable is due to his compositional skill – one is always aware of the ‘whole theme’ even as it is broken down and tossed ceaselessly between the players; to the clarity of the performers’ articulation and phrasing, and the persuasive way that they transition between different episodes, sometimes with the slightest hiatus which serves as a springboard for what is to follow; and also to the SOMM engineers who have produced such a well-balanced, clean and bright sound. The spirit of the Russian dance is never absent, though the perky second theme has a neoclassical feel, too. The rhythmic impetus is perpetual; one feels almost breathless just listening!

The Scherzo, which borrows a Russian folk melody, is infectiously joyful, its virtuosity effortlessly mastered here. The duo brilliantly integrate the moments of cantando grace – and a brief, tender ‘Trio’ – within the prevailing spiky scurrying. The rhythmic ingenuity even incorporates a few slaps-of-the-thigh à la Cossack. I imagine they were grinning as they brushed the impishly quiet final chord!

The piano bells of the opening movement return at the start of the Andante con moto, reinstating a contemplative air. In the winding violin theme – played by Lomeiko with gutsy intensity, a seamless legato and expressive nuance – one hears again the echo of Russian church music, although I was also minded of Mussorgsky, particularly when the theme is supported by the piano’s weighty chords. As the players swap the theme between them at times, the piano’s eloquence accompanied by firm pizzicatos, double stops and subtle countermelodies, one becomes aware just how much this Sonata presents a partnership of equals. The Finale (Allegro eroico) which follows segue, is not quite as long as the first movement, but its still a big beast. So much is here: virtuosic whirlwinds, sharply etched; graceful song; spirited dancing; an across-the-beat march; a Russian Easter chant; an improvisatory duo-cadenza. The elements are ‘tangled’ together with astonishing coherence. It’s like being in an ocean with wave after wave bringing something new, but all part of the same sea.

As a sometime-violinist, I feel embarrassed that I did not know this wonderful Sonata, and fortunate to encounter it for the first time in a performance of such deep feeling given by such splendid advocates for Medtner’s music – a performance which conveys every ounce of their absolute commitment to the Sonata. My interest is more than just piqued: clearly if one does not know the music of Nicolai Medtner, then one doesn’t really understand and appreciate Russian musical art of the late 19th century and early 20th century.

Though some have found Medtner’s music conservative, this disc proves that the opposite is true: he was an innovator who built creatively upon the past. His close friend Rachmaninov had predicted a great future for Medtner’s music, and he was surely right. He might have had to wait a while, but this terrific disc will now play its part in bringing his genius to the fore, and help confirm Glazunov’s assertion that Medtner was ‘the firm defender of the sacred laws of eternal art’.

Claire Seymour

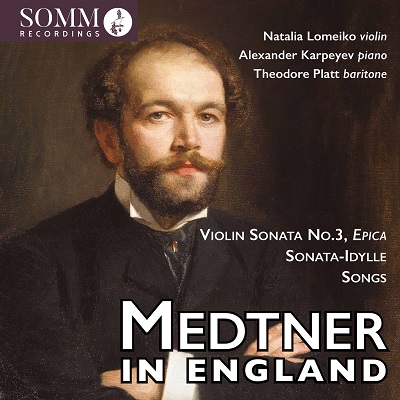

Medtner: Theodore Platt (baritone), Natalia Lomeiko (violin), Alexander Karpeyev (piano)

Violin Sonata No.3 in E minor, ‘Epica’, Op.57; Sonata-Idylle in G major Op.56, Eight Songs Op.61

SOMMCD 0674 [74:18]

ABOVE: Centre Stage Artist Management

[1] The Medtner Society website suggests that ‘Noon’ (No.6) was originally published as part of Medtner’s Op.59 No.1 collection. Subsequently he used this opus for the Two Elegies, and the 1959 Collected Edition inserted this song into Op.61, causing a change in numbering of the last three songs. According to Barrie Martyn’s biography, Nos.3 and 6 were composed in the 1930s (premiered 1936), Nos.1 and 2 completed in 1945, and Nos.5 and 8 completed in 1951.