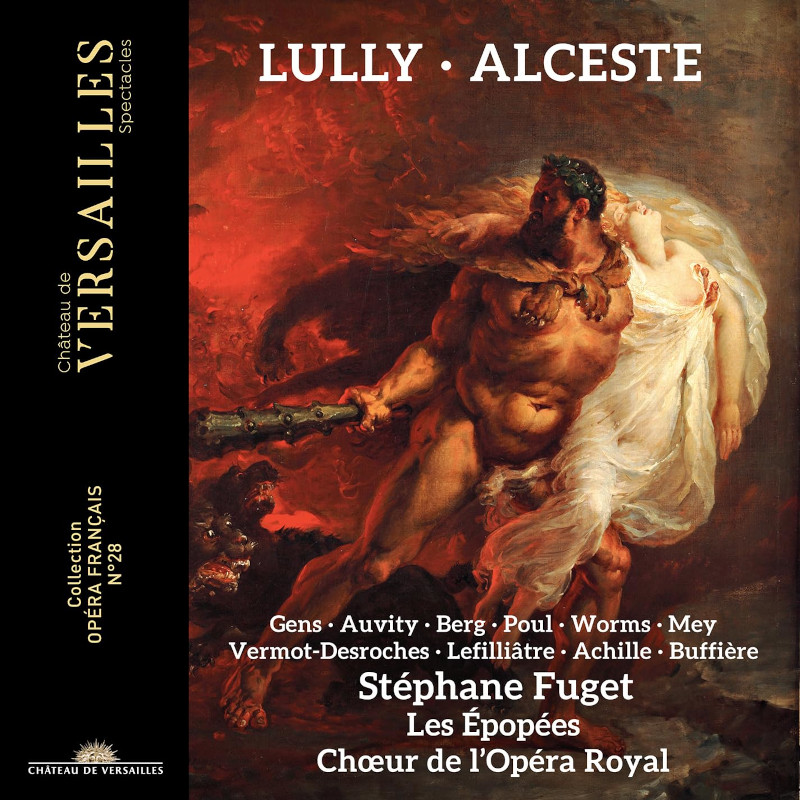

Lully’s “tragédie lyrique en prologue et cinq actes” Alceste is set to a libretto by Philippe Quinault, after Euripides (Alcestis). The first performance took place at the Theâtre du Palais-Royal on January 19, 1674; Alceste was Lully’s second tragédie en musique (Cadmus et Hermione was the first, again to a libretto by Quinault but this time after Ovid, first performed 1673).

This is an extended work (three hours, minus 27 seconds, of music) so does indeed have the space to encompass a wide range of characters and emotions. The timing implies this is as complete as it gets: Malgoire took 130 minutes in his famous but now rather outdated recording live from the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées in January 1992. The supporting cast there included the present Alceste, Véronique Gens, in a raft of minor roles, Proserpine the most significant, but also the Nymphes de la Marne and de la Tuilleries and the Femme affligée; “NA“ was complimentary about her in his Gramophone review, saying her ‘vocal technique and feeling for shapely melodic gesture are a constant pleasure”. Malgoire also recorded it in 1974 for CBS, with the much-loved Felicity Palmer in the title role. The live 1992 recording does embrace its live provenance, warts and all, and the recording is somewhat insubstantial. Still others might know Jordi Savall’s recording of the orchestral Suite from Alceste on his Alia Vox disc L’Orchestra du Roi Soleil – as raucous and as celebratory as Lully performance gets. But the big competition comes from arguably today’s greatest interpreter of Lully, Christophe Rousset on the Aparté label.If once thing is clear, we are living in a Golden Age of Lully opéra performance.

Alceste is one of the earliest of Lully’s operas (Thésée followed the next year, the first that Louis XIV fully controlled in the sense of reading the libretto and making modifications, allowing for extra propaganda to his own glory). The plot is moved forward by much recitative accompanied by continuo; dances and divertissements also play a part, as do chouses (in later Lully operas, the orchestra takes far more of a foregrounded role, particularly in Armide of 1686). We sit in Lully’s first operatic period therefore; one might posit a second period that is more overtly heroic (lots of machinery, people floating in from above, that sort of thing), and a third period, featuring more human drama, again with foregrounded orchestra.

It is important to note that while that trajectory might imply a forward movement, Fuget convinces us (as does Rousset on his recording) that it is not less interesting to have continuo ’in charge,’ as it were. Theatricality is all there, as is a sense of dramaturgy. As with Monteverdi, one has to be in the text and drama to allow for flexibility, and Fuget’s excellent recordings of Monteverdi on the Château de Versailles label seem to stand him in good stead. Fuget follows period practice of improvised continuo, his group including the bass viol.

Unfortunately, there was no full score of Alceste. But there are several handwritten orchestral scores and several copies of edited scores, plus editions published by the King’s publisher, Ballard. The orchestra used in this recording includes woodwind and bass. Fuget follows known period performance practice of including varied percussion, including tambourine in the pastoral dances and elsewhere.

The large canvas of Alceste means Lully can work with a number of character types, including the comedic. It was this diverse mix that created some controversy at the time (contrasting with the more straight-laced tragedies of Corneille, for example; incidentally, Chrisophe Rousset once told me, there in relation to Thésée, that he considers Quinault the best of Lully’s librettists). So, for example, Alceste, Alcide, Admète and Lycomède are all serious characters; Céphise, Lychas and Straton, King Phérès and Charon offer light-hearted contrast.

Stéphane Fuget and his group Les Épopées are no stranger to the Château de Versailles label: those forays into Monteverdi are magnificent. Previously, they have concentrated on Lully’s sacred music. Founded in 2008 by Fuget, Les Épopées brings a vivacity to all their recordings, and that is certainly the case here. The emotive power of the Overture is palpable in Fuget’s performance. Dotted rhythms carry weight, the faster passages are well sprung, ornaments ever tight. If anything, Fuget is even more raw than Rousset.

The Prologue is set on the banks of the Seine, in the Tuilleries garden. The Nymph of the Seine appears (Cécille Achille) lamenting the absence of her hero. This is real lament, too: Achille is superb in conveying the Affekt as well as individual moments: suspensions make maximal impact; fine as Lucia Martin Carón is for Rousset, Achille seems to penetrate closer to the heart of the character’s pain. Claire Lefilliâtre is La Gloire herself. While the two voices are differentiated, I would have welcomed a little more differentiation in emotion and Affekt: when La Gloire asks the Nymph, ’Pourquoi tant de murmure?’ (deliciously translated as ’Why whine so much?), Lefilliâtre is too soft-toned in her demand; in contrast, Judith Van Wanroij for Rousset leaves us in no doubt that this is a very different character. When Fuget’s two singers sing together (‘Qu’il est doux’), the resultant combination does work extraordinarily well, though; the segue to the entrance of the chorus is superbly managed, and the chorus of the Royal Opera at Versailles proves itself one of the finest choirs out there.

Camille Poul is the Nymph of the Tuilleries, her air introduced by the addition of woodwind to the sound picture: ‘L’art d’accord de la Nature’ (Art in accord with Nature) reveals a voice that is mild in timbre until mezzo-forte and above, when there is a not inappropriate slight hardening. Juliette Mey is a gentle Nymph de la Marne (try ’L’onde de presse’). Talking of the woodwind contributions, it is nice of the oboes to turn up when they are mentioned in the text (”Le Chant des Oiseaux s’unisse / Avec le doux son des Hautbois’) . The orchestra is superb at elevating the mood at the very end of the Prologue (preparatory to ‘Revenez, plaisires exiles;’ Come back, exiled pleasures).

The Prologue itself takes in a surprisingly wide remit of emotions. Act I takes us to a port in Thessaly, where preparations for the wedding of Alceste and Admète are underway. Alcide, however, is jealous, telling Lycas he opts to not attend, to spare himself emotional pain. The Lycas, Léo Vermot-Desroches (who takes a total of four roles during the course of the opera) sings against Nahan Berg’s Alcide. Vermot-Desroches is the most incredibly sweet-toned tenor; Berg is a nicely resonant bass-baritone. Berg’s Alcide does sound definably bereft. Again, when they sing together (‘L’Amour a bien des maux, mais le plus grand de tous,’; Love certainly has many sorrows) it is clear much thought has gone into casting. Against that is the excellent no-nonsense delivery of Geoffroy Buffière as Straton.

Camille Poul also takes on Céphise, and her beautifully light (but not insubstantial) voice against the low bass of Straton is effective indeed in the fourth scene of the first act. It is a wonderful moment in Lully’s score when Céphise & Stratton sing “You must always change/love. For the sweetest love Is the new/faithful one,” and their lines chase each other, only to agree at the cadence (on the word ’toujours’). Bass –baritone Guilhem Worms is a fine Lycomède, the King of Skyros, his contribution full of lyricism. But maybe it is the sheer beauty of Aeolus’s (Éole’s) ‘Le Ciel protège les Héros’ that impresses the most: Buffiere is superb.

It is a very close thing between Fuget and Rousset in this first act and Prologue; the clinching factor is Rousset’s total grasp of the score which gives every element a sense of ’place’. Fuget reacts beautifully to every nuance, beyond doubt. Without Rousset, Fuget would be first choice, but how sweet now the options.

Act I introduces a raft of plot intricacies and crossed loves: Céphise with Lychas and Straton; Alceste with Lycomède and Admète. Towards the end of the act, Lycomède and Straton lead Céphise and Alceste onto Lycomède’s ship under false pretenses; they are kidnapped, the ship sailing to Skyros.

Act II is set on Skyros itself. Céphise is prisoner, as is Alceste. The first panel of the act focuses on the impossibility of love in forced circumstances. Such meditations in recitative seem to feed Fuget’s imagination: the way the group changes the mood at ’L’injuste enlèvement d’Alceste’ is stunning. Enemy troops led by Admète and Alcide approach. King Lycomède refuses surrender and prepares for a siege. Alcide and Admète take the city; however, Alceste discovers Admète, mortally wounded by Lycomède. Lycomède is saved by Apollo, as long as someone dies in his place …

Musically, the act is dominated by Véronique Gens’ Alceste. Gens is simply beyond criticism. Those who have heard her ’La mort, la mort barbare’ on the ’imaginary opera’ released by Alpha, Passion, will have had an inkling of what she can do, but what joy to hear her in the complete role. Lully saves his most astonishing writing for the titular heroine, and how Gens and Fuget relish every moment. Worms is strong again, although in this act there is a slight tendency to scoop up to notes.

Vermot-Desroches drips with character in this act as Phérès. But Lully’s writing at the “death” of Admète is utterly astonishing: Fuget allows us to experience this heart-breaking moment full force. The Admète is the wonderful Cyril Auvity, who has impressed multiple times previously (as Amor in Lully’s Psyché at Versailles, for example); his duet with Gens’ Alceste is a moment when time stops still. But this is of course myth, so death might well not really be death. Apollo (Vermot-Desroches, here decidedly nasal and very French-sounding) offers a way out via that life swap. Someone has to go …

It is the central third act where Lully takes us to really dark places, and the opening of the first scene leaves us in no doubt of this. The third act is the hub of the opera, where Fuget takes us on an extraordinary journey: the cries of the chorus (”Hélas!”) hang in the air miraculously. The subsequent lifting of mood is perfectly judged. But Lully’s musical coup is the funeral march – nasal as they come here, and Rothko-dark. The vocal contributions mirror this: Claire Lefilliâtre as “Une Femme alligée” is simply superb in her mourning. Fuget gets real depth, too, notably in Admète’s “Sans Alceste,” Auvity’s plangent tenor ideal; Berg is at his finest in this act, too, as Alcide. I remain intrigued, however, about what sounds almost like a morris-dancing entr’acte (the last track on the second disc). If anything, Rousset’s third act is even more notable, a processional, an exploration of death like few others.

The fourth act takes us to the river Acheron, where shades await Charon, who arrives in his boat. He is filtering those who can pay and those who cannot. Guilhem Worms’s strong bass-baritone furnishes the requisite energy for his opening air, “Il faut passer tôt ou tard” (You have to cross sooner or later”); but really the admiration is for Lully. What a walking bass the composer provides, and how resolute the instrumentalists of Les Épopées. The ghosts (“Les Ombres”) respond in an appropriately disembodied (and unaccompanied) fashion. Berg makes for an insistent Alcide (he jumps into Charon’s boat, and commands the ferryman to take him to Pluto).

And indeed they do go to Pluto’s palace via a scene change that is so impeccably of the grandeur of Louis XIV. Buffière has real presence as Pluto, with Juliete Mey a clear yet tender Proserpine. This is an act of sudden changes, not just of scene but of stance, for Pluto moves from adversary to advocate of Alcide in his search for Alceste. A word here for the sheer excellence of the chorus: “Tout Mortel doit ici paraître” (All mortals must appear here): the Chœur de l’Opéra Royal hits the restrained mood perfectly, just as they nail the more incisive rhythms in “Chacun vien ici-ba” (Each one of us comes down here). It is also one of the most inventive acts when it comes to continuo contribution; Pluto’s lines can be caught up in a veritable web of sound.

The final act brings resolution for the minor/comic characters. Lychas frees Straton; Céphise has to choose but refuses, saying she will not marry; in an operatic moment that requires some suspension of belief (as if other elements of the plot don’t!) both suitors accept their lot and all get stuck into the party for Alcide’s triumph.

It is the grandeur of the orchestral lead-in to Alcide’s “Pour une si belle victoire” (For such a magnificent victory) that seems so perfectly of Versailles. It leads not to a grand chorus, though, but to dialogue between Alcide and Alceste; the happy ending is yet some way, and the farewells of Alceste and Admète are moving indeed: Gens and Auvity is one powerful combination. This is no tidying up of ends in the fifth act; it is a full-on emotional roller-coaster and Fuget and his players and singers live every moment. The denial of happiness due to the honoring of duty by Alceste and Admète cuts to the quick. It is Vermot-Desorches in his role-incarnation as Apollo who ties it all together, celebrating Alcide’s triumph and the joy of Admète and Alceste.

Both Fuget and Rousset’s recordings underline the importance and genius of Lully’s early opéra. Fuget is involving throughout every note, painting the tale viscerally; Rousset’s perhaps slightly deeper view is more for the ages.

The Château de Versailles Spéctacles recording is demonstration standard. There is a full libretto, synopsis and essays, with English and German translations in the 215-page booklet. A lavish presentation for a lavish production. Recommended on so many levels: but it is Lully who is the winner here. Fuget proves that Lully’s Alceste deserves our full attention, that it is a masterpiece.

Colin Clarke

Alceste

Composer: Jean-Baptiste Lully; Libretto: Philippe Quinault

Alceste – Véronique Gens; Alcide – Nathan Berg; Admète – Cyril Auvity; Lycomède, Charon, Un homme désolé – Guilhem Worms; La Nymphe des uilleries, Céphise – Camille Poul; Lychas, Phérès, Alecon, Apollon – Léo Vermot-Desroches; Cléante, Sraon, Pluton, Éole – Geoffroy Buffière; La Gloire, Une Femme affligée – Claire Lefilliâtre; La Nymphe de la Marne, Proserpone, Diane, Thétis – Juliete Mey; La Nymphe de ls Seine, Une Nymphe, Une Ombre – Cécile Achille

Conductor – Stéphane Fuget; Chœur de l’Opéra Royal (Lucille de Trémiolles, director); Les Épopées

Recorded in the Salle des Croisades at the Château de Versailles, January 26-29, 2024

Château de Versailles Spéctacles CVS 149 (three discs 179″33)

The digital and physical release date is 14th of March 2025 in the UK and 11th of April 2025 in N. America. It will be available from Presto Music, ArkivMusic and other vendors.

Top image: Véronique Gens. Photo © Sandrine Expilly.