Artistic Director David Agler is presenting his fifteenth, and final, Festival Programme – one which offers Wexford audiences their first Baroque opera since the Festival’s 1985 production of Handel’s Ariodante. Artistic Director Designate Rosetta Cucchi first came to Wexford as a member of the music staff in 1995, has been Agler’s Associate Director since 2005, and has directed many WFO productions including Francesco Cilèa’s L’Arlesiana (in 2012) Mariotte’s Salomé (in 2014) and Alfano’s Risurrezione (in 2017).

During an animated press conference, Cucchi introduced her programme for WFO 2020 and set out her plans for the future, which include ‘themed’ programming, four late-night Cabaret des Artistes performances, WFO 2.0 – a series of free pop-up, multi-disciplinary performances featuring music, drama, singing and dance which will be performed in non-traditional settings in various locations around Wexford town – and, perhaps most significantly, the establishment of the Wexford Factory, a new intensive academy which will offer professional and financial support to fifteen young Irish or Irish-based singers in the early stages of their careers. Cucchi will be the eighth Artistic Director of the Festival, and on 1st November she will present this year’s Tom Walsh Lecture alongside Elaine Padmore, who was the Festival’s fifth Artistic Director, from 1982-94.

And so, what of this year’s operatic offerings? Well, the first production that I saw during this Festival was borrowed from La Fenice in Venice, where it was presented earlier this year, with several members of the cast reprising their roles here. Antonio Vivaldi’s three-act melodramma eroico pastorale, Dorilla in Tempe, was first performed on 9th November 1726 in Venice’s Teatro San Angelo and in several ways exemplifies the mores and practices of Baroque opera. Antonio Maria Lucchini’s libretto mixes pastoral and heroic elements in presenting its ‘X loves Y, who desires Z etc.’ plot.

Manuela Custer (Dorilla), VÈronique ValdËs (Nomio) and Marco Bussi (Admeto). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Manuela Custer (Dorilla), VÈronique ValdËs (Nomio) and Marco Bussi (Admeto). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Thus, Apollo, who is disguised as the shepherd Nomio, has fallen in love with Dorilla, daughter of Admeto, King of Thessaly. She, however, is in love with the shepherd Elmiro. When the valley of Tempe is threatened by a sea-serpent, Admeto is compelled to offer Dorilla as a human sacrifice, but she is rescued by Nomio who claims her hand in marriage as his reward. Elmiro and Dorilla flee; Filindo sets out to find them, hoping that his deeds will win the heart of Dorilla’s sister, Eudamia, who also loves Elmiro. In fact, it is Nomio who captures the fugitives and resolves the conflicts, first saving Dorilla from waters into which she throws herself when Elmiro is condemned to death, and then, as Apollo, restoring harmony through divine intervention.

Structured conventionally as a series of da capo arias with celebratory choral scenes concluding each act, the extant score is in fact something of a patchwork. Dorilla in Tempe was revived several times during Vivaldi’s lifetime, with various alterations, and the score that survives seems to be that performed during the Carnival season of 1734, when Vivaldi converted the work into a pasticcio, inserting music by his contemporaries (including Hasse and Giacomelli). At least ten arias are not from Vivaldi’s own pen, while the Sinfonia concludes with a version of the composer’s Primavera concerto which, fittingly, evolves into the opera’s opening chorus in praise of spring.

Director Fabio Ceresa and set designer Massimo Checchetto take their cue from this seasonal reference and present the drama against the backdrop of a year’s unfolding cycle. Visually, it’s a feast. We begin with the purity and innocence of springtime: a sparkling white double staircase rises in pristine glory, decked with fecund green and cerise branches, and topped with statues representative of handsome Hellenic heroism. When summer comes, nymphs and shepherds sunbathe languorously in a golden glow. By autumn the trees are at their full height, but their heavy copper boughs hang low in the soft rosy light. Finally comes the stark chill of winter, the icy white garden now bare and unforgiving.

Rosa Bove (Filindo). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Rosa Bove (Filindo). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

The well-defined colours of Simon Corder’s lighting design and Giuseppe Palella’s luxurious costumes, and the extravagance of whole design, remind us how important the visual dimension of Dorilla in Tempe would have been in 1726, when the audience enjoyed Antonio Mauro’s elaborate sets and danced choruses choreographed by Giovanni Galletto. Here, the feats of Vivaldi’s contemporary engineers are matched by the slithering menace of the Chinese-dragon sea-snake; the giant tree-trunks that surge upwards more swiftly and slickly than Jack’s beanstalk; the beautiful stag-masked dancers who recreate the balletic triumph of the hunt, to the accompaniment of the horns’ stirring flourishes.

JosË Maria Lo Monaco (Elmiro). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

JosË Maria Lo Monaco (Elmiro). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

The dramatic conception is less satisfying, though. Essentially, Ceresa presents an opera of three acts, the constituent parts of which don’t cohere into a convincing whole. In Act 1, Greek Classicism provides an opportunity for some Carry On capers and campery. Dorilla (Manuela Custer) is a May Queen, her ‘wedding-dress’ sprinkled with spring flowers. Admeto (Marco Bussi) is a spoiled, sulky, tantrum-prone tyrant, encumbered with an emerald train so long that he must gather it up like a babe-in-arms in order to assert his authority, and more interested in stuffing himself with sugary swiss roll sweet-treats than saving his subjects from the marauding Python (Pitone). Faces are often covered (why the surgeons’ masks for the chorus – is the valley of Tempe less than temperate?); legs and midriffs are frequently bare. As the gold lamÈ boots, silver hot-pants, John Lennon sunglasses and floral effusions piled up, I felt as if I’d been gorging on Admeto’s candied cup-cakes.

Marco Bussi (Ademto). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Marco Bussi (Ademto). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

While some gentle mockery of the gods might be apt and advantageous – offering subtle pastoral irony to soften the dramatic heroics – Ceresa’s histrionics run counter to the sincerity of Vivaldi’s music. Surely when Elmiro (an ardent JosË Maria Lo Monaco) defies Admeto and Eudamia, and insists on the integrity of his love for Dorilla, we should believe and admire him? So why are his avowals treated as a joke, mocked by a parade of exploding parasols?

Similarly, when Filindo (an impetuous and impassioned Rosa Bove) declares his intent to track down the errant lovers, why are his preparations – the cleaning of his rifle barrel – interrupted by a paper bird on the end of a pole which dangles, distracts and diverts from the sentiments of his aria? Time and again, arias are disrespected in this way: when Eudamia (whose haughty presumptuousness was well communicated by Laura Margaret Smith) issues her challenge to the smitten Filindo, she – or at least, her gown – is transformed into a sea cave, equipped with treacherous waves and struggling boats – into which Filindo is himself drawn (to drown in the service of love?).

Laura Margaret Smith (Eudamia) and Rosa Bove (Filindo). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Laura Margaret Smith (Eudamia) and Rosa Bove (Filindo). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Then, in Act 2, things quieten down (and lose momentum as the da capos accumulate), while in Act 3 they turn decidedly nasty. When Nomio returns with the fugitive lovers, Admeto orders that Elmiro be executed. Nomio’s subsequent aria has a grisly backdrop: a dancer is hung upside-down by his ankles and his ‘skin’ flayed, as the blood-red glare deepens. Presumably this is a reference to the slaying of Marsyas, who had the gall to challenge Apollo, played his flute abominably, and whose punishment was to be stripped of his skin (which was destined for a wine-sack) in a cave near Celaenae? Nomio/Apollo as vindictive victor?

VÈronique ValdËs (Nomio/Apollo). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

VÈronique ValdËs (Nomio/Apollo). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

All credit to VÈronique ValdËs for her vocal virtuosity which competed admirably with such visual diversions. While the cast were entirely comfortable with Vivaldi’s elaborate vocal demands, ValdËs was the most compelling among them, her tone full and dark – her delivery robust and agile. Ironically, this Nomio was convincingly ‘human’. Bass Marco Bussi was much more persuasive in magisterial mode in Act 3 than as the King of Camp at the opening. Manuela Custer’s Dorilla was a cool-headed maiden, singing with purity and intensity. Fortunately, we had an opportunity to enjoy the full range of Custer’s expressive arsenal – a strong chest voice, superb control of phrasing and dynamics, pliancy of line and beautiful vocal tone – in an imaginatively programmed recital of Italian song, which took us on a journey through her homeland, in St Iberius Church two days later.

Conductor Andrea Marchiol encouraged the Orchestra of Wexford Festival Opera to play with vigour and dramatic punch, and they obliged, but at times the orchestral fabric felt a little too heavy for voices already working hard to surmount Vivaldi’s virtuosic challenges.

If one may have doubts about the staging, then Ceresa’s production certainly convinces one of the merits of Vivaldi’s score – whatever the provenance of its constituent parts – which complements the range of dramatic moods explored, from melancholy to rage, despair to triumph. The final apotheosis of Apollo – a golden god whose magnanimity bathes the mortals in its glorious gleam – was a satisfying conclusion to what was a rather bombastic Baroque burlesque.

Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Photo credit: Clive Barda.

The following evening, there was more visual extravagance: in the form of the three-tier wedding cake that forms the centrepiece of Tiziano Santi’s designs for Rosetta Cucchi’s production of Rossini’s Adina, a confectionary explosion which is complemented by the coloristic extravagance of Claudia Pernigotti’s costumes. This was another ‘import’, first seen in Pesaro in 2018. Here, Adina was preceded by a new work by Andrew Synnott, La cucina – a work designed less as a companion to Rossina’s one-act farce, and more as an explanatory preface to Cucchi’s hyperactive production.

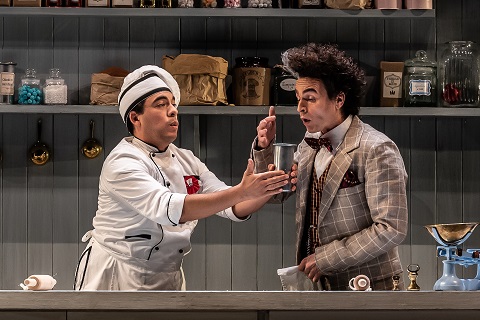

Emmanuel Franco (Camillo Aiuto cuoco) and Luca Nucera (Alberto). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Emmanuel Franco (Camillo Aiuto cuoco) and Luca Nucera (Alberto). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Cucchi, who wrote the Italian libretto for La cucina, explains that ‘La cucina serves a very specific purpose: it is a short prelude leading gently to the comic drama of Adina’ and that she and Synnott ‘worked hard to establish a very different mood from Adina’s’. Whereas Adina is a ‘dream’ – a ‘party of the mind’ – La cucina is ‘set in a very mundane world where disappointment, failure and setbacks are always around the corner’. Well, okay, but both are marked by Cucchi’s restless creativity which refuses to let score, text or action speak for itself.

Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Photo credit: Clive Barda.

La cucina is essentially the story of the cake: the one that must be dished up to satisfy Alberto – the famous chef, who has been left mute and traumatised by a Bake Off soggy-bottom disaster at La Scala – and the one that, in Adina, serves as a ground-floor Caliph’s bathroom, and a first-floor boudoir for Adina as she awaits her marriage to the Caliph, and a second-floor prison for Adina’s beloved Selimo. And, which is topped by live ‘Ken and Barbie’ avatars who add to the roster of ‘extras’ Cucchi deems necessary to tell Rossini’s tale.

M·ire Flavin (Bianca). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

M·ire Flavin (Bianca). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Synnott writes sympathetically for voices (as evidenced by his Short Work based on two tales from Joyce’s Dubliners, presented at the 2017 Festival), and his culinary caper is neatly devised and executed. Bianca (a superb Máire Flavin, who whizzes through the kitchen whirlwinds and relishes her more sombre reflections), assistant to Michelin-starred Alberto (Luca Nucera), is teaching a newcomer to the kitchen (Emmanuel Franco – whose lunchtime recital suggested, rightly, that while his baritone is a little wayward at times, he has a keen feeling for dramatic opportunity and an agile, responsive voice) the rites of professional perfectionism. Flour is flourished, dropped and mopped; deliveries don’t appear. The patience of Alberto’s put-upon staff runs out and they flounce off. Alberto has an epiphany: his ‘special ingredient’ is redundant and his power of speech restored. The kitchen personnel are eventually reconciled, and the cake is confected – just in time to take pride of place in the ensuing Adina. Whether Synnott’s opera will find a suitable occasion when it might be revived is another matter.

Sheldon Baxter, Manuel Amati, M·ire Flavin and Emmanuel Franco. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Sheldon Baxter, Manuel Amati, M·ire Flavin and Emmanuel Franco. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

In a programme article, Cucchi explains that while devising her production of Adina she was ‘deeply inspired by the whimsical worlds of Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland and Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel’. The semiseria libretto makes reference to only five characters, but Cucchi includes so many others – gardeners, cooks, marching bandsmen, ‘men in black’ wielding plastic rifles, two mini-Adina maids – that I half expected the White Rabbit to race through the harem or the Red Queen to strut in and order heads to be whipped off. Farce requires a certain simplicity and neatness, but here Cucchi offers superfluous personnel, ceaseless busyness and unnecessary complication.

Manuel Amati (AlÏ) and Daniele Antonangeli (La Caliph). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Manuel Amati (AlÏ) and Daniele Antonangeli (La Caliph). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Adina is enslaved by a Caliph who, astonished by her resemblance to his first love, Zora, urges her to marry him, while respecting her personal feelings (four decades after Mozart’s Seraglio, Rossini thus presents a more light-hearted version of contemporary orientalism). Adina, believing that her beloved Selimo is dead, reluctantly agrees to be his bride. But, of course, Selimo is very much alive, and trying to wangle his way into the harem. With the aid of the gardener, Mustaf‡, Selimo and Adina are reunited, but their plot to elope is discovered by the Caliph’s close friend, AlÏ. With Selimo under threat of death, a portrait concealed in a necklace reveals Adina to be Zora’s, and thus the Caliph’s, daughter. A happy ending thus ensues.

Rachel Kelly (Adina). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Rachel Kelly (Adina). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Irish mezzo-soprano Rachel Kelly was a fine Adina. Lisette Oropesa made her Pesaro debut in Cucchi’s 2018 production (Oropesa will sing in concert with the WFO Orchestra at next year’s Festival), and this was also the role in which Joyce DiDonato first appeared at Pesaro, in 2003. But, Kelly was, rightly, in no way daunted or overshadowed by these illustrious forbears, and her clear, crisp mezzo made a strong impression, even though the tessitura of the role is fairly low. Vibrato was used sparingly but expressively, emphasising Adina’s innocence. Kelly competed gamely with some dangling strawberries in Adina’s most familiar aria, the ‘Strawberry cavatina’, and with Cucchi’s ‘extras’ elsewhere.

Italian tenor Manuel Amati employed his firm and focused tenor effectively, as the eunuch, AlÏ, while Emmanuel Franco once again displayed a strong stage presence as Mustaf‡. Daniele Antonangeli was a magisterial Caliph, the Italian’s dark, handsome bass-baritone suggesting that Adina’s romantic choice was not as simple as it might seem. South African Levy Sekgapane’s deliciously seductive tenor stole the show, for this listener. As Selimo, his Italian diction may have been in need a bit of work, but Sekgapane rose gloriously to Rossini’s rapturous high-flying lines and his tenor delighted with its soft sweetness. Many in the O’Reilly Theatre evidently enjoyed Cucchi’s production very much, though I found it over-populated and rather out-dated in manner.

Levy Sekgapane (Selimo). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Levy Sekgapane (Selimo). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Rossini made another appearance during the Festival, at Clayton Whites Hotel, in the form of one of this year’s Short Works. L’inganno felice (The fortunate deception) was composed for the San MoisË Theatre in Venice in 1812 (along with Adina, La Cambiale di Matrimonio, Il Signor Bruschino and La Scala di Seta – it was a busy year for the 20-year-old Rossini). In his Vie de Rossini, Stendhal praised L’inganno felice as a herald of great things to come: ‘Here genius bursts forth from all quarters’. And, we were treated to an excellent staging by director Ella Marchment and designer Luca Dalbosco, whose economical set – a few wooden mine-shaft entrances, tables and stools – deftly conjured the locale and offered opportunities for intrigue.

Peter Brooks (Tarabotto) and Rebecca Hardwick (Isabella). Photo credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Peter Brooks (Tarabotto) and Rebecca Hardwick (Isabella). Photo credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Marchment demonstrated a sure sense of how to balance the opposing moods of the semiseria plot. Yes, there was an exuberant, erotic dream-escapade during the overture – which was played with a light, crisp touch by pianist/music director Giorgio D’Alonzo – but thereafter all was rooted in reality: a sooty, grimy and briny reality of the sort that communicated the experience of Isabella (Nisa), once betrothed to Duke Bertrando but deceived and betrayed by Ormondo – who hoped to win Isabella for himself – with the aid of his snivelling side-kick Batone. Having been cast adrift on a stormy sea, Isabella was rescued by the kindly Tarabotto, head of the local coal mines, from whom she has kept her identity secret … until, some years later, the Duke comes calling.

Thomas D Hopkinson (Batone) and Henry Grant Kerswell (Ormondo). Photo credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Thomas D Hopkinson (Batone) and Henry Grant Kerswell (Ormondo). Photo credit: Paula Malone Carty.

The cast demonstrated vocal and dramatic poise throughout the quick-moving action. Rebecca Hardwick was an assured Isabella, easing through Rossini’s coloratura, demonstrating a sure sense of phrasing, and convincingly balancing melancholy with determination. As Duke Bertrando, tenor Huw Ynyr was forthright of heart and voice. Thomas D Hopkinson, as Batone, coped admirably with the expansive range required and if he was occasionally defeated by Rossini’s fiendish fioritura then this was more than compensated for by his theatrical nous. Peter Brooks’ light baritone was perfect for Tarabotto, Isabella’s saviour, while Henry Grant Kerswell was an imposing Ormondo who, flung down a sealed-up mine at the close, satisfyingly got his comeuppance. Breezing along buoyantly, Marchment’s well-judged production told its touching tale of fidelity rewarded and virtue triumphant most engagingly.

Daydreams and down-to-earth reality were similarly entwined in the other two Short Works presented this year. The eponymous protagonist of Bizet’s Doctor Miracle has nothing to do with the murderous villain who, in The Tales of Hoffmann, persuades Antonia to sing, thereby causing her death. Offenbach is, however, indirectly responsible for Bizet’s second opera which the then 18-year-old Frenchmen wrote in 1857. A competition organised by Offenbach required entrants to compose an operetta to a libretto, Le Docteur Miracle, by LÈon Blum and Ludovic HalÈvy. There were 78 candidates, and first prize was shared by Bizet and Charles Lecocq, the winning entries subsequently being performed, eleven times each, in alternation, at Offenbach’s ThÈ‚tre des Bouffes-Parisiens in April 1857.

Lizzie Holmes (Laurette), Guy Elliott (Pasquin), Simon Mechli?ski (Mayor) and Kasia Balejko (VÈronique). Photo credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Lizzie Holmes (Laurette), Guy Elliott (Pasquin), Simon Mechli?ski (Mayor) and Kasia Balejko (VÈronique). Photo credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Blum and HalÈvy’s drama stretches credibility but does show how far the besotted will go in the name of true love. The Mayor’s daughter, Laurette, is in love with Captain Silvio, but her father disapproves and advertises for a servant whom he hopes will protect his daughter from amorous and military advances. Disguised as ‘Pasquin’, courtesy of eye patch and club, Silvio is appointed to the role. He cooks a disgusting omelette for lunch, is promptly sacked, and then sends a note to tell the family they’ve been poisoned by his culinary cock-up. Silvio returns, this time in the guise of Dr Miracle, previously dismissed by the Mayor as a quack, to administer the ‘cure’. So, pleased is the Mayor that he allows the unmasked Silvio to marry his daughter.

If the tale is a trifle, Bizet’s music sparkles. And, Roberto Recchia’s production fizzed along merrily with characteristic wit and satirical style, and the extensive dialogue flowed smoothly. Luca Dalbosco’s straightforward set divided the stage into dining-room and lounge, with a wheel-on ‘kitchen’ providing a focus for the operetta’s musical highlight: the omelette quartet during which – as the salivating diners whipped themselves up in an ecstasy of gustatory anticipation – Guy Elliott’s Pasquin deftly stirred, whisked and seasoned, and delivered the offending outcome to the table.

Guy Elliott (Pasquin) and Lizzie Holmes (Laurette). Photo credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Guy Elliott (Pasquin) and Lizzie Holmes (Laurette). Photo credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Elliott was a pugilistic Pasquin and relished the physical theatre; he threw himself over sofas and tables with aplomb, and his tenor was no less agile. Simon Mechli?ski used his eyebrows and voice with equal expressiveness as the patriarch who is outgunned by his womenfolk and servants but who likes to maintain a veneer of imperious command. As Laurette, Lizzie Holmes’s light, lithe soprano was complemented by strong theatrical characterization, while Kasio Balejko’s warm, plump mezzo made her an excellent foil as Laurette’s stepmother, VÈronique – painting her nails during her adopted charge’s melancholic romanza, her hugs heaving with insincerity. Doctor Miracle may be slight, but it was slickly delivered here; an amusette and operatic amuse bouche far more appetizing that Pasquin’s poisonous pancake.

Rachel Goode (Maguelonne), Cecilia Gaetani (Armelinde), Isolde Roxby (Marie) and Richard Shaffrey (Le Prince Charmant). Photo credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Rachel Goode (Maguelonne), Cecilia Gaetani (Armelinde), Isolde Roxby (Marie) and Richard Shaffrey (Le Prince Charmant). Photo credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Davide Garattini Raimondi’s production of Pauline Viardot’s Cendrillon, first seen in April 1904 in the Salon of Mademoiselle de Nogueiras, a former pupil of Viardot, was not quite so convincing, principally because Luca Dalbosco’s set – piled up boxes, trunks and up-turned cobwebby lampshades in the (abandoned/dilapidated?) Hotel Viardot – seemed an unlikely domestic locale for Le Baron de Pictordu – the grocery boy made good who now lives a life of wealthy inertia and idleness. Plastic sheets, slightly torn and grubby, and hung across the length of the platform, marked a shift to the ‘palace’ of Prince Charmant – though as Marie/Cendrillon gleefully flung first pumpkin then mousetrap over her shoulder and beyond the sheets, Johann Fitzpatrick’s illuminated silhouettes deftly signalled a magical transformation to gilded coach and footmen.

Mark Bonney (Le Comte Barigoule) and Ben Watkins (Le Baron de Pictordu). Photo credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Mark Bonney (Le Comte Barigoule) and Ben Watkins (Le Baron de Pictordu). Photo credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Viardot came from a family of singers – her father was Manuel Garcia Senior, the Spanish tenor for whom Rossini composed the role of Count Almaviva, her older sister was Maria Malibran – and so it’s no surprise that she gives her cast some elegant and eloquent music to sing. Isolde Roxby was a wonderfully ‘genuine’ Cendrillon, delivering the sung and spoken text assuredly, with thoughtful interpretative gestures and a beguiling sweetness of character and tone. As her ghastly, grasping sisters, Cecilia Gaetani (Armelinde) and Rachel Goode (Maguelonne) were garbed in suitable garish red-and-green frocks and sang with glamorous gusto and vibrancy. Mark Bonney enjoyed his ‘prince-for-a-day’ sojourn, singing with pleasing tone and dramatic conviction, while Richard Shaffey’s Prince was indeed charming. Ben Watkins’ Baron was no mere caricature, some subtle vocal inflections adding a sharper, spicier edge.

Cinders’ Fairy Godmother – here, a real estate agent, whose quill served both to record the hotel inventory and to raise the spirit of magic – was sung by Kelli-Ann Masterson from Gorey, a recipient, alongside tenor Andrew Masterson from Omagh, of the PwC Wexford Festival Opera 2019 Emerging Young Artist Bursary Award. Masterson’s soprano gleamed with a cool transparency matched by the FÈe’s self-composed manner when instructing and guiding her charge.

Kelli-Ann Masterson (La FÈe). Photo credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Kelli-Ann Masterson (La FÈe). Photo credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Rodula Gaitanou’s production of Massenet’s Don Quichotte opened this year’s Festival, on 22nd October, but I saw the second performance in the run – and I was glad that I had, as this enabled me to enjoy the lunchtime recital presented in St Iberius Church by Georgian bass Goderdzi Janelidze (when he was accompanied by WFO’s Head of Music Staff, Andrea Grant) before I heard Janelidze embody Cervantes’ aging, noble dreamer in the O’Reilly Theatre. For, while Janelidze’s lunchtime programme perhaps lacked stylistic diversity – his chosen arias from Don Carlos and Simon Boccanegra, songs by Tchaikovsky and Georgian folksongs, alongside Don Quichotte’s Act 5 death-bed apotheosis all leaning towards the serious and melancholic – it offered the listener an opportunity to hear and relish the soft-grained potency of his powerful bass, its lyrical warmth, its mellifluous fluency, its animation where apt, its directness and immediacy.

Goderdi Janelidze (Don Quichotte) and Olafur Sigurdarson (Sancho). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Goderdi Janelidze (Don Quichotte) and Olafur Sigurdarson (Sancho). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

And, thus, Janelidze’s performance as Don Quichotte was revealed as a dramatic and expressive tour de force, a remarkable embodiment of nostalgia, nobility and gentility communicated physically and vocally. The ravages of time made their presence felt in Janelidze’s physical frailty: the limbs that needed a gentle nudge to bend or straighten; the slow steps and graceful prod that propelled the gallant knight’s bicycle onwards. Somehow Janelidze had the discipline to restrain his vocal weight – though his projection is so strong that even a whispered phrase made its mark – for the dramatic highpoints which impress upon us the knight’s honour: the riposte to the bandits who attach and abuse him in Act 3, ‘Je suis le chevalier errant’, or his death-bed promise to the loyal Sancho, ‘Prends cette Óle’. These sudden moments of enrichening and colour were so much more telling for the grave and tender fragility within which they were framed. I was deeply moved, almost to tears, by Janelidze’s courage and conviction.

Goderdi Janelidze (Don Quichotte) and Aigul Akhmetshina (DulcimÈe). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Goderdi Janelidze (Don Quichotte) and Aigul Akhmetshina (DulcimÈe). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Icelandic baritone Olafur Sigurdason’s Sancho justly received the audience’s warm appreciation too. Sigurdason, loyally following his master on a Vespa, balanced a quasi-Falstaffian pride with sincere service and love. Russian mezzo-soprano Aigul Akhmetshina shone as DulcinÈe, her voice creamy and seductive, her dancing joyful and free. Her cruel rejection of Quichotte’s proposal of marriage – a rasping laugh, bordering on vulgarity – was instantly regretted, DulcinÈe’s honesty communicated with pathos but not self-pity.

Aigul Akhmetshina (DulcinÈe) and Chorus. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Aigul Akhmetshina (DulcinÈe) and Chorus. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Gaitanou and designer takis serve up, via the simplest means, a veritable visual banquet of Spanish spirit. Four wooden platforms spin and transform to create a fiesta fairground ruled by the Carmen-esque DulcinÈe, furnish the bandits with their hideouts, and taunt Quichotte with ‘giants’. Simon Corder’s lighting is hypnotically enchanting: purple merges with indigo, which slithers into emerald, then blurs into gold, then orange. Henry Grant Kerswell was a crude and callous bandit; Gavan Ring a virile but frustrated suitor of DulcinÈe. The Wexford Festival Chorus sang with tremendous heart and spirit, and during the interludes between the acts the Orchestra were given plentiful encouragement to shine by conductor Timothy Myers: there were more superb solos than there is room to mention, but the woodwind rose to the occasion and the cello solo which serves to foreshadow the Don’s demise was beautifully played. This Don Quichotte was a truly memorable way in which to end my visit to Wexford.

Claire Seymour

Bizet: Doctor Miracle (23rd October, Clayton Whites Hotel)

Laurette – Lizzie Holmes, VÈronique – Kasia Balejko, Silvio/Pasquin/Dr Miracle – Guy Elliott, The Mayor – Simon Mechli?ski; Stage Director – Roberto Recchia, Music Director – Andrew Synnott, Stage & Costume Designer – Luca Dalbsoco, Lighting Designer – Johann Fitzpatrick.

Vivaldi: Dorilla in Tempe (23rd October, O’Reilly Theatre, National Opera House)

Dorilla – Manuela Custer, Admeto – Marco Bussi, Nomio/Apollo – VÈronique ValdËs, Elmiro – JosË Maria Lo Monaco, Filindo – Rosa Bove, Eudamia – Laura Margaret Smith, Ninfe – Rebecca Hardwick/ Lizzie Holmes, Pastori – Meriel Cunningham/Emma Lewis, Dancers; Director – Fabio Ceresa, Conductor – Andrea Marchiol, Set Designer – Massimo Checchetto, Costume Designer – Giuseppe Palella, Lighting Designer – Simon Corder, Assistant Director/Choreographer – Mattia Agatiello, Chorus master – Errol Girdlestone, Orchestra and Chorus of Wexford Festival Opera.

Pauline Viardot: Cendrillon (24th October, Clayton Whites Hotel)

Le Baron de Pictordu – Ben Watkins, Marie (Cendrillon) – Isolde Roxby, Armelinde – Cecilia Gaetani, Maguelonne – Rachel Goode, La FÈe – Kelli-Ann Masterson, Le Prince Charmant – Richard Shaffrey, Le Comte Barigoule – Mark Bonney; Stage Director – Davide Garattini Raimondi, Music Director – Jessica Hall, Stage & Costume Designer – Luca Dalbosco, Johann Fitzpatrick – Lighting Designer

Andrew Synnott: La cucina & Rossini: Adina (24th October, O’Reilly Theatre, National Opera House)

Bianca (Sous-chef) (La cucina) – M·ire Flavin, Tobia (La cucina)/ AlÏ (Adina) – Manuel Amati, Camillo (La cucina)/Mustaf‡ (Adina) – Emmanuel Franco, Zeno (La cucina) – Sheldon Baxter, Chef Alberto (La cucina) – Luca Nucera, Adina (Adina) – Rachel Kelly, Selimo (Adina) – Levy Sekgapane, The Caliph (Adina) – Daniele Antonangeli; Director – Rosetta Cucchi, Conductor – Michele Spotti, Set Designer – Tiziano Santi, Costume Designer – Claudia Pernigotti, Lighting Designer – Simon Corder, Assistant Director – Stefania Panighini, Chorus master (Adina) – Errol Girdlestone, Orchestra and Chorus of Wexford Festival Opera.

Rossini: L’inganno felice (25th October 2019, Clayton Whites Hotel)

Isabella – Rebecca Hardwick, Duca Bertrando – Huw Ynyr, Batone – Thomas D Hopkinson, Tarabotto – Peter Brooks, Ormondo – Henry Grant Kerswell; Stage Director – Ella Marchment, Music Director – Giorgio D’alonzo, Stage & Costume Designer – Luca Dalbosco, Lighting Designer – Johann Fitzpatrick

Massenet: Don Quichotte (25th October 2019, O’Reilly Theatre, National Opera House)

La belle DulcinÈe – Aigul Akhmetshina, Don Quichotte – Goderdzi Janelidze, Sancho – Olafur Sigurdarson, Juan – Gavan Ring, Pedro – Gabrielle Dundon, Garcias – Elly Hunter Smith, Rodriguez – Dominick Felix, Footman 1 – Thomas Chenhall, Footman 2 – RenÈ Bloice-Sanders; Director – Rodula Gaitanou, Set & Costume Designer – takis, Lighting Designer – Simon Corder, Choreographer – Luisa Baldinetti, Chorusmaster – Errol Girdlestone, Orchestra and Chorus of Wexford Festival Opera.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Olafur%20Sigurdarson%2C%20Goderdzi%20Janelidze%20%26%20Aigul%20Akhmetshina%20title%20image.png

image_description=Olafur Sigurdarson, Goderdz Janelidze and Aigul Akhmetshina [Photo credit: Clive Barda]

product=yes

product_title=Massenet: Don Quichotte – Wexford Festival Opera, 25th October 2019

product_by=A review by Claire Seymour

product_id=Above: Olafur Sigurdarson, Goderdz Janelidze and Aigul Akhmetshina

Photo credit: Clive Barda