A Midsummer Night’s Dream

is a felicitous choice for this year’s Aldeburgh Festival as it was the

opera with which Britten opened Snape Maltings Concert Hall fifty years ago

in 1967. Since then, the Maltings have burned to the ground, been reborn

(in 1970), and undergone significant development while always remaining

true to Britten’s vision and ethos. But, the concert hall itself, wide and

lacking wings, is not the most accommodating space for opera. Jones makes a

virtue of a problem, and dispenses with the usual trappings of theatre –

set, props (bar a pendulous swing centre-stage), using digital projection,

colour, light and movement to conjure an eerie hinterland.

The deep-blue back-screen twitches with a filigree of cobwebs, leaves as

fragile as butterfly wings, and trembling droplets of dew on dandelion

threads; images which echo the woods and waterfalls of John Piper’s

original designs. It’s as if we are wandering through the botanical

woodcuts of an Elizabethan herbal. And, with the night come bees and

beetles, spiders and owls, busily spiralling or coolly perching. But, there

are other visual resonances too. Velvety petals unfold and sticky stamens

twitch with the sensuousness of Georgia O’Keeffe’s lilies; moreover, the

exquisite detail recalls Richard Dadd’s The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke with its mesmerising vision of

the microscopic secrets of the world sprites and spirits.

Spot-lit silhouettes mirror their subjects but, desynchronised movements

also teasingly elaborate and challenge. The foliage seems to stretch out

and enfold; figures drapes themselves in the leafy shadows. The disruptions

of scale and distortion of perspective blur boundaries between the real and

the fantastic. The overall effect is disorientating but mesmerising.

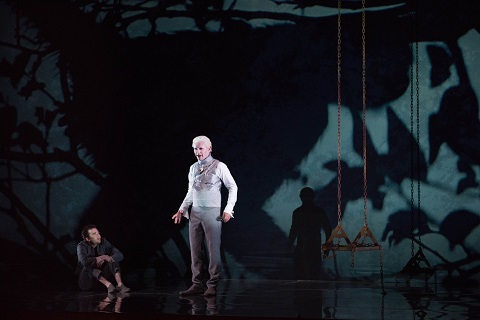

At the heart of this vision-scape is Iestyn Davies’ malevolent Oberon – a

silvery portrait of, paradoxically, stillness and wrath. Like an alchemist

skilled in secret arts, Oberon’s darkness is distilled in syrup of

love-in-idleness, drops of which splash and infuse the sleepers’ dreams.

This medic can both cure and harm, as the winding sinuousness of the snake

who ‘throws her enammel’d skin’ reminds us. Davies was initially a cruel

Oberon: the low range of his penetratingly precise countertenor resonated

with menace. But, disembodied against his silhouette, his voice had a

disturbing beauty which spoke of the fairy monarch’s passion for his

estranged Queen. Touched by pity for the doting Tytania, Oberon removes the

‘hateful imperfection’ from her eyes, and as the vocal line fell once more

in register, Davies’ imbued it with an expressive warmth, blending movingly

with the tone-clusters in the low cellos and double basses.

Jack Lansbury (Puck) and Iestyn Davies (Oberon). Photo credit: Hugo Glendinning.

Jack Lansbury (Puck) and Iestyn Davies (Oberon). Photo credit: Hugo Glendinning.

Like Prospero taunting Ariel, this Oberon dangles Puck on an invisible

magnetic cord, spitefully tugging, pulling and twisting his goblin servant

in meanness and rage. The acrobatic grace and physical responsiveness of

Jack Lansbury’s lithe Puck was breath-taking; this Puck was mischievous but

not malign, and his punishment – underscored by a vicious timpani roll and

stabs of gong, cymbal and xylophone – emphasised the heartlessness of the

imperious Oberon.

Sophie Bevan (Tytania) and the Fairies. Photo credit: Hugo Glendinning.

Sophie Bevan (Tytania) and the Fairies. Photo credit: Hugo Glendinning.

Jones’ fairy world is blanched of colour, drenched in silver light.

School-boy fairies in shorts, knee-high socks and top-hats, protect their

eyes with dark glasses, as they stand guard over the reposing Fairy Queen,

the disputed Indian boy a tiny black-frocked figure in their midst. The

boys of Chelmsford Cathedral choir sang their lilting lullabies and

heralded their mistress’s beloved Bottom with purity, sweetness and

strength. But, there was golden warmth, too, in the form of Sophie Bevan’s

gloriously luscious soprano which had the density of bullion and the

diamond-brightness of the stars. At the close of Act 1 when Tytania calls

her elfin brood around her and reflects on the ‘clamorous owl’ that wonders

at the ‘quaint spirits’, Bevan nailed the top C# with thrilling power,

running down the octave with the elegance of Oberon’s melismatic charms.

The besotted Tytania’s infatuation with the beastly Bottom was entirely

credible: ‘Oh how I love thee! How I dote on thee!’ was radiantly

soporific, burningly with monomaniacal passion. It was hard to know if such

love was ridiculous or sublime.

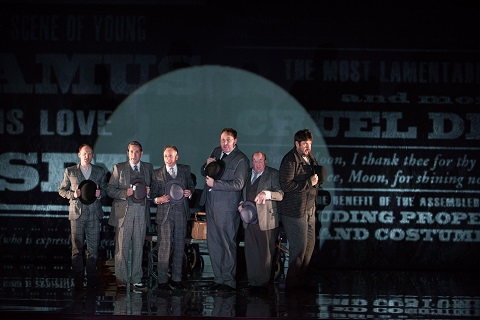

Jones’ projections in the mechanicals’ scenes – a mosaic of cogs and

buttons – alluded to their trades, and the rehearsals for their play were

fittingly downbeat: these were a pretty dull and maladroit bunch of

would-be thespians, lacking interest and energy and needing the bicycling

Bottom’s coercive enthusiasm to stir them to creative endeavour. Matthew

Rose was no buffoon, though his sonorous bass conveyed the weaver’s sense

of his own stature and worth; even when adorned with ass’s horn and tail,

and stripped to stockings and suspenders, Bottom was more a figure of

pathos than of ridicule, as he executed a nifty Morris dance to the

fairies’ percussive accompaniment.

The Mechanicals. Photo credit: Hugo Glendinning.

The Mechanicals. Photo credit: Hugo Glendinning.

Act 3’s play-within-a-play is always in danger of being more ‘lamentable’

than comic, but Jones avoided too much hamming and dealt deftly with the

stage ‘business’ of moonshine, walls and lions: the rustics chimed

tunefully as a barbershop sextet, and though Snout (Nicholas Sharratt) and

Starveling (Simon Butteriss) looked as if they might break out into ‘Brush

Up Your Shakespeare’ they confined themselves to a quick toe-spin. Lawrence

Wiliford’s Flute avoided too many echoes of Peter Pears’ original Joan

Sutherland send-up, and Rose did not make a meal of Pyramus’ demise, adding

only one extra “die”, to the five expirations indicated in the libretto!

When, following a rehearsal, the mechanicals leave one of their carts

behind in the wood, it provides a bed first for Lysander, then Tytania and

finally for Bottom himself, thereby neatly linking three worlds. Awakening,

Bottom puzzles over his experiences: it is ‘past the wit of man to say what

dream it was’. Rose’s rendition of ‘Bottom’s Dream’ was a beautifully

expressive climax to the opera, his bass falling with a beguiling sway

through the descending thirds. Here it became clear that the weaver’s

synaesthesic confusion – ‘The eye of man hath not heard, the ear of man

have not seen’ – had been so perfectly embodied by Jones’ design.

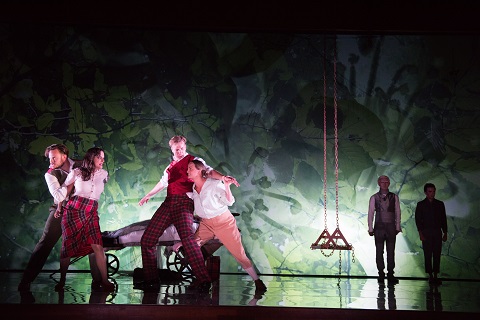

In contrast to the albino fairies, the mortal lovers’ arrival is

accompanied by an injection of crimson red and verdant greens, the rustling

leaves shifting with sensuousness, and the striking palette complementing

the richness of the blended quartet of voices. The opera’s set pieces

belong to the Fairies and to Bottom though, and it was harder for the four

mortals to project the text (there were no surtitles), though there was a

good attempt to individualise and distinguish between the quartet of duped

beloveds.

Nick Pritchard (Lysander), Clare Presland (Hermia), George Humphreys (Demetrius), Eleanor Dennis (Helena). Photo credit: Hugo Glendinning.

Nick Pritchard (Lysander), Clare Presland (Hermia), George Humphreys (Demetrius), Eleanor Dennis (Helena). Photo credit: Hugo Glendinning.

Nick Pritchard’s Lysander was earnest and his tenor had an occasional grain

which deepened the characterisation, while George Humphreys’s tall,

tartan-trousered Demetrius was forthright, sonorous and indignant. Clare

Presland’s Hermia flashed with fire during the exchanged of insults with

Eleanor Dennis’s Helena, the latter’s breeches emphasising her height

advantage over the ‘dwarfish’ Hermia, and the creamy richness of her

soprano winning our sympathy for the maiden spurned by Demetrius: ‘I am

sick when I do look on thee’. There were some welcome dashes of humour,

too, to lighten the belligerent resentment of the fairies’ feud, as when

Lysander’s struggles to lift his beloved Hermia’s suitcase, as they made

their escape from the oppressive Egeus, indicated that this eloper did not

intend to travel light.

The shift to the courtly elegance of the final act is always something of a

jolt; as if not just the characters but we too are awakening from the

compelling charms of the subconscious. Jones chooses to emphasise the

schism by presenting a stunning sunrise of complementary indigos and

oranges which brought to mind the vivid palette of Turner’s Dawn After the Wreck. White grid lines dissect the projection,

emphasising the artifice of the image – a fitting complement for Theseus’s

discourse on mimesis and myth. Clive Bayley was a stentorian monarch and

Leah-Marian Jones his feisty consort.

Conductor Ryan Wigglesworth gave the Aldeburgh Festival Orchestra a pretty

free rein, which allowed us to enjoy Britten’s orchestral mastery: celeste

and percussion were an uncanny presence during Oberon’s pronouncements, the

trumpet chirruped brightly during Puck’s escapades, the harps rocked with

tenderness as Tytania instructed her fairies to attend to Bottom’s every

need. This is a score I know well but there were still many places where my

ear was caught by a fresh detail or colour. The lethargic glissandi which

penetrate the score had the deep-breathed absorption of sleepy oblivion,

but the richness and urgency of Wigglesworth’s account did at times make it

difficult for the singers to get the text across.

But, leaving the Maltings, bathed in the serene glow of the full midsummer

moon, I felt that I had been truly bewitched.

Claire Seymour

Benjamin Britten: A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Oberon – Iestyn Davies, Tytania – Sophie Bevan, Puck – Jack Lansbury,

Theseus – Clive Bayley, Hippolyta – Leah-Marian Jones, Lysander – Nick

Pritchard, Demetrius – George Humphreys, Hermia -Clare Presland, Helena –

Eleanor Dennis, Bottom – Matthew Rose, Quince – Andrew Shore, Flute

-Lawrence Wiliford, Snug – Sion Goronwy, Snout – Nicholas Sharratt,

Starveling – Simon Butteriss, Cobweb – Elliot Harding-Smith, Peaseblossom –

Ewan Cacace/Angus Hampson, Mustardseed – Adam Warne, Moth – Noah Lucas,

Chorus of fairies (Willis Christie, Lorenzo Facchini, Angus Foster,

Nicholas Harding-Smith, Kevin Kurian, Charles Maloney-Charlton, Robert

Peters, Matthew Wadey; chorus master – James Davy).

Netia Jones – direction/design/projection, Ryan Wigglesworth – conductor,

Oliver Lamford -assistant director, Jenny Ogilvie – choreographer, Sam

Paterson – production manager, Joe Stathers-Tracey – video technical

manager, Katie Higgins & Madeleine Fry – costume supervisors, Aldeburgh

Festival Orchestra.

Snape Maltings Concert Hall, Friday 9th June 2017.

image= http://www.operatoday.com/Fairy%20silhouette.jpg

image_description=A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Snape Maltings, Aldeburgh Festival 2017

product=yes

product_title=A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Snape Maltings, Aldeburgh Festival 2017

product_by=A review by Claire Seymour

product_id=A fairy silhouette

Photo credit: Hugo Glendinning