Continuing this year’s theme of the relationship between the musical, poetic and visual arts, this Oxford International Song Festival lunchtime recital purported to reflect the topics which ‘fixated the artists of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood – the recreation of an idealised Middle Ages, the celebration of Nature and of manual labour, the necessity of salvation, and above all, the telling of a story in a single image’ and to ‘[bring] to life the words of the Pre-Raphaelite poets’.

Mmm. So, we might have anticipated musical settings of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Algernon Charles Swinburne, George Meredith, William Morris, or of those who were influenced by these Pre-Raphaelites during the decadence movement of the 1890s, such as Ernest Dowson, Lionel Johnson, Michael Field or even Oscar Wilde, Gerard Manley Hopkins and William Butler Yeats.

The programme, carefully curated by David Owen Norris, who introduced the three parts of the recital, did offer a setting of Christina Rossetti: ‘Somewhere of Other’ by Alice Millais (1862-1946), the daughter of John Everett Millais. But, the recital essentially took us into the Victorian parlour and music hall, and, in the final part, gave us a sprinkling of Sullivan in pre-G&S mode. There were settings of William Henry Bellamy (1800-66), lyricist of popular music and hymns, and his fellow balladist Thomas Haynes Bayly (1797-1839) – the latter had been deceased almost a decade when, in 1848, the band of Pre-Raphaelite brothers first met to oppose what they felt was the artificial and mannered approach to painting taught at the Royal Academy of Arts. We heard, too, settings by Parry and Elgar of texts by the cleric, novelist and humorist Richard Harris Barham (1788-1845, more commonly known under his pseudonym, Thomas Ingoldsby). And, the final part of the recital comprised four of Sullivan’s songs, setting texts by lyricists, clergymen and the poet-philanthropist Adelaide Anne Proctor (1825-64).

But, if this recital didn’t actually do what it said on the tin, it was no less delightful for it, and showcased the vocal artistry and dramatic wit of soprano Anna Dennis and bass-baritone Ashley Riches. Riches brought the Simon the Cellarer – who loves his supping his wine more than the prospect of taking a wife – vividly to life in John Liptrot Hatton’s setting of Bellamy. Rather than a general ‘northern’ tint, perhaps the baritone should have ventured a Scouse accent (the song was a favourite of the Victorian baritone Charles Santley, who – like Hatton himself – was from Liverpool), but he relished the words, which he delivered with robustness, and his baritone has the heft and variety of hue to make much of the slight. In February 1844, The Spectator commented, in a review of Bayly’s Songs and Ballads, that the success of this poet of the ‘parlour, kitchen and all’ lay in ‘his power of reflecting the popular sentiment in a popular form’ and dealing ‘rather with sentiment than with feeling – still less with passion’. ‘Oh no! We never mention her’, Bayly’s setting of his own text, perfectly encapsulated this judgement, and Riches tapped the engaging qualities of that sentiment with vocal and dramatic astuteness.

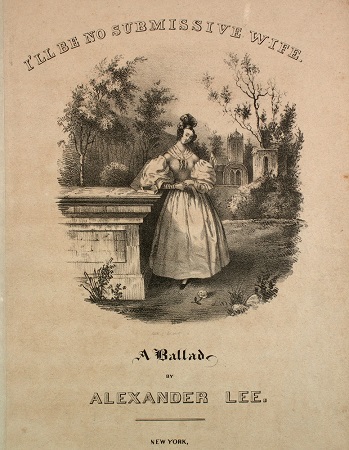

Henry Smart’s ‘The Lady of the Lea’ offers a more sophisticated engagement with a wry text (by Bellamy), and Anna Dennis modulated with superb control between serene contemplation and bright flashes of hyperbole, pushing the narrative forward in the central section then drawing the reins at the close to dwell sweetly and softly, with tongue-in-cheek earnestness, upon the image of the fair, young lady “Cold within the tomb … Sleeping peacefully”. Owen Norris was alert to the storytelling twists and turns of the piano accompaniment. Dennis enjoyed both the rhetoric and Rossinian flights of George Alexander Lee’s 1835 folk ballad, ‘I’ll be no submissive wife’, exploiting the sentimental style to suggest a deeper political purpose, which she underscored with steely explosiveness.

Despite the undertones of Lee’s ballad, feminism still had some roads to travel. In January 1885, the author of the ‘Recent Music’ column in The Saturday Review commented that ‘Miss Alice Millais has composed some very pretty music to Miss Christina Rossetti’s words beginning “Somewhere or Other”’. Still, one couldn’t disagree – nor with the view, confirmed by Dennis’s tender account, that ‘She possesses considerable artistic ability and a vein of genuine melody’. The soprano’s purity of tone and attention to the nuances and extension of the melodic line made Parry’s ‘There Sits a Bird on Yonder Tree’ beguiling, too.

Ashley Riches bravely launched into Elgar’s ‘As I Laye A-Thinkynge’, the quasi-orchestral expanse and melodramatic intensity of which made me, for some reason, think of the gilded hyperbole (some might say monstrosity) of the Albert Memorial. Elgar dedicated this poem to one Gertrude Walker, an upper-class lady who rejected both his ardour and his offering. Barham’s poem implies that the bird which “sat upon the spraye”, unmoved by the comings and goings of a “noble Knyghte” and “lovely Mayde”, is a figurative embodiment of a lost love who ascends to heaven. Perhaps the best word to describe Riches’ committed and vivid delivery of Elgar’s over-inflated musical rhetoric is magisterial.

The baritone was equally adroit at tapping the vein of Arthur Sullivan’s drawing-room ballads – songs that were, for the composer, a reliable source of income and popularity: a sort of society calling-card. Riches was amiable, urgent and earnest, as required, in ‘The First Departure’ (text by Rev. E. Munro) and ‘A Life that Lives for You’ (Lionel Lewin) – the latter was a delicious mix of sincerity and irony. ‘Guinevere!’ earned its exclamation mark. In the closing song, ‘The Lost Chord’, Dennis joined Riches in the form of an angelic echo, and the performers’ exploitation of Sullivan’s musical nuances and effects confirmed why this is one of the few of the composer’s ballads that do regularly appear in the recital room.

Owen Norris was an engaging presenter and made a good case for his programme. But, with their stanzaic repetitiveness, cloying sentimentalism and often formulaic musical language, these songs might simply have reminded us of the homeliness of the Victorian parlour. Riches and Dennis made them rather more than that.

Claire Seymour

Anna Dennis (soprano), Ashley Riches (bass-baritone), David Owen Norris (piano)

John Liptrot Hatton – ‘Simon the Cellarer’; Henry Smart – ‘The Lady of the Lea’; Thomas Haynes Bayly – ‘Oh no! We never mention her’; George Alexander Lee – ‘I’ll be no submissive wife’; Alice Millais – ‘Somewhere or Other’; Hubert Parry – ‘There sits a bird on yonder tree’; Edward Elgar – ‘As I laye-a-thynkynge’; Arthur Sullivan – ‘The First Departure’, ‘A Life that Lives for You’, ‘Guinevere!’, ‘The Lost Chord’

Holywell Music Room, Oxford; Friday 20th October 2023.