Goerne programmes are always imaginative, bringing out new perspectives, enhancing our appreciation of the depth and intelligence that makes Lieder such a rewarding experience. Menahem Pressler is extremely experienced as a soloist and chamber musician, but hasn’t really ventured into song to the extent that other pianists, like Brendel, Eschenbach or Richter, for starters. He’s not the first name that springs to mind as Lieder accompanist. Therein lay the pleasure !

Goerne and Pressler walked onto the Wigmore Hall platform arm in arm, because Pressler, at 91 years of age, needs a bit of support to walk. But there was no mistaking the warmth of their relationship. Although they’d planned to end their recital with Schumann Dichterliebe op 48, they made a last-minute decision to place it first, for reasons that became clear later.

Dichterliebe was Schumann’s gift of love to Clara, celebrating their marriage after years of opposition, which included civil litigation against her father. Hardly a “normal” courtship. It’s hardly surprising that music poured out of Schumann in a torrent of excited ecstasy. This Dichterliebe was decidedly individual. The pace was brisk, the songs flowing into each other, highlighting the sudden, extreme swings of mood from one song to another almost colliding. Die Rose, die Lilie, die Taube felt almost manic. Goerne’s voice is flexible enough that the words tumbled out effortlessly even though the pace suggested tongue twister: “Die kleine, die Feine, die Reine die Eine”. On paper, Heine;’s poems are impressive, but Schumann’s settings add a filter which is highly individual, and not comfortable. They are big “R” Romantic, rather than coy, little “r” romantic. There’s a huge difference.

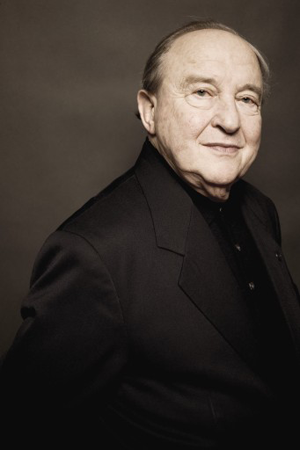

Menahem Pressler

Menahem Pressler

Goerne’s Ich grolle nicht chilled the heart. “I bear no grudge” the text insists, but Goerne’s growl in the word “grolle” grates with menace. The “s” and “z” sound in the phrase “und sahe die Schlang’, die dir am Herzen friflt.” bit with venom. It’s ironic that so many of the songs in this garland of love deal with grief and loss, the “dream” songs the most unsettling of all, with their intuitive grasp of subconscious forces. Pressler’s approach was unorthodox, but psychologically astute. Most Lieder fans have heard so many Dichterliebes in the past that this very singular interpretation was much more interesting than something safe or standard.

Picking up on the theme of dreams in Dichterliebe Pressler then played Schumann’s Variations on a theme in E flat WoO 24, the Geister Variations” (1854) Written a week before Schumannn tried to drown himself in the Rhine, the variations are based on a theme he had dreamed about, telling Clara that he’d heard it sung by angels, and telling a friend that it had been sent to him by Schubert. One thinks of the half-forgotten dream in Alln‰chtlich im Traume in Dichterliebe, with its phrase “….und’s Wort hab’ich vergessen”. The sombre hymn-like mood reflects that of Im Rhein, im heiligen Strome from Dichterliebe. Heine’s text links the image of the Virgin Mary with the idea of the poet’s lover. But Schumann’s setting is inexplicably dark and ponderous, describing the waves of the river as ominous forces. In the context of what was happening to Schumann when he wrote the Variations, the hypnotic pull of the waves in the song is chilling.

This theme of delusional grandeur also puts Schumann’s op 89 (1850), settings of poems by Wilfried von der Neun, “Wilfred of The Nine”, meaning the nine muses, no less. This was the glorified pseudonym, allegedly adopted in his early youth by Friedrich Wilhelm Traugott Schˆpff (1826-1916) who made a living as a pastor in rural Saxony. The poems are pretty banal, far lower than the standards Schumann would have revered in his prime. However, bad poetry is no bar, per se, to music. As Eric Sams wrote “the inward and elated moods of the previous year mingle blur together in the new chromatic style in the absence of diatonic contrasts and tensions a new principle is needed. Schumann accordingly invents and applies the principle of thematic change….It is as if he had acquired a new cunning and his mind had lost an old one.”

Sams is the source to go for studying these songs, since he analyses them carefully, drawing connections in particular to Am leuchetenden Sommermorgen and Hˆr’ ich ein Liedchen klingen in Dichterliebe. Sams said “Schumann’s memory is playing him tricks”. By pairing these songs with the Geister Variations, Goerne and Pressler are making a powerful case for coming to terms with Schumann’s later work. Texts like Es st¸rmet am Abendhimmel lend themselves to dramatic treatment but it would be wrong to suggest that they should be performed as faux Wagner. Schumann knew very well who Wagner was, but he had his own ideas about musical drama. which we need to respect if we are to fully appreciate his place in music history. Goerne and Pressler know their Schumann well enough to let us hear Schumann as Schumann, without distortion or special pleading. These may not be Schumann’s finest moments, but they’re still authentic and personal. Because this performance was so good, and so sensitive to Schumann’s inner world, we could understand something, perhaps of what Schumann might have been going through in his long last illness. In Ins Freie, the poet cries out “Mir ist’s so eng all¸berall!” He imagines he can escape “aus d¸strer Mauern bangem Ring “ through songs. But the song ends with the same frustrated cry, which Goerne sang with heartfelt anguish, not play-acting histrionics, but sincere identification with the frustration Schumann might have felt as his mind closed in on him.

Schumann’s Poems of Nikolaus Lenau op 90 (1850) were written in August 1850, barely three months after the von der Neun set, but are altogether more accomplished, since the poetry of Lenau (1802- August 22nd 1850) was on a level to bring out the best in a composer extraordinarily responsive to good literature. The poems Schumann set were published in 1838, so Schumann would have known him as a contemporary and heard of the psychotic attack Lenau suffered in 1844, which led to his being incarcerated in an asylum for the rest of his short life. Promise, cut down too soon: rather uncomfortably close to Schumann’s own situation.

Die Sennin is beautifully lyrical,with lilting harmonies that evoke warm breezes and the freedom of nature. One can almost imagine cow bells. The girl sings so beautifully that even the Felsenseelen (the souls of mountain rocks) echo her song. One day she’ll be gone but her songs live on in the memory of the crags. In Eisamkeit, silence hangs over a forest, Herz (the poet’s) is alone. Pressler plays the circular forms in the piano so they cradle Goerne’s tenderly. “Deine Lieber Gott versteht”

Leaving Schumann’s Requiem which rounds off Op. 90 off the programme worked out well, as it concentrated attention on Dichterliebe and on its connections with the lesser-known late works, and on Schumann’s inner life. In any case, the text is not Lenau. Since the mid 19th century, we’ve learned more about mental illness and can be more understanding. I wish, however, that Goerne and Pressler had done Lied eines Schmeid (Op 90) A little horse never lets the blacksmith down. Its steady trudging rhythm may seem simple, but in its own charming way, it’s a hymn for the faithful. To a horse! In its sincerity, it would have been a happy coda to Goerne and Pressler’s sensitive approach to Schumann’s later years. The concert was being recorded. Goerne and Pressler will repeat it at the Verbier Festival on July 22nd.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/GOERNE_Borggreve006.gif

image_description=Matthias Goerne [Photo by Marco Borggreve]

product=yes

product_title= Robert Schumann, Matthias Goerne and Menahem Pressler, Wigmore Hall, London 2nd July 2015

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=Above: Matthias Goerne [Photo by Marco Borggreve]