Opera Holland Park have given us three smashing productions so far this season (Iris;La bohËme;La Cenerentola) and this new production of Strauss’s champagne-fuelled Die Fledermaus, directed by Martin Lloyd-Evans, fizzes along like a glass of bubbly.

Lloyd-Evans pulls off the trick of balancing tongue-in-cheek farce with dramatic credibility. Rather than the inanities of a Carry-On caper, this

show presents a romp with the wit and sparkle of an Ayckbourn farce enjoyed in a seaside theatre in mid-summer.

It’s true that there’s little of the ‘darkness’ which casts a subtle shadow over Strauss’s escapist fantasy. And, for those who remember Christopher

Alden’s 2013 ENO production, which buried the fun beneath Freudian symbolism and envisaged the protagonists as psychiatric case-studies, that might be a

good thing. But, there’s little sense of Viennese nostalgia either. Strauss may have recreated the debonair congeniality of aristocratic life in fin-de-siËcle Vienna, but the world he presents was resting on a precipice: the ‘fall’ to come was swift and deep, and the operetta spares neither

working-class ambition nor the apathy, frivolity and superciliousness of the Viennese elite in a time of economic and political uncertainty. Alfred’s

seductive plaint to Rosalinde, ‘Happy are those who forget that which cannot be changed’, might be seen as a comment on bourgeois attitudes following the

stock-market crash of 1873.

Act 1: Ben Johnston (Eisenstein), Robert Burt (Dr Blind), Susanna Hurrell (Rosalinde)

Act 1: Ben Johnston (Eisenstein), Robert Burt (Dr Blind), Susanna Hurrell (Rosalinde)

What we have instead is stunningly lit (Howard Hudson) Art Deco decadence. Designer takis replaces the curves of Art Nouveau with the angles of Art Deco,

and in Act 1 uses elegant glass and metal screens to partition the stage, thereby creating the Eisensteins’ intimate but uncluttered boudoir and bathroom.

With the extant walls of the Elizabethan Holland House visible in the background, the effect was the blend of medieval royal palace and cutting-edge

modernity that one finds at Eltham Palace, the colour-schemes of which takis’ palette recalled. The design was economical too. The screens were swivelled

to expose the Holland House portico and entrance steps, and a pyramid of champagne coupes, a trio of round gold pedestals, heaps of sumptuous pillows, and

a sprinkle of some topless male waiters, bunny-girls and cross-dressing revellers transported us from private chamber to public ballroom. Prince Orlofsky’s

palace was an ironic meeting-place of burlesque and Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut.

The Opera Holland Park Chorus were once again superb in this Act 2 ball scene, the vocal precision and vitality even more impressive as Adam Scown’s slick,

detailed choreography kept them busy. They were naturalistic as party-goers and showman-like as whirling dancers. They were permitted a brief rest during

the ballet sequence in which burlesque dancer Didi Derriere (yes, really) tickled their fancies with a beguiling ostrich-feather fan display.

After the carousing highs of Act 2, the final act always struggles to maintain momentum and a distinct hang-over pall descended in Act 3, as the glittering

screens and colours faded to leave us in grey prison, sparsely adorned with desk and filing cabinets. Ingeniously, though, we were afforded a glimpse into

the cells where the merrymakers slept off the excesses of the night: stage-right, a square-patterned frame which had lurked in the distance all evening,

inconspicuously according with the general design, was now brought the fore and populated with inebriate-strewn mattresses.

Lloyd-Evans’ slapstick requires nimbleness and good comic timing from his cast, and they oblige. Prison governor Frank – sporting a Clousseau mac – can’t

enter a room without tripping over the doorstep and ends up asleep with his head in a bucket; horse-play with cuff-links and overcoats repeatedly leaves

the characters tied in knots. Alfred’s attempt to infiltrate his beloved’s bedchamber via a ladder is thwarted, time and time again, by a slamming of the

window: what could have been hackneyed instead became the delightful fulfilment of expectation – was it my imagination, or was there a slightly longer,

playfully teasing, delay before each successive crash? The ‘off-kilter choreography’ of the four Keystone Cops who accompany Frank to arrest Eisenstein is

charming – as is the bashful smile of the fourth, and somewhat tardy, diminutive copper. Their bobbing and baton routines, their over-swift departure and

sheepish return, last just long enough to tickle without irritating. And, it takes a lot of practice to get the sequences that ‘wrong’.

The farce is aided by Alistair Beaton’s rhyme-wielding translation. The verbal gags are engagingly modern but in keeping with the spirit of the original.

And who could fail to be impressed by the blustering Dr Blind’s neologistic invention: ‘magnifying’, ‘modifying’, ‘ratifying’, ‘verifying’, ‘speechifying’,

‘simplifying’, classifying’, ‘disqualifying’ […] ‘alibi-ing’! The spoken dialogue came across well, the Eisenstein’s RP contrasting with Falke’s Irish

brogue. Adele’s neat switch between Home Counties and northern working-class exemplified her social aspirations and get-up-and-go.

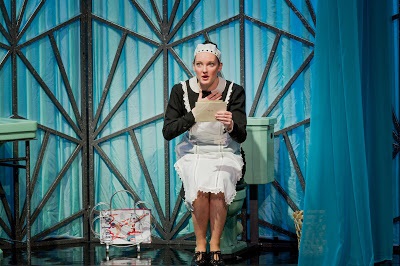

Indeed, as Jennifer France perched in Eisenstein’s bathroom excitedly poring over the invitation from her sister, Ida, to attend the Prince’s ball, it was

clear that this was a chambermaid who knew her own mind and was going places. France negotiated the bravura coloratura with ease and the Act 2 ‘Mein Herr

Marquis’ was a dramatic and musical delight: unceremoniously spun and dumped into a pile of cushions, Ben Johnson’s Eisenstein was no match for this sassy

lass.

Jennifer France (Adele)

Jennifer France (Adele)

Johnson and Susanna Hurrell were a good comic duo in Act 1 and the Act 2 seduction-duet was fun, as Hurrell taunted her frustrated, belittled husband with

his pocket-watch. Johnson has an elegant voice, but it is quite light, though nimble and warm; I’d have liked a bit more authority – after all he is the

‘master’ of the house – but he stamped his presence more forcefully when convincingly disguised as Dr Blind. Hurrell’s Rosalinde was glamorous in a

rose-pink pyjama suit and exotic in a fabulous green-and-gold get-up as the Hungarian princess. This was a winning impersonation, full of disingenuous

wile. Her voice is expressive and the tone beautiful, though at times I’d have liked a fuller sound: the final note of ‘Kl‰nge der Heimat’ was a bit

snatched – which was disappointing following such a charismatic rendition, though the tempo felt a bit ponderous.

Peter Davoren’s Alfred had a nice golden sound and despite his unintelligible Italian accent – his text is peppered with Italian – he successfully avoided

the ‘Italian tenor’ stereotype. Alfred can be a bit wearing, but Davoren was more puppyish than preening; his willingness to suffer and spare his lover’s

blushes won our sympathy, all the more so when he appeared from the cells in Act 3, trussed like a chicken, reduced to hopping feebly about in

disorientated bewilderment.

Gavan Ring was excellent as a suave Falke, his baritone supple and smooth. Falke’s ‘Br¸derlein, Br¸derlein und Schwesterlein’ can be played quite

hauntingly, but here his paean to brotherhood was so persuasive that the partyers instantly stripped to their underwear, fulfilling Falke’s observation

that ‘pairs have formed, that many hearts in love are bound’ – as the macho waiters deftly swept up the discarded fineries.

I enjoyed Samantha Price’s Orlofsky: her mezzo is vibrant and assured, and she was the perfect party host – hospitable and indefatigable. Joanna Marie

Skillett was a characterful Ida and as Dr Blind Robert Burt bluffed and puffed through his unmusical monotones.

Susanna Hurrell (Rosalinde) and Samantha Price (Prince Orlofsky)

Susanna Hurrell (Rosalinde) and Samantha Price (Prince Orlofsky)

Ian Jervis was a curmudgeonly Frosch whose Act Three monologue spiked several Conservative MPs – Brexiteers, Remainer and Regrexiteers alike – prompting

some belly laughs in the prison gloom.

Guiding the show, conductor John Rigby exhibited a no-nonsense approach borne of his experience in musical theatre, and the shirt-sleeved City of London

Sinfonia served him well. Rigby’s West End credits include The King and I and Sinatra at the London Palladium, Marguerite at the

Theatre Royal, Haymarket, Les MisÈrables at the Palace Theatre, The Phantom of the Opera at Her Majesty’s Theatre, and The Producers at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane; and this was a wise conducting appointment for the score danced to a tight beat, while the

woodwind players were allowed some slack for their expressive rubatos. The overture took off like a shot and the momentum did not flag – though I felt some

empathy for the second fiddles and violas whose right elbows must have been drooping by the end of the sweltering evening – all that oom-cha-cha waltzing!

Perhaps some of the orchestral details and tonal variety didn’t come across – more might have been made of the orchestration of the Czardas, all flutes,

clarinets, and tambourines, which so differs from the prevailing string-dominated idiom – but the Straussian spirit was heeded.

Die Fledermaus

is essentially an ensemble piece with the emphasis on dramatic interplay as much as on vocal sparkle. Here, the waltzes swirled, the corks popped

and the pleasure-seekers rocked, as Lloyd-Jones and his team raised their glasses to this Dom Perignon of operettas.

Claire Seymour

Johann Strauss II: Die Fledermaus

Gabriel von Eisenstein – Ben Johnson, Rosalinde – Susanna Hurrell, Adele – Jennifer France, Ida – Joanna Marie Skillett; Alfred – Peter Davoren, Falke –

Gavan Ring, Dr Blind – Robert Burt, Frank –John Lofthouse, Prince Orlofsky – Samantha Price, Frosch – Ian

Jervis; Director – Martin Lloyd-Evans, Conductor – John Rigby, Designer – takis, Lighting Designer – Howard Hudson, Choreographer – Adam Scown, Chorus

Master – Harry Ogg, City of London Sinfonia, Chorus of Opera Holland Park.

Opera Holland Park, Kensington, London; Tuesday 19th July 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Champagne.jpg

image_description=Die Fledermaus, Opera Holland Park

product=yes

product_title=Die Fledermaus, Opera Holland Park

product_by=A review by Claire Seymour

product_id=Above: The champagne aria