Kings Place’s annual celebration of a particular ‘theme’ has entered its sixteenth year, and in 2024 it is the turn of Scotland to be ‘unwrapped’. The year-long series will explore Scottish music and spoken word culture, highlighting both the traditional and the contemporary, and the diversity and distinctiveness of Scottish ‘voices’.

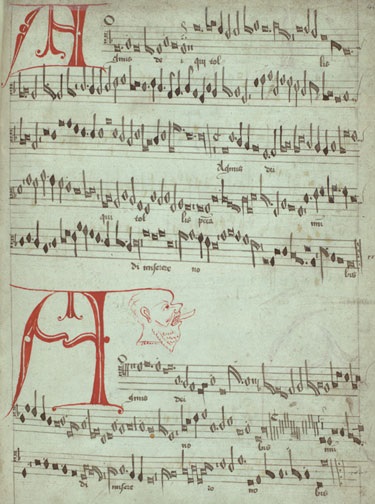

During the first half of the sixteenth century, Robert Carver (1485-1570) was one of the most prominent of those musical voices. He was mainly associated with the court of James IV, where he was a canon of the Chapel Royal at Stirling and for which he probably composed most of his works, and with the Augustinian Abbey at Scone near Perth. His five masses and two motets are preserved in a single manuscript which was known as Scone Antiphonary, although – being neither an antiphonary nor likely used at Scone – it has now been re-named as the Carver Choirbook. It contains, alongside Carver’s works, sacred music by Guillaume Dufay and by the English composers William Cornyshe, Robert Fayrfax, Walter Lambe and John Nesbet, perhaps attesting to their influence on Carver.

Harry Christophers and The Sixteen have long been esteemed advocates of the music of Carver and his Scottish (and English) contemporaries, and in this concert at Kings Place they offered a celebration of the Carver Choirbook, which drew upon and supplemented the programme presented on their 2002 disc, An Eternal Harmony.

Carver’s music documents the transitional period from a national style characterised by elaborate polyphony to the gradual influence of the imitative idiom which had developed in continental Europe. But, in this recital we heard examples of Carver’s employment of the former, first in the form of the Credo from his ten-voice Missa Dum sacrum mysterium (c.1513), a festal mass which resembles the music contained in the Eton Choirbook (copied c.1490-1502). Following the solemnity of the mass’s antiphon, sung with precision by the men of the ensemble, with all voices joining to spread warmth through the closing “Alleluia”, the Credo developed from lean opening textures – the intonation and balance took a little while to settle – to full passages in which varied combinations of voices blossomed in florid late-Gothic counterpoint.

The diversity of colours and combinations, wiriness alternating with warmth, duple- and triple-time interchanging, was invigorating. The melismatic style did mean that the text was sometimes difficult to discern (and it didn’t help that we had been plunged into gloom in Hall One, making deciphering the ‘Texts and Translations’ pamphlet all but impossible – something which was rectified in the second half), but one could not but admire the way the singers rose to the considerable demands, as the individual vocal parts roved widely, even as the harmonies sometimes seemed quite static. Christophers held the, at times rather eccentric, parts together into a coherent whole, driving forward from the richness of the low basses towards the satisfying culminating “Amen”.

From William Cornysh (1465-1523) there was more complexity and expanse, in the long lines and intricate rhythms of the Salve regine which is recorded in the Choirbook. (One should note that there are two composers of this name, father and son, and some scholars have argued that the Latin motets, including Salve regina,which are included in the Eton Choirbook might plausibly be attributed to the elder (d. 1502).) The forces were slightly reduced here, but the juxtaposition of the energetic polyphony in the lower voices and the shining clarity of the sopranos above created great dynamism, and, closing one’s eyes, there seemed to be myriad voices engaged in the rhythmic to-ing and fro-ing. Again, though the unceasing elaborations can sometimes cause these works to ‘flag’, Christophers articulated the punctuation points vigorously and the final resolution, “O dulcis Maria, salve!” shone.

The five-voice motet, Eternae laudis lilium (Lily ever to be praised), by Robert Fayrfax (1464-1521) was composed in 1502 in honour of Queen Elizabeth, the wife of Henry VII, who visited the Abbey at St Alban’s where Fayrfax had for four years been informator chori. Fayrfax’s writing is less elaborate than Cornysh’s or Carver’s, but this performance had a lovely flowing momentum as Christophers let the lines unfold in relaxed fashion. Again, the contrasts of timbre were exploited: the six stanzas are set for different vocal combinations. There was welcome gentleness, and gentility, here, though the words could have been more sharply defined.

For all the impressive scholarship and musicianship to be admired, this recital did prompt some questions. I have reflected before on the performance of historical devotional music in modern secular contexts. It’s difficult to judge the ‘tone’, I think. Here, The Sixteen looked very dapper, as if they might be about to set off for an Edwardian country house party: men in tails and white cummerbunds, women in deep-toned, glossy evening dresses. As always, the ensemble’s presentation and stage demeanour were immaculate, those shifting arrangements of personal so deftly choreographed and executed. But, there was at times something slightly surreal about hearing this music, and these words, presented in this context. I began asking myself whether there were other ways in which I might like to experience live performance of this music? I was, somewhat oddly, put in mind of singing with an a cappella ensemble in a remote, privately owned church at Dode in Kent, back in the 1990s, when we wore monks’ habits (very smelly and itchy) and the church was candlelit. Heaven knows what the fire brigade would have made of the ‘health and safety’ arrangements, had they known … but, it was certainly ‘atmospheric’.

That is something of a digression, but not an entirely irrelevant one, I think. In any case, while there may be no extant secular music by Carver (whose output was probably wholly sacred), the programme did venture into domestic domains, and into the seventeenth century, with three works, all à 6, by Robert Ramsey (1590-1644). Ramsey travelled south to become organist and master of the choristers at Trinity College, Cambridge. In monte Oliveti (On the mount of Olives) offered some Italianate imitation, tidily articulated, while the melancholy of O vos omnes was conveyed in the overlapping, falling phrases and expressively shaped suspensions. There was some lovely madrigalianisms here. How are the might fallen unfolded silkily, at times veiled, the tenors pushed high but remaining sweet, elsewhere the rhythms robust.

Often vocal programmes contrast this early repertoire with more modern voices. And, it was the inclusion of Sir James Macmillan’s O Bone Jesu (2002) – commissioned by The Sixteen and inspired by Carver’s 19-part motet of the same name – which gave this concert its ‘edge’. Like Carver, Macmillan’s Scottish and Catholic identity (I use the word as if in scare quotes) is communicated through his music. And, he has drawn on Carver elsewhere, in his Symphony No.4 (2015) which references the Roman Catholic Mass, Gregorian chant and quotations from Carver’s Missa Dum sacrum mysterium. In O Bone Jesu (O kind Jesus) the blending of Macmillan’s distinctive ‘voice’ and Carver’s musical idioms is inspiring. The Sixteen exploited every expressive nuance of the varied harmonies which inject vitality into the repetitions of the two-note “Jesu” motif which are the scaffolding for the work. Again, textures juxtaposed solo voices with rich groupings, becoming ever more intense and dense, the voices sometimes seeming to swirl and slide. Pungent dissonances sank into driving pedal points. Christophers sculpted the musical trajectory with skill and insight, the final “dulcis Jesu” forging a new direction, pushing upwards, the high dissonance refusing to resolve.

Carver’s massive motet concluded the programme. Christophers somehow made the intricate, melismatic traceries forged by the nineteen voices truly lucid, and there was a tremendous sense of flexibility and forward momentum. His singers had both the stamina and sensibility required.

Claire Seymour

Scotland Unwrapped: Carver Choir Book

The Sixteen, Harry Christophers (conductor)

Dum sacrum mysterium (plainchant); Carver – Credo from Missa Dum sacrum mysterium; Macmillan – O Bone Jesu; Cornysh – Salve regina; Fayrfax – Eternae laudis lilium; Ramsey – In monte Oliveti, O vos omnes, How are the mighty fallen; Carver – O Bone Jesu.

Kings Place, London; Friday 26th January 2024.