My apologies for not having posted this review online earlier. The recording was made back in 2017, and I reviewed it for American Record Guide. I should have thought to offer it to Opera Today at the time. (I have permission from that distinguished magazine to repost my reviews elsewhere.) But Les Troyens is such an important work, and John Nelson’s recording is so richly worthy of it, that I am delighted to draw attention to it here, even belatedly.

Les Troyens is—scholars, critics, and performers agree—the supreme achievement of Berlioz’s mature years. He wrote the libretto himself, basing it on Virgil’s Aeneid, which he knew intimately in the original Latin. Most opera lovers have little sense of this masterful work.

For one thing, it has only recently begun to secure an established place in the repertory of the world’s opera houses—and, with its eighteen sung roles, many of them extremely demanding, only in the best-funded of them.

For another, what is most wonderful about the work—its vast scope and variety—does not lend itself to excerpts in the concert hall or on aria collections. The one number that is most often recorded on its own, the “Trojan March” (currently available recordings include ones led by Weingartner, Beecham, Zinman, and others), is, almost by definition, more conventional than most of the score. Listening to it on its own, one would have no sense that it returns again and again in the opera, reorchestrated, with voices against it, even reharmonized (including as a minor-mode dirge in the brass instruments, after which it lends its motives to a meditation for full orchestra).

Indeed, the conventional—to use that word again—mind-state of the Trojans and their leader Aeneas is one of the many painful and interwoven dramatic messages in this work. The Greeks’ determination to conquer Troy and subjugate its people (the basic story of Acts 1-2) strongly suggests Berlioz’s understanding of the nature of power politics and military might. Just as his description of a near-utopian civilization in Carthage (Acts 3-5) reflects his lifelong frustration with the France of his day—not least its, in his view, frequent hostility toward artistic inventiveness—and his search for alternatives elsewhere, notably in Germany, where his works encountered much greater appreciation. (Inge van Rij offers a rich discussion of Berlioz’s many-sided fascination with different places and peoples, real and imaginary, in her recent book The Other Worlds of Berlioz: Travels with the Orchestra.)

There are other hurdles as well, for performers and for listeners. The writing for the voices is rarely showy—unlike in, say, parts of Gounod’s Faust—yet the work is not at all Wagnerian, either. The orchestral score, highly complex and variegated, requires immense rehearsal time to allow it to be performed with the necessary transparency, with attention to the frequent layering of disparate types of music atop one another, and with highly precise rhythmic coordination. There are also moments when the instruments become very exposed. I had forgotten, until listening to the new recording, just how lengthy and contrast-filled the clarinet solo is in the Act 1 pantomime for Hector’s widow Andromache and their son Astyanax: the clarinet seems to be emitting a quasi-improvised aria representing Andromache’s unspoken grief and discouragement. (I use the standard English names for these characters from Greek mythology. The cast list above gives the French names.)

Despite the many challenges, Les Troyens is finally getting performed and recorded with more regularity than ever before. It reached Chicago’s Lyric Opera for the first time in 2016, and, three years earlier, a Met telecast allowed millions to see Francesca Zambello’s new production (with Deborah Voigt, Bryan Hymel, and Susan Graham). The work keeps getting heard in concert performances, sometimes with Acts 1-2 (the ones set in Troy and featuring Cassandra) on one concert and Acts 3-5 (the ones set in Carthage, where we meet Dido) on another. Berlioz was forced to bisect the work in this way, much against his will, as a condition for getting Acts 3-5 performed. Acts 1-2 were never heard during his lifetime.

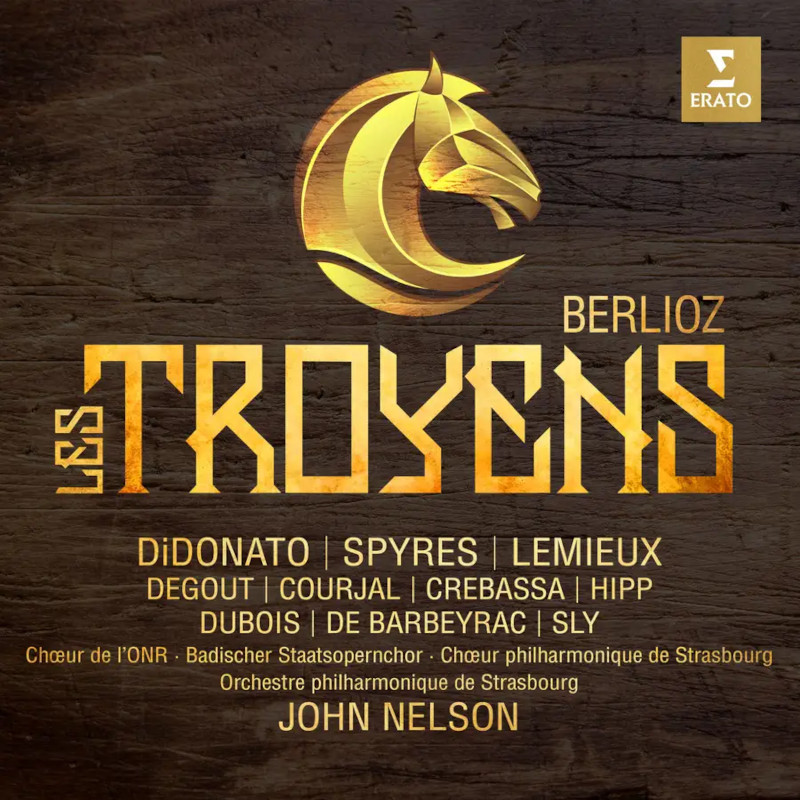

The present recording, made from one or more concert performances plus patch sessions in April 2017, is led by John Nelson, former music director of the Indianapolis Symphony. Nelson, something of a Berlioz specialist, has conducted the work at the Met. He has also recorded Berlioz’s other two operas, the Te Deum, and—twice, with different singers—Les nuits d’été.

Over and over, while listening, I found myself swept along, feeling a tidal surge, for example in the stirring, near-hallucinatory finale to Act 2. It helps that the tempo is sometimes (though not always) faster than on other recordings. A real treat: all the singers sound as if they know what they are singing about. It surely helps that most of them (I note three exceptions below) are native French-speakers. The chorus, in particular, comes across as a character in the drama more than I ever noticed before

The two main female singers are, as Cassandra, Marie-Nicole Lemieux, whose Rossini-aria CD I praised highly in American Record Guide (September/October 2017), and, as Dido, Joyce DiDonato, a world-renowned Rossini specialist—from Kansas—who has been branching out in widely different roles. The main male role, Aeneas, is taken by Michael Spyres—“born and raised in the Ozarks,” as his site informs us. I have previously admired Spyres’s singing in Mayr’s Medea in Corinto and, even more (because there he didn’t force his upper register), in Hérold’s Le Pré aux clercs. Each of these three supremely gifted singers conveys the shifting emotions that her or his character undergoes, while never exceeding the limits of secure and controlled vocal production.

Spyres is perhaps the most secure Aeneas to have recorded the role. Set against the passionate and visionary Jon Vickers, on Colin Davis’s history-making first complete recording, he occasionally sounds almost too composed and “normal.” (The high notes pose no challenge for him.) But, if this is a fault, it is one that will make the performance wear well in repeated hearings. Lemieux’s voice seems exactly right for Cassandra: she can soar high as needed but has the necessary lower notes as well. All of which helps her indicate numerous shadings of emotion.

The only thing that might become tiresome from these three main performers, I suspect, is DiDonato’s basic tone when she is singing solo and loudly: in recent years, she has increasingly given long solo passages an edgy sound: a near-constant throb or flutter. The resulting intensity would be more effective if saved for special moments. DiDonato’s throb is not a wobble (which I hate as much as anybody), but it is definitely not the rounded warmth that one encounters in performances of this role by, say, Régine Crespin, Tatiana Troyanos, or Susan Graham, or, for that matter, in what one hears, on this very recording, from Marianne Crebassa (as Aeneas’s 15-year-old son Ascanius).

Interestingly, the edgy throb is largely absent when DiDonato sings softly, as in the Act 4 Quintet and Septet. Indeed, she can sing super-softly, to eloquent effect. So her reading of the role achieves variety largely by contrasting loud and soft singing, rather than within longish full-voiced passages. One big exception: the throb is near-constant in Dido’s concluding scene, even when she sings very softly. Perhaps this was an artistic decision: to show Dido’s now-consuming sense of distress. In earlier scenes, for special purposes, DiDonato occasionally sings a few notes with no vibrato at all. Vibrato is thus something this remarkable singer can turn on and off at will. (I should also mention that the throb bothered me much less on the DVD of excerpts, to be discussed below, because DiDonato is such a compelling actress.)

Another aspect of dynamics: I noticed many places where DiDonato ends a phrase by pulling back the volume so much that, in a large hall, the final note or two would possibly not carry across an orchestra. But perhaps that is one advantage of recorded opera: it allows a singer to experiment with interpretive effects that might have little impact in front of 4,000 listeners. (The Salle Erasme in Strasbourg, where these performances took place, seats a mere 1,876.) A parallel can be found in opera films and videos, in which close-ups and cross-cutting allow singers to use subtle and swiftly changing gestures and facial expressions.

I should mention that DiDonato articulates the numerous melismatic moments in the Septet more precisely than I have ever heard them done. No surprise, given how masterful she is at coloratura (e.g., in Handel and Rossini). That factor, combined with Nelson’s forward-flowing tempo, makes the Septet sound more poised and contented than ever, more Mozartean, but also, perhaps inevitably, less darkly pensive than in some other performances.

The other medium-size and small roles are mostly well staffed. I enjoyed, more than ever in the past, Cassandra’s lengthy interactions with Chorebus (Stéphane Degout, assured except for a touch of, yes, wobble) and Dido’s with her sister Anna (Hanna Hipp, a Polish mezzo whose rich voice contrasts helpfully with DiDonato’s bright one). The role of Iopas is performed by my current favorite French lyric tenor, Cyrille Dubois, though here his very lowest notes lack a secure stream of breath. (I praised him unstintingly in my reviews of Félicien David’s Le désert and six songs by the same composer.) The Hylas does not hit his pitches clearly and steadily, and his low notes do not fully “speak.” The two sentinels are superb: what a difference native French-speakers can make in semi-comic roles! The Narbal has a cavernous quality to his tone that bespeaks authority. But I often had trouble making out what pitches he was semi-barking. (Again, I noticed the odd vocal production less in the DVD excerpts, described below.)

This new recording has been hailed in the press (Gramophone, New York Times) as the best-ever recording of the work. For so complex a work, there will probably never be a simple “best.” I would say, more cautiously, that the new set is one of the three most effective ways to get to know the work on CD (see below). A further plus: the booklet is first-rate, giving the remarkable David Cairns translation of the libretto and a first-rate essay by Christian Wasselin. The latter is generally well translated, but with a few over-literal equivalents.

Some other CD recordings have their own merits or even selective magnificences. The main contenders are two conducted by Colin Davis (studio recording, 1969; and concert performance, 2000) and one by Charles Dutoit (studio, 1993). For the characteristics of these three (and other recordings, generally weaker, dimly recorded, or incomplete), see the Berlioz Overview (May/June 2007) in American Record Guide. Briefly, the ARG critics favored Davis I above Dutoit and Davis II: for the conducting, orchestral playing, and Jon Vickers’s indelible Aeneas. In the Act 4 love duet (“Nuit d’ivresse”), Davis takes a very leisurely tempo, but he sustains it well and varies it in dramatically apt ways as it goes along. (His solid if sometimes tremulous Dido is Josephine Veasey.)

To all of these commercial CDs, I would add a Met CD set from 2003, which was, at one point, available directly from the Met Opera Shop at the amazing price of $21. (Amazon.com lists it as no longer available, with used copies going for $249!) It features commanding performances by Deborah Voigt, Ben Heppner, and an extremely artful Lorraine Hunt Lieberson as Cassandra, Aeneas, and Dido, and is conducted with weight, brilliance, and wide-ranging emotional contrasts by James Levine. The orchestral contribution to this magnificent opera has never been more fully realized than in Levine’s splendid, spirited CD set. (The Anna and Narbal are somewhat wobbly.)

The new one conducted by Nelson comes close to Davis I (1969) and the Met 2003 CD set in many passages and outdoes them in others. And, unlike in those recordings, there is no weak link in Nelson’s cast (unless you are allergic to DiDonato’s throb). I suspect that Nelson, Davis I, and the Met CD set (if you can find a copy) are—taken together—now the best ways to get a full sense, on CD, of what Les Troyens has to offer. Studio excerpts by Régine Crespin and Janet Baker will always remain well worth hunting down (and of course are easily available on the current streaming services, such as Spotify).

But that is just on CD! Some DVDs demand to be mentioned, given how unfamiliar this opera still is. The American Record Guide’s Overview praises the Levine Met DVD from 1983 (I remember being wowed by Jessye Norman’s Cassandra and Tatiana Troyanos’s Dido when the production was first telecast; Plácido Domingo was never perfect for Aeneas and soon retired the role) and also had good words for the John Eliot Gardiner DVD from 2003 (notable for Anna Caterina Antonacci’s Cassandra and Susan Graham’s Dido; Gregory Kunde was a bit light-voiced for Aeneas and the voice, at that moment in his career, not ideally steady). Gardiner has the added plus of letting us hear—as nobody else has on CD or DVD—the original, allegorical finale to the opera (though he removes some sections of it).

In the Love Duet to which I referred earlier, Gardiner’s orchestra—playing period instruments—comes across more as a collection of separate colors than I have ever heard before. I found the numerous short entries from the woodwinds distracting. Many of the same details in the winds can be heard in the Davis I CD set, with modern instruments and at a slower tempo; they are just made more subtly. (The state-of-the-art sound quality provided by the Philips engineers—yes way back in 1969—enables one to pay attention to all kinds of things.) Some critics objected to the updated costumes and at times puzzling sets in Gardiner’s DVD. The production on the Met DVD is more straightforward.

There is also a DVD from a 2012 performance at Covent Garden, conducted by Anthony Pappano, of which I have seen some excerpts. The cast is extremely international, but some of the singers are major ones: Antonacci as Cassandra, Hymel as Aeneas, and Eva-Maria Westbroek as Dido. (There may also have been a CD pressing of this, perhaps now out of print. The Covent Garden production was reviewed here at Opera Today ; a concert performance with the same conductor and leading singers was reviewed here.) And I have seen mention of another DVD from La Scala, conducted by Pappano, with Antonacci, Kunde, and Daniela Barcellona. (Its audio portion is at YouTube.) Neither Pappano DVD was reviewed here. Some of the individual portrayals in them may be well worth getting to know.

Speaking of DVDs, the new recording comes with a bonus DVD, giving 85 minutes of excerpts from the concert performance. The singers’ acting, even while standing in place and often looking at their scores on music stands, helped me then “see” my way into more details in the set’s four CDs. Alas, the DVD has no subtitled translations.

However you get to know it, Les Troyens is one of the major operatic masterpieces of the nineteenth century—on a par with, say, Aida or Die Walküre. I am grateful to Nelson’s new recording for reminding me of this, moment by wondrous moment.

Dozens of Berlioz lovers (named in the booklet) donated to the non-profit foundation known as Ascanio’s Purse. That foundation sponsored the recording, as it earlier did Nelson’s recording of Benvenuto Cellini. Interestingly, the foundation holds the copyright on the four CDs here (though not on the DVD) and assigned it to the record company. Presumably this will enable the foundation to re-release the recording if Erato lets it go out of print. The whole process offers a good model, I suspect, for getting a composer’s works recorded and kept continuously available.

Ralph P. Locke

Les Troyens

Composed by Hector Berlioz

Libretto by the composer

Marie-Nicole Lemieux (Cassandre), Joyce DiDonato (Didon), Hanna Hipp (Anna), Marianne Crebassa (Ascagne), Michael Spyres (Enée), Cyrille Dubois (Iopas), Stéphane Degout (Chorèbe), Philippe Sly (Panthée), Nicolas Courjal (Narbal), Stanislas de Barbeyrac (Hylas, Hélénus), Bertrand Grunenwald (Priam), Jean Teitgen (shade of Hector, Mercury), Richard Rittelmann (soldier, Greek chieftain), Agnieszka Slawinska (Hécube), Jérôme Varnier and Frédéric Caton (sentinels 1 and 2).

Strasbourg Philharmonic Orchestra and Chorus, Rhine Opera and Baden State Opera (Karlsruhe) Choruses, cond. John Nelson.

Erato LC 02822 [235 minutes, plus 85-minute video].

Click here to purchase and sample tracks.

Top image: Aeneas And His Family Departing From Troy by Peter Paul Rubens (1602-03) courtesy of Wikiart