Nearly upended by a proposed strike from ENO musicians, which was averted for the opening night, the revival of this production of Poul Ruders’ The Handmaid’s Tale, first unveiled in 2022, sees the return of several significant cast members. Little has changed in Annilese Miskimmon’s production, rebooted here by James Hurley, and the work remains just as darkly prescient, perhaps even more so, as it did when the opera was premiered in Copenhagen in 2000.

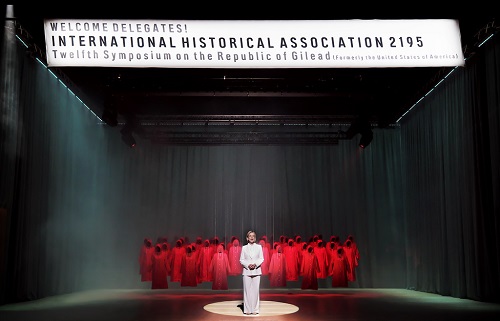

Brutal totalitarianism and private tragedy form the core of this chilling tale that has more than a few parallels today with extremist and misogynistic regimes. Framed by an academic conference in the year 2195 we encounter Professor Pieixoto (a superbly measured Juliet Stevenson) leading a study of the former Republic of Gilead established by Christian fundamentalists following an ecological disaster that caused tumbling birth-rates. In its Taliban-like regime women are denied education, property and rights, and those of suitable age are indoctrinated to become breeders for childless households. Once a month these Handmaids perform their productive function lying between husband and wife, an act recalling the handmaid in Genesis who fulfils this role for the barren Rachel.

A birthing table, an insemination desk and a prayer machine are just three of the disquieting accessories making their appearance on the Coliseum stage. Then there’s the Wall (more of a memorial than a public hanging place), its sinister presence behind an imprisoning curtain a warning for those who transgress in the repressive and futuristic Gilead of Margaret Atwood’s dystopian novel of 1985. The librettist Paul Bentley remains faithful to its 21st-century setting and shapes the work into two acts with a prologue.

At the work’s centre is American mezzo-soprano Kate Lindsey as Offred, whose husband and daughter (seen in videoed flash backs) have been snatched from her prior to her confinement at the Red Centre as a handmaiden. She inhabits this role with wonderful conviction, consistently claiming our attention (poised like a statue when seeing a photograph of her missing girl) and singing with clarity and heart-easing tenderness with Eleanor Denniss’ spirited Ofglen, and no more so than in her poignant second-act duet with her younger persona. But there’s defiance too, and an emotional reawakening initiated by her trysts with the amenable chauffeur Nick admirably sung by Zwakele Tshabalala.

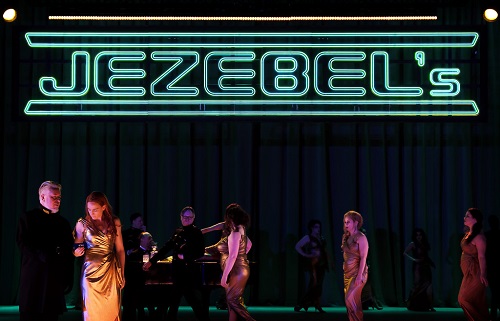

There’s an authoritative performance from Rachel Nicholls as the all-powerful Aunt Lydia who coldly declares to the Handmaids that ‘it is easier to think of your children as dead’. Stratospheric and angular vocal lines are taken in her stride, with her coloratura counterbalanced by the resonant contralto of Avery Amereau’s stony then conspiratorial Serena Joy – the barren wife of James Cresswell’s vocally cavernous Commander. Amongst other roles, Alan Oke and John Finden give persuasive cameos as the lecherous doctor and an ardent Luke, and Nadine Benjamin makes for a rebellious if, at times, over-egged Moira. A chorus of Handmaids intermittently glide across the stage like a flotilla of Dutch sails. Some relief from the gloom is found briefly in Jezebel’s, a glitzy brothel, but otherwise little is left to the imagination or to lift the spirits in Annemarie Woods’ uncluttered sets and Paule Constable’s sterile lighting, revived by Marc Rosette.

The grotesque hanging scene is a terrifying reminder of a state-sanctioned execution, its emotional intensity heightened by a Bach chorale embedded into Ruders’ eclectic and highly communicative score. Accessible, at least, in Ruders’ capacity to cherry pick numerous transatlantic references including echoes of Ives, Bernard Hermann, Berg and Penderecki, as well as periodic snatches of ‘Amazing Grace’. It all makes an intriguing kaleidoscope of material but, while these allusions catch the ear, it’s a shame the vocal writing for many of the characters, excepting Offred, is so unforgiving, so awkward and charmless for the singers. Hymn-like contours for the chorus provides some relief as well as the ever-shifting sonorities from the ENO orchestra, the whole magnificently performed and efficiently directed by Joana Carneiro.

David Truslove

Ruders: The Handmaid’s Tale

Offred – Kate Lindsey, Aunt Lydia – Rachel Nicholls, Serena Joy – Avery Amereau, The Commander – James Cresswell, Ofglen – Eleanor Dennis, New Ofglen – Annabella-Vesela Ellis, Luke – John Finden, Offred’s mother – Susan Bickley, Moira – Nadine Benjamin, Janine/Ofwarren – Rhian Lois, Nick – Zwakele Tshabalala, Doctor – Alan Okie, Rita – Madeleine Shaw, Professor Pieixoto – Juliet Stevenson; Annilese Miskimmon – Director, James Hurley – Revival director, Annemarie Woods – Designer, Paule Constable – Lighting designer, Marc Rosette – Revival lighting designer, Akhila Krishnan – Video designer, Yvonne Gilbert – Sound designer, Imogen Knight – Movement director, Anjali Mehra – Revival movement director, Chorus and Orchestra of English National Opera, Joana Carneiro.

The Coliseum, London; Thursday 1st February 2024.

All images (c) ENO/Zoe Martin