In a tribute essay to Kodály in the 1965 Aldeburgh Festival programme Benjamin Britten suggested, ‘There can be no composer of our century who has done more for the musical life of his country’. Kodály’s fellow Hungarian Bartók was acknowledged too, Britten commenting that both composers ‘together and separately, may be said to have re-created Hungary’s whole musical language’. One can readily detect a national style in this collection of choral works recently issued by Pentatone, each distinctive and individual if, in the case of Kodály, of uneven inspiration. Of Psalmus Hungaricus Bartók commented that it ‘could not have been written without Hungarian peasant music’.

Listening to Kodály’s Psalmus – a setting of a 16th-century paraphrase based on Psalm 55 by Mihály Kecskeméti and scored for orchestra, choir and tenor soloist – brought fond memories of a student performance I was involved in during the 1970s when it was sung in Edward Dent’s English translation. It is acclaimed as one of the truly great choral works of the 20th century, and while there’s no shortage of recordings, actual performances today are relatively rare. The Guardian’s Alfred Hickling once observed, ‘Kodály remains a minority taste in this country, lightly dismissed as a kind of low-fat alternative to Bartók’. A little unfair perhaps considering the emotional punch and drama of Psalmus Hungaricus in which the soloist assumes the role of the betrayed King David, with a supplicant chorus echoing his anguish and indignation. It was Kodály’s first major choral work, and its text, freighted with historic associations for all Hungarians, would have especially resonated with the composer’s feelings about the Hungarian government in the years immediately following the end of the Great War. The work was premiered in 1923 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the union of the cities of Buda, Pest and Óbuda.

According to the Kodály authority David Vinden, the Psalmus is a work ‘that sings itself’. Here, the Transylvania State Philharmonic Orchestra and Transylvania State Philharmonic Choir do the work proud. Under the direction of Lawrence Foster (American-born with Rumanian ancestry), the chorus respond fervently to the raging of the persecuted, bitterness giving way to the affirmation of God’s divine retribution. King David’s grievances are articulated mainly by the tenor Marius Vlad, but here his impassioned utterances sound a little too clenched for comfort, and only in the latter stages of the work does a more yielding tone emerge. While this performance may not achieve the gravitas or emotional intensity of Kodály’s own recording (Hungaroton, 1957), Lawrence Foster’s ear for balance is sure and his tempi well-judged.

Without any doubt, the Psalmus is a more convincing work than the Budavári Te Deum (1936). Despite an obvious festive spirit (the Te Deum celebrates the 250th anniversary of the recapture of Buda castle from the Turks), the work is somewhat unwieldy. This account feels longer than its 18 or so minutes, largely owing to some plodding tempos and some effortful singing which lends the fugues a suet pudding quality. The dense scoring doesn’t help, nor Foster’s insistence on pursuing the molto marcato markings to the letter. Too much risoluto becomes wearying and fails to take into consideration the demands made on the chorus, especially a high soprano part. Soloists acquit themselves well, with the soprano Luiza Fatyol bringing wonderful poise in her closing phrases.

Like the Te Deum, Bartók’s Cantata Profana (1930) is another rarity in the concert hall, although moderately well represented on disc. Based on traditional Transylvanian ballads (and sung here in Romanian), it narrates the tale of a hunter’s nine sons who are magically transformed into stags before their integration into the natural world. The work remains an under-appreciated part of his oeuvre, not helped by its taxing vocal parts, including much contrapuntal choral writing and some uncompromisingly high lines for tenor and baritone soloists. Its 1934 premiere in London, given by the Wireless Chorus and BBC Symphony Orchestra, was dismissed by The Times’ critic who mused, ‘it hardly seemed to be satisfactory choral music’. Balance difficulties evident in that performance disappear here, although there is at times some degree of strain from all voices. This account just misses the pagan element a performance demands, tempi just a little too safe in the hunt scene and, arguably, fractionally too fast in the portentous opening paragraph. Bogdan Baciu and Ioan Hotea, as father and son respectively, are impassioned in their solo contributions, manfully facing their extreme pitches. The chorus are assured and bring considerable energy to their role. That said, I would not want to be without the Solti recording with the Budapest Festival Orchestra (Decca, 1998), its excitement unsurpassed.

Taking the disc to just over the hour are Bartók’s Transylvanian Dances, orchestral versions of his Sonatina for Piano from 1915 and given characterful performances. Overall, these accounts are a worthwhile introduction to the composers’ choral works and make attractive couplings that enjoy full texts and translations with excellent sound.

David Truslove

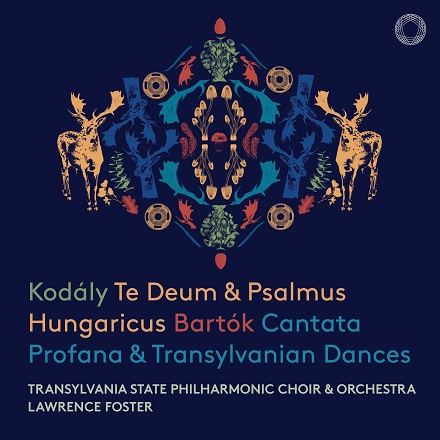

Kodály – Budavári Te Deum, Psalmus Hungaricus Op 13; Bartók – Transylvanian Dances Sz. 96, Cantata Profana Sz.94

Luiza Fatyol (soprano), Roxana Constantinescu (mezzo), Marius Vlad & Ioan Hotea (tenors), Bogdan Baciu (baritone), Junior VIP children’s choir, Transylvania State Philharmonic Orchestra and Philharmonic Choir, Lawrence Foster (conductor)

Pentatone PTC 5187 071 [64:14]