In 1906, Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924) published The National Song Book, a collection of folk-songs, carols and rounds. In an address to a musical society in 1917, Arthur Somervell – who had been appointed His Majesty’s Inspector with responsibility for music in 1901, a position he held until 1928 – declared that there was not a school in the country that did not possess a copy of The National Songbook.

In his article, ‘Towards the National Song Book: The History of an Idea’, Gordon Cox has explored the relationship ‘between music and national feeling [which] permeated popular music education during the latter half of the nineteenth century’, noting that ‘music educationists developed distinct theories about the educative value of such songs in developing notions of nationhood, patriotism and racial pride’.[1] Such theories developed as the growth in imperial nationalism in the late 19th century coincided with the 1870 Education Act which provided a school place for every child; ten years later school attendance would become compulsory.

There had been earlier national song books, the most significant of which was Popular Music of the Olden Time (1858-59) by the William Chappell, a member of the eponymous music publishing business. It contained 400 hundred airs arranged chronologically, and – as Cox points out – in prioritising literary and printed sources, and excluding balladry, it anticipated Stanford’s own emphasis on the national song as part of a literate, rather than oral, tradition – a position which brought him into conflict with Cecil Sharp, who published his own A Book of British Song for Home and School in 1902. Stanford acknowledged his debt to Chappell and declared his belief that his national songs reflected English qualities such as ‘patriotism, self-reliance, constancy in love and friendship, good humour, good fellowship and brotherly kindness’. A Professor of Music at Cambridge from 1887, and one of the founding members of the Royal College of Music, he was a leading figure in the ‘English musical renaissance’, and believed that schools were crucial in the revitalisation of music, telling the managers of the London Board Schools in 1889, ‘In music you have at your disposal the most powerful living agency for the refinement of the masses’.[2]

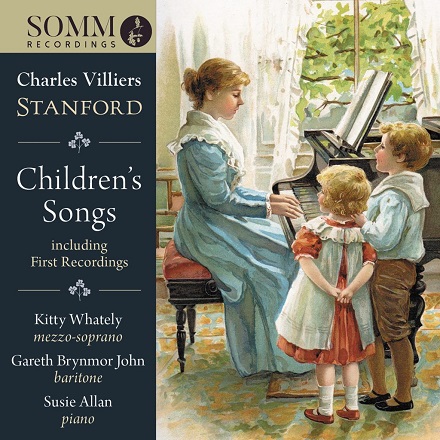

Jeremy Dibble – in his informative liner notes to this new recording of Stanford’s Children’s Songs by mezzo-soprano Kitty Whately, baritone Gareth Brynmor John and pianist Susie Allan, on the SOMM label – explains that alongside folk-song arrangements, The National Songbook included a substantial repertoire of original songs by Stanford, conceived for children’s voices and characterised by ‘melodiousness, memorability, the sympathetic wedding of words to music … harmonic and textural simplicity, technical pragmatism and vivid imagery’.

This disc offers a valuable opportunity to hear these songs, many of which are recorded for the first time. The melodiousness that Dibble remarks is strongly evident in the opening group, A Child’s Garland of Songs Op.30, which sets nine poems from Robert Louis Stevenson’s Children’s Garden of Verse. Brynmor John’s relaxed baritone is immediately engaging, and he introduces just the right touch of expressive heightening, avoiding affectation but infusing the songs with an air of adventure and excitement – as when, at the end of ‘Bed in Summer’, the poet-speaker wonders why, when the sky is clear and blue, and he should so much like to play, he has “to go to bed by day?” Or, when the view of pleasant places never seen before, in ‘Foreign Lands’, inspires a vocal surge and, aided by Allen’s rippling accompaniment, the real and the fantastical merge in the poet’s eye. Or, when the light humour of ‘My Shadows’ mutates to magic in the slow final stanza as, venturing out very early before dawn, the poet-narrator strangely shakes off his “lazy little shadow”, which stays at home “fast asleep in bed”.

The baritone’s lovely lyricism in ‘Where go the Boats’ captures the intensity of childhood play, as the young lad imagines his boats sailing off down the river, to be brought home by other children, hundreds of miles away. Elsewhere it’s the piano that sharpens the tension, and Susie Allan gallops on a taut rein in ‘Windy Nights’. Some of these songs were later arranged for vocal duet, and Brynmor John is joined by Whately in ‘Pirate Story’ – where Allan’s cheery accompaniment is made more sophisticated by asymmetrical phrasing in the vocal lines and rich splashes of poetic imagery – and in ‘Marching Song’, where her bright, clear mezzo-soprano adds a fitting ‘lift’ to the military beat.

Born in the north-east of Scotland, the daughter of a Presbyterian minister, Helen Douglas Adam (1909-93) moved to America in the 1930s where she became, in the words of literary scholar Brenda Knight, a ‘bardic matriarch’ to the San Francisco Beat poets. Her work was included in Donald Allen’s seminal collection, The New American Poetry 1945-1960, and she later ventured into other artistic fields, such as experimental filmmaking and opera. However, her reputation was founded on her grasp of the power of the ballad forms of her native land, an interest which was evident in The Elfin Pedlar and Tales Are Told by Pixie Pool, a collection of fairy ballads and nature poetry which she published when she was just 14 years old. Though decorous rather than dark, they appealed to Stanford’s fascination with the land of faerie and he selected twelve poems which were published in two sets of six, titled Songs from ‘The Elfin Pedlar’.

Whately sings the first volume, her voice radiating with apt lightness. As Allan sensitively draws out the harmonic nuances, the mezzo-soprano captures the preciousness of the close of ‘Two Little Stars’, with its wondrous image of “two star babes” that fall from the evening sky and make a nest in a new babe’s eyes. The maid’s excited entreaties in ‘The Pedlar’ are countered by the eponymous traveller’s poignant tale of his quest for a child stolen by the fairies. Stanford’s brief delicately tumbling repetitions in ‘Little Snowdrop’ perfectly capture the bright energy of Adam’s anaphoric miniature, while ‘Speedwell’ is particularly lovely: Allan makes the elves skip and the butterflies gleam, and the poet-speaker’s awed questioning – “Are you fairies’ kisses sweet,/ Scattered down beneath our feet?” – gently glows with love.

Brynmor John is equally affecting in the second set, distinguishing in ‘What do you see?’ between the puzzled probing of the first speaker and the invigorated response of the child who sees fairies in the shadows, swinging on silver bells, dancing mermaids in the river reeds, and a fairy queen in the daisy. The tender elongation of the closing phrase, “When the fragrant breeze is lazy”, slips dreamily into the otherworld. In ‘The Piper’, the baritone captures the ardour of the post-speaker’s longing for a glimpse of “the piper in the woodland, the piper of the Spring”. The humming bees of ‘Summer’ pirouette with carefree joy, while the eponymous ‘Dust-Man’ approaches with a spring in his silent step, ready to scatter his sleep-dust with its promise of dreams. In contrast, ‘The Secret Place’ and ‘Night’ are melancholy musings which Brynmor John sings with discerning feeling.

The Fours Songs Op.112 and Six Songs Op.175 were not all specifically designed for children, though they retain something of the melodic directness and natural eloquence that characterises the children’s songs. The former set poems by Tennyson. In ‘Spring’ the chirpy ephemeralness of “Birds’ love and birds’ song”, is strengthened into something more mature and ardent by Brynmor John when reflecting on “Men’s song and men’s love,/ To love once and for ever”, and Stanford finds a musical innocence which overcomes the rather cloying sentimentality of the poet’s ‘The City Child’. Whately and Allan imbue ‘The Silence’, which considers the mystery of Lazarus’s raising by Christ, with a well-judged earnestness and thrilling luminosity, which is matched by the personal intensity of ‘The Vision’, in which the gentle meanderings of the low piano expand with the fervent vocal line – beautifully phrased by Whately – into a moving expression of grief for Arthur Hallam.

Of the Op.175 set, ‘A Song of the Bow’ rollicks with a merry swing, Brynmor John again inflecting key phrases with colour and weight, and drawing out small details such as the amplifying melisma – “Earth is green and Heaven is grey,/ Wherefore should we not be jolly”. Allan seals the song with a flourish that enhances the buoyant immediacy. In such ways, simple lyrics and melodies gain a richness that makes them shine brightly. Wriggling piano gestures add a frisson of sensuality to Whately’s glistening rendition of ‘Drop me a Flower’, another Tennyson setting, while she enjoys the melodic dignity of the Christmas song, ‘The Winds of Bethlehem’, expanding beautifully with the vision, “They saw the Maker of the World”, then retreating into calm to reflect on the adoration new King, “so small and sweet”, bestowed by winds from the four points of the compass. I particularly like ‘Lullaby’, a setting of George Levenson-Gower (1858-1951): Allan’s airy accompaniment is tender and eloquent, and Whately lightens her mezzo beautifully, phrasing most sensitively and infusing the mother’s loving entreaty, “Slumber my sweet one, slumber my daughter”, with persuasive feeling. The final soft urgings, “slumber and sleep”, are wonderfully comforting.

The disc concludes with seven individual songs, several of which were published in educational collections such as Novello’s The School Music Review and Edward Arnold’s Singing Class Music. Whately delights in the lurid imagery of ‘Witches’ Charms’, the shine in her mezzo conjuring the ghastly glee of the spiteful spell-makers, while Allan’s stripping staccatos and crystalline motifs add to the carefree optimism of ‘Fairy Lures’, with its unwavering faith in the luck that fairies bring. Brynmor John’s expressive lower register conveys the poet-speaker’s pressing fixation on the memory of “flashing white fetlocks all wet with the dew” and the clatter of iron-shod hooves that thunder ceaselessly through his mind, waking and asleep, in ‘The Hoofs of the Horses’ – the galloping echo made vividly palpable by the resounding melisma in the closing line. ‘The King’s Highway’ – a setting of Henry Newbolt which was first performed, in an orchestrated version, by Robert Radford at a Proms Concert in the Queen’s Hall in September 1914, conducted by Henry Wood – makes for a rousing end to the recital, Brynmor John robustly conveying the song’s patriotic heft and vigour.

This is a generous disc. As always, the SOMM engineers have ensured the sound is clear and well-balanced. Brynmor John, Whately and Allan make these songs utterly involving. Just one small thing: the disc cover should certainly say, ‘Not just for children’.

Claire Seymour

Stanford: Children’s Songs

A Child’s Garland of Songs Op.30, 4 Songs Op.112, 6 Songs Op.175, Songs from the Elfin Pedlar Book 1 Op.post., Songs from the Elfin Pedlar Book 2 Op.post., ‘Witches’ Charms’, ‘Summer’s Rain and Winter’s Snow’, ‘Fairy Lures’, ‘The Hoofs of the Horses’, ‘A Japanese Lullaby’, ‘Worship’, ‘The King’s Highway’

SOMMCD 0655 [78:46]

[1] Gordon Cox (1992) ‘Towards the National Song Book: The History of an Idea’, British Journal of Music Education, 9(3), pp.239–53.

[2] C.V. Stanford (1908) Studies and Memories. London: Archibald Constable.