Seattle Opera has long championed the operas of Richard Wagner. Legendary impresarios Glynn Ross and Speight Jenkins – the latter, at 85, still cutting a dapper figure in the audience this week – established Seattle as one of the few places outside of Bayreuth where one could regularly hear summer Ring cycles, hear every one of Wagner’s operas, and attend an international Wagner signing competition.

While the company has retrenched somewhat in recent years, it remains committed to its Wagnerian roots. Enthusiastic audiences are packing McCaw Auditorium for the company’s new production of Tristan und Isolde.

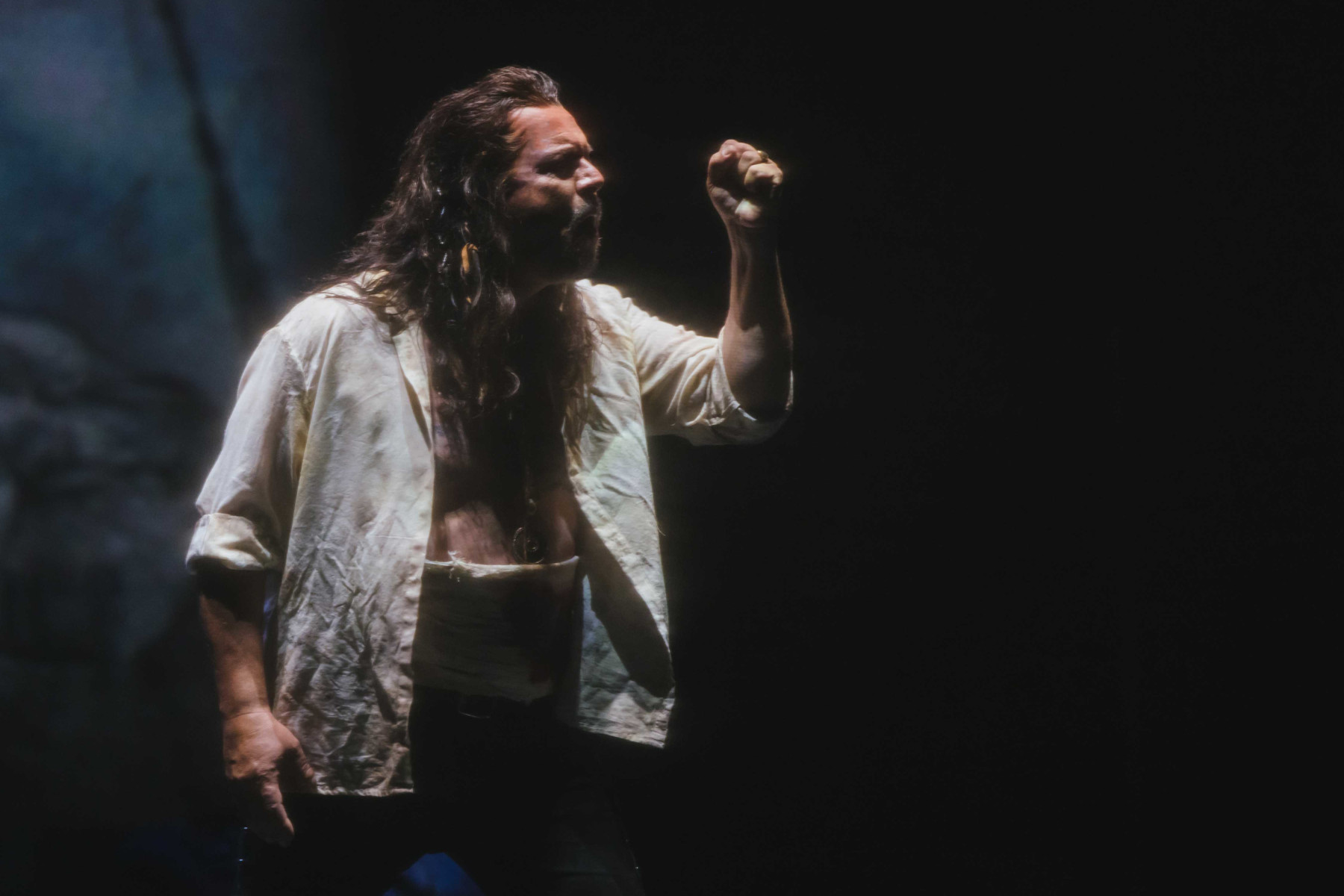

German Heldentenor Stefan Vinke, who sings smaller roles in major houses, shares top billing with American soprano Mary Elizabeth Williams, who makes her role debut as Isolde. Both possess an essential quality rare these days: the vocal heft to cut through the orchestral sound to the back of a large hall.

Yet, on the night I attended, both struggled technically – in part because of the strain of pushing smaller voices to fit these outsized roles. Vinke sang many extended passages flat, and the vocal timbre in the upper voice, though often brilliant, often lacked the requisite baritonal weight and color.

Williams, clearly far less familiar with Wagnerian style and diction to start with, fought an unevenness of vocal registers. At forte, passages in the upper middle portion of her voice curdled and hardened, while many lower-lying passages disappeared entirely. Perhaps to combat this, Williams tended to slide or scoop into notes, thereby even further distorting the musical line and German diction. Sung in this way, Isolde’s climactic Liebestod remained earthbound rather than transcendent.

Both singers faced the greatest challenges in Act II, where the long love duet demands loud, agile, and coordinated singing beyond their ability. Elsewhere, however, they offered moments of powerful interpretive insight.

Most moving of all were the Act III monologues, with their lighter orchestration, during which Vinke’s mellowed his timbre and delivered the full intensity of existential suffering that underlies Tristan’s romantic passion. For her part, Williams also excelled in quieter passages, when her voice gained focus – something that suggests that Wagner singing does not come naturally, but requires that she force her voice.

By contrast, Amber Wagner’s Brangäne illustrates the vocal ease, richness, and power once taken for granted in Wagner singing and now almost extinct. No other Wagnerian singer today can match her ability to flood large spaces with warm, evenly-produced tone, while projecting intelligible German. She sings from the heart, and thus it would perhaps be a quibble to point out that a bit more dynamic restraint and an instrumental tone quality might better suit this supporting character.

Other characters were engagingly cast. Baritone Ryan McKinney brings vivid shades of dynamics and color to Tristan’s stolid squire Kurwenal. Tenor Viktor Antipenko sings assertively while avoiding the stridency that often tempts those cast as treacherous Melot. Morris Robinson possesses a deep and even bass voice but has yet to command the legato phrasing and hushed tones that allow König Marke’s two melancholy monologues to dig deep. Tenor Andrew Stenson’s well-projected Sailor, opened the opera uncommonly well, not least because the staging dictates that he sing from within the theater. The other characters on stage stared out into the house as if wondering whence the sound comes – a reminder that this is diegetic music that the characters hear, not Wagner’s orchestral evocation of their interior life.

Conductor Jordan de Souza is a 35-year-old Canadian prodigy. He has already moved through career phases as a virtuoso organist and a Baroque choral conductor, and now heads the prestigious Komische Oper Berlin and globetrots as an opera conductor. His crisp cues, rhythmic flow, and ability to create a transparent and delicately balanced soundscape signal remarkable self-assurance in someone conducting this difficult score for the first time. A decade from now, he may well be hailed as one of the greats among modern opera conductors – and I imagine that he will develop a firmer command of this opera’s climactic moments. The orchestra responded splendidly through the night – with the despondent English horn solo in Act III more beautifully phrased than I have ever heard.

The new production directed by an Argentinian team led by Director Marcelo Lombardero rests on a sound premise, namely that Tristan and Isolde inhabit a world that exists only for them – and a world that we can glimpse only dimly through the myths we construct about them. Certain moments succeed brilliantly, notably the act-ending freezes of silhouetted figures, as if the story is becoming an epic legend before our eyes. Also, the sets reflect ample sound back into the hall – an essential acoustical detail too many modern productions neglect. Elsewhere, however, Stage Designer Diego Siliano might rethink the projected drawings of medieval kitsch, videos of “passionate” waves, clumsy mechanical scene changes, and an annoyingly invasive scrim.

Andrew Moravcsik

Tristan und Isolde

Music and libretto by Richard Wagner

Cast and production personnel:

(In order of appearance) Sailor/Shepherd: Andrew Stenson. Isolde: Mary Elizabeth Williams. Brangäne: Amber Wagner. Kurwenal: Ryan McKinny. Tristan: Stefan Vinke. Melot: Viktor Antipenko. King Marke: Morris Robinson. Steersman: Joshua Jeremiah.

Conductor: Jordan De Souza. Stage Director: Marcelo Lombardero. Set & Video Designer: Diego Siliano. Lighting Designer: Horacio Efron. Costume Designer: Luciana Gutman. Video Animation: Matías Otálora. Chorusmaster: Michaella Calzaretta.

Above photo: (L to R) Mary Elizabeth Williams as Isolde and Amber Wagner as Brangäne. Photo credit: Philip Newton.