The Quebquois-born composer Claude Vivier – still largely neglected, despite many of his works having an almost fearless intensity entirely relevant for today – was the subject of a rare retrospective at London’s Queen Elizabeth Hall over three days in early May. I made just one of the concerts, but it included his masterpiece, Lonely Child, written in 1980, three years before Vivier’s death at the age of 34.

Everything about Claude Vivier’s life – including the predictability of his murder – saturates his work. His legacy is not a large one, but it is a mirror of his past. He grew up in a Catholic orphanage in Montreal and throughout his life he would be haunted by the loneliness of being parentless. Many of his compositions – perhaps an over-proportionately large number of them – are for solo – or very few – instruments. He rarely writes for large orchestral forces although entire pieces use percussion and timpani – indeed, they play an important – devastating – part in Lonely Child. Although he would rebel against his Catholic upbringing and find Quebec oppressive those early years would shape his later ones in Europe, and especially Paris where he would ultimately spend the rest of his short life.

It was in Montreal, however, that Vivier’s life would find that shape. He would nurture an interest in ritual there. Like many orphans, he would find a personal identity in creating something for himself that most children are already born with, a name and a family; and his sense of liberation was such that he held back nothing. He shared with the French novelist Jean Genet, for example, a complete openness about his homosexuality. But that wasn’t enough – it had to be a dangerous openness. He lived on the edge, bordering on the chaotic and careering towards a queer martyrdom. It was this which would lead to Vivier’s murder in March 1983 when he met a 19-year-old homeless trickster. His final, unfinished work Glaubst du an die Unsterblichkeit der Seele for voices and ensemble is astonishingly prognostic of his death. It was written three months before he died: “Sitting there I felt like something would happen to me that day … Then my eyes fell on a young man whose strange magnetism moved me deeply … I could not take my eyes off him … I told him my name was Claude. And without further ado he pulled a knife out of his black Parisian jacket and stabbed me right through the heart”. The circumstances of Vivier’s life were perfectly conjoined; he died alone in his Paris apartment, much as he had been born – as an orphan.

Not all Claude Vivier’s works, especially the two which we heard in this concert, Zipangu and Lonely Child – both from 1980 – identify musically from Vivier’s studies with Karlheinz Stockhausen. Lonely Child, in particular, is entirely original in Vivier’s output to date and its beauty is profound. But that ambient tone is shattered by some of the most cataclysmic chords for bells and percussion. When the music falls into silence it is to be disrupted by an earth pounding bass drum. In 1982, Vivier spoke of Mahler as the composer to whom he felt closest and these hammer-beats felt Mahlerian. The French libretto, too, is notoriously complex – and demanding. Its rhythm and meter rarely correspond to what you see on the page, and some vocal effects stretch beyond language. With Zipangu, however, Vivier is entering his ‘Marco Polo’ phase, a series of works centred on this figure and with whom Vivier would partly identify. Where he found introspection and inwardness in Quebec he would find a freedom and discovery in the Far East, especially Japan – ‘Zipangu’ being the name given to Japan in the time of Marco Polo. It’s a work for string orchestra but right from the opening bars you can almost smell the scent and hear the rituals of Japan beginning to start their journey through this magnificent score. This is, I think, more of a spiritual odyssey than in perhaps Shiraz, his work for piano solo, where it is the fascination with repetition that creates the musical picture. In Zipangu Vivier uses a singular theme but applies multiple bowing techniques to create a kaleidoscope of oriental colour.

It is unsurprising that the two performances by the London Sinfonietta of the Vivier works should have been as magnificent as they turned out. Vivier does not write long works – Zipangu in an average performance is roughly fourteen minutes long, Lonely Child not that much longer – but they need uncommon devotion to bring them off. Zipangu uses thirteen strings (7-0-3-2-1) and here it was the players’ skill in applying the pressure on their strings – rather than purity in the natural harmonics you might be expecting to hear – that impressed most. This is an orchestra where players listen to each other; where the performance drew its colour (and there is much of that in the score) from its chords and where its intricacies were unwound with revealing clarity. Ilan Volkov proved to be enormously expressive digging deep but allowing his players just the right amount of freedom. I’m not sure I have heard this music interpreted with more immaculacy and freshness than it was here. This was less a “played” performance – it was a white-hot interpretation created for the moment.

Much could be said of Lonely Child, the only work played after the interval. What one noticed first about the staging of this work was its visual depth – and much of this was applied to a vast percussion section which included a gong, a Chinese gong, tam-tam, bass drum, vibraphone, bells, a double woodwind section and a full-sized string section for chamber orchestra. The application of depth is entirely about the work’s timbre, a richness in the base line that evolves over the orchestra and into the audience like a vast swelling ocean of sound. Although the frequencies of music here can be controlled, they can often be monumental too. The bass drum may be solitary; it may be a singular voice but its sound seems to both explode and implode simultaneously with different effect.

Lonely Child seems to come from a different world. Without chords, harmony or counterpoint the orchestra becomes a series of frequencies transformed into its own timbre. What Vivier controls is the amount of colour it then gives off. It doesn’t sound ravishing in a kind of Ravel-like way simply because it eschews the way Ravel wrote his music – but it has all the diaphanous beauty of it. The colours are intense but not really as we perceive them. It all came down to the richness of tone of the Sinfonietta players. They may have been playing as an orchestra but you didn’t just hear it as one. The timbre very much came to depend on the instruments themselves, each having its own voice, each like a ‘Lonely Child’ within the orchestra. It may have been Paul Silverthorne’s voluptuous viola or Leva Kupreviciute’s brightly shining piccolo, for example.

Holding it all together, that real lonely voice, was the magnificent Claire Booth. This monologue requires something more than just a soprano – it needs a great actress to bring it off. The text of the work is every bit as full of colour as the orchestration itself – even its opening line takes us right into the kind of vocal dreaminess and timbre the voice is expected to express throughout this long piece: “Bel enfant de la lumière dors, dors, dors toujours dors.”

Where it becomes untranslatable – “Dadodi yo rrr-zu-I yo a-ei dage dage da è-i-ou” – the voice becomes an instrument itself with a hand placed upon the lips to create a sound. Booth was superb. Much of the text of Lonely Child speaks of dreaminess, magicians (Merlin), the stars, and fairies. It speaks of the child, of eternity and sleep. What Claire Booth brought to all this was a dreaminess to her singing as she seemed to create from this monologue a kind of single stream of consciousness. It isn’t written in this form, but for much of it Booth rarely seemed to attend to the broken structure of the text as she sung it in one great expressive arc. Those magnificent high tones Booth had, the purity of the voice itself seemed all the more vulnerable as they were shattered and broken by the huge gongs and bells that smashed their way through her monologue. It’s here that Lonely Child finds both an aura of intimacy and violent destruction. Claire Booth was that vulnerable child against that mighty force that proved to be Ilan Volkov.

It’s probably impossible not to look on this work, even as late as 1980, as semi-autobiographical. Claude Vivier’s life was so affected by the circumstances of his childhood that his music is talismanic of it even right up to the very day of his death. Great performances of his works are reminders of what a great composer he was – and these were unquestionably those kind of performances.

I found Nicole Lizée’s The Seeds of Solitude almost ruinous beside the two Claude Vivier pieces. It did share some things in common with Lonely Child but they were so narrow as to be exactly that. It’s a monologue, but mostly spoken or droned. Where it became vocal it didn’t fit into a particular theatrical or musical form. It implied that Claude Vivier was trying to communicate with his deceased mother via his music, too, which is at best speculative. But Lizée’s work is neither strikingly original nor is it well executed. It works as installation art with the music played against a background of a film in which a woman with a tape recorder references paranoia, insomnia, nostalgia and psychosis. When she receives a packet of seeds and grows them the results are unexpected – with dreamy, unsettling and vivid results. These were not convincingly done – the peeling back of fingernails like a sliding door, for example.

I felt no particular warmth towards a performance of this work that the London Sinfonietta and Ilan Volkov played with their usual skill.

This concert had been a reminder of the greatness of the work of Claude Vivier, a composer we hear less often in the UK than we should. In performances as magnificent and compelling as these it’s the reason why his music is by far the best reason to remember him than the tragic events surrounding his notorious murder which is still so often the case he is remembered today.

Marc Bridle

Claude Vivier – Zipangu (1980), Nicole Lizée – The Seeds of Solitude; Claude Vivier – Lonely Child (1980)

Claire Booth (soprano), Ilan Volkov (conductor), Simon Hendry (sound design), Royal Academy of Music Manson Ensemble, London Sinfonietta

Queen Elzabeth Hall, Southbank Centre, London; Friday 6th May 2022.

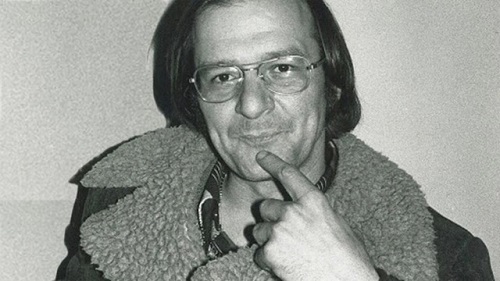

ABOVE: Ilan Volkov conducts the London Sinfonietta (c) Monika S Jakubowska