There is a host of fine operas out there languishing more or less

unperformed (in some cases, quite unperformed). A few of them might even

qualify as ‘great’. Franz Schreker’s Die Gezeichneten, whatever

its proponents might claim, is certainly not one of those: not even close. Nor,

however, is it a piece that fails to merit the occasional outing. Whether it

merits the torrent of productions seemingly in store is rather less clear. For

what it is worth — and this is partly a matter of taste, or lack thereof

— there is not a single opera by Mozart, Haydn, or Gluck I should not

rather see before sitting through this again. That said, I was immensely

grateful not only for the opportunity afforded by the Bavarian State Opera not

only to see the opera staged, but to see and hear it performed and staged so

well — so much so, indeed, that the whole experience was enjoyable,

absorbing, very much more so, I think, than the intrinsic merits of the opera

might suggest.

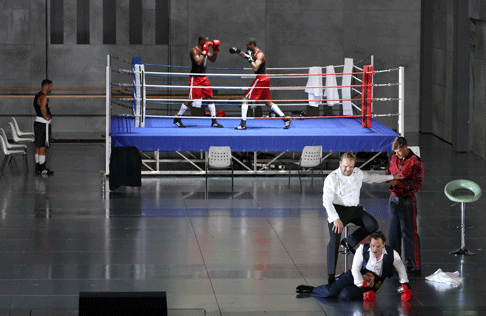

Tomasz Konieczny (Herzog Antoniotto Adorno), Christopher Maltman (Graf Andrea Vitellozzo Tamare), Statisterie der Bayerischen Staatsoper

Tomasz Konieczny (Herzog Antoniotto Adorno), Christopher Maltman (Graf Andrea Vitellozzo Tamare), Statisterie der Bayerischen Staatsoper

That might sound odd, but it is not really so very odd — at least not

necessarily. A peculiarity, indeed a fascination, to the opera is that almost

every charge one might lay at its door might conceivably meet with the

rejoinder: ‘that is the point’. It depends whose point, really: it

is less often the point if we focus narrowly on ‘intention’, but

why should we? Krzysztof Warlikowski’s production seems to nod to this

thorny question by interpolating, immediately after the interval, before the

third of the three acts, Schreker’s own character sketch of 1921, in

which he presents — even, to an extent, ‘reclaims’, as we

might say — accusations thrown at him and his art. It is, we may be

reasonably sure, intended ironically or, perhaps better, with understandably

vicious sarcasm, having been constructed from criticisms he had received:

I am an Impressionist, Expressionist, Internationalist, Futurist, a musical

purveyor of verismo; Jewish, and rose through the power of Jewishness;

Christian and was ‘made’ by a Catholic clique under the patronage

of a Viennese arch-Catholic countess.I am a sound artist, sound fantasist, sound magician, sound aesthete, and

have no trace of melody (other than so-called short-breathed empty phrases,

newly known as Melodielein). I am a melodist of the purest blood, as a

harmonist however, anaemic, but perversely in spite of this a full-blooded

musician! I am (unfortunately) an erotomaniac and work balefully upon the

German public (eroticism is obviously my innermost contrivance, despite

Figaro, Don Giovanni, Carmen,

Tannhäuser, Tristan, Walküre,

Salome, Elektra, Rosenkavalier, and so on). …

The rest, in which he continues, to explain that he is not of the true

modernistic ‘left’ (Schoenberg and Debussy), owes something to

Verdi, Puccini, Halévy, Meyerbeer, et al, and so on, may be

read here. (It is

well worth doing so, if you have the German.) It made for a powerful moment, or

rather few moments, in the theatre, not least since Warlikowski has it read by

the tragic, ugly hero-artist (the libretto was originally intended for

Zemlinsky), who thus becomes at least in part an explicit realisation of

Schreker’s plight. The problem, however, remains that, insofar

as we may dissociate criticism of Schreker from anti-Semitism — perhaps

it is impossible historically, but it need not be so now — many of the

criticisms levelled tend actually to be born out; either that or the

comparisons (Figaro, Tristan, etc.!) are rather embarrassing,

doing neither composer nor opera any favours at all.

Catherine Naglestad (Carlotta Nardi), Opernballett der Bayerischen Staatsoper

Catherine Naglestad (Carlotta Nardi), Opernballett der Bayerischen Staatsoper

What we have, then, is an evening in the theatre in which that problem is,

if not worked out, at least explored. The slipperiness of artistic creation and

agency is embodied in Alviano Salvago. Is he a good artist or a con artist?

There are many other possibilities; we do not end up necessarily falling short

of Mozart and Wagner because we are not trying. Salvago has created a garden of

delights, an island park of Elysium, which he wishes to give to the people of

Genoa. Is the suspicion of its establishment justified? In part, perhaps. Dark

things clearly go on there. Are they the creator’s doing? Not

intentionally, but they can be readily understood, made out to be, especially

by other, more attractive noblemen who wish to be able to pursue something far

more dastardly, indeed truly shocking — such as to leave our

aesthetic-moralistic sniping at Schreker-Salvago look at best misguided. Do we

really want to be the ones to say ‘yes, I’m sorry, your music is

overblown, verging on the formless, an illustration or at least a piece of

evidence, moreover, that Schoenberg was right: once a certain point of

chromaticism has been reached, there really is nowhere else to go other than

somewhere you would not…’, and so on? Of course we do not,

especially when we know with whom we are allying ourselves, especially when we

know how the crowd may be swayed — either by Salvago or by his opponents.

On the other hand, Goebbels is not the only option: there is Schoenberg too;

there is Moses und Aron, where we can see and hear these antinomies,

or better dialectics, actually treated with the seriousness they deserve.

Give ourselves a third hand, though, or, Blair forbid, a ‘third

way’, and perhaps we may wish to tarry. It is not as bad as Korngold,

say. There is genuine fascination in the harmonic and instrumental colour:

evidence of the most extraordinary ear. Alas, there is such an utter lack of

variety that it all sounds more or less the same. One may like the sound; I

might, for a few minutes. But for three acts? Three acts, that is, intruded

upon only by a strange vulgarity in the third: dramatically effective, to a

certain extent, as a suggestion of crowd dynamics, yet ultimately incongruous

and, more to the point, unconvincing. The lack of ‘traditional’

melodic invention is not the end of the world in itself, but let us not

convince ourselves that this is replaced by the still well nigh incredible

perpetual self-transformation of Erwartung. Nor is the lack of musical

characterisation necessarily fatal, although it is clearly a flaw, for this is

not Fidelio, in which characterisation is simply not the point.

Returns, however magnificent they sound in themselves, diminish all the time,

without ever being replaced by something which, in that old Romantic way, we

might consider to be true inspiration. Contrivance is all very well; who cares,

ultimately, if the result is good. But is it?

Warlikowski proves himself, unsurprisingly, a dab hand at the erotomaniac

side of things. The burlesque dance performed before the angry Schreker-Salvago

is not the half of it, although it is perhaps the most memorable side. He shows

also, quite unsparingly, how evil one side of the accusers is: that is, the

party of Vitelozzo Tamare. Rich, unscrupulous, deceiving, plausible, violent:

it is they who do the real harm, who have kidnapped and abused Ginevra Scotti,

whilst framing the poor Salvago. How many other productions manage to

incorporate a boxing training session into proceedings, as if to underscore the

lavish obscenity of the violence? The humanity of the genuine artist, Carlotta,

is underscored equally well, not least given an exemplary, heartfelt

performance from Catherine Naglestad. She looks for the soul and perhaps she

finds it: or perhaps, given her fate, she realises there is none at all, and is

better off out of the game entirely. In that, encasing herself, she becomes an

installation, perhaps an artwork of her own. The raging rodent crowd —

more than a nod to Hans Neuenfels’s Lohengrin — would

neither understand nor care. Salvago does though — we think.

The Bavarian State Orchestra under Ingo Metzmacher played with such glorious

golden tone that it might have been the Vienna Philharmonic in Strauss —

other, that is, than the score itself not having Strauss’s sense of

drama, of direction, of characterisation, and so on, and so on. There was no

sense of hurrying, which may or may not have been an unalloyed advantage. I

think it was pretty much an advantage, for one certainly gained the impression

of the score being permitted to speak for itself, even if to be hoist by its

own petard. John Daszak gave a deeply moving account — like so many of

the performances, seemingly moving beyond the limitations of the work

‘itself’ — of the central role. Christopher Maltman proved

diabolically irresistible as his wicked opponent in love, art, and so much

more; there was more than a hint of an ultra-decadent Don Giovanni here

(definitely without the idealism — or Idealism). Tomasz Konieczny gave a

magnificently forthright performance as Duke Adorno: duly ambiguous as to whose

side he was on, if any, never anything but fully committed, though, in vocal

terms. The doubling of his part with that of the Capitaneo di giustizia —

gleefully ripping off his mask to confirm what we suspected — only

heightened the troubling implications. The huge cast did not, so far as I can

recall, have a single weak link to it; this, and the equally fine choral

contribution showed just what an opera house and company can achieve. The

extraordinarily self-reflexive quality of the evening and its aftermath will, I

suspect, continue to intrigue. The Vorspiel zu einer Drama, the

concert version of the opening Prelude, both says it all — and yet, in

another way, says none of that.

Mark Berry

Cast and production information:

Duke Antoniotto Adorno/Capitaneo di giustizia: Tomasz Konieczny; Count

Andrae Vitelozzo Tamare: Christopher Maltman; Lodovici Nardi: Alastair Miles;

Carlotta Nardi: Catherine Nagelstad; Alviano Salvago: John Daszak; Guidobald

Usodimare: Matthew Grills; Menaldo Negroni: Kevin Conners; Michelotto Cibo:

Sean Michael Plumb; Gonsalvo Fieschi: Andrea Borghini; Julian Pinelli: Peter

Lobert; Paolo Calvi: Andreas Wolf; Ginevra Scotti: Paula Iancic; Martuccia:

Heike Grötzinger; Pietro: Dean Power; Youth: Galeano Salas;

Friend/Servant/Giant Citizen: Milan Siljanov; Girl: Selene Zanetti; Senators:

Ulrich Reß, Christian Rieger, Kristof Klorek; Little Boy: Soloist from

the Tölz Boys’ Choir; Servant: Niamh O’Sullivan; Father: Yo

Chan Ahn; Mother — Eleanor Barnard; Citizens: Harald Thum, Thomas

Briesemeister, Klaus Basten, Burkhard Kosche, Tobias Neumann, Sebastian Schmid.

Director: Krzysztof Warlikowski; Designs: Malgorzata Szcz??niak; Lighting:

Felice Ross; Choreography: Claude Bardouil; Video: Denis Guéguin;

Dramaturgy: Miron Hakenbeck: Children’s Chorus (chorus master: Stellario

Fagone) and Chorus (chorus master: Sören Eckhoff) of the Bavarian State

Opera/Bavarian State Orchestra/Ingo Metzmacher (conductor). Nationaltheater,

Munich, Tuesday 4 July 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/5M1A0891.png

image_description=JOHN DASZAK (ALVIANO SALVAGO) [Photo © Wilfried Hˆsl]

product=yes

product_title=Franz Schreker: Die Gezeichneten

product_by=A review by Mark Berry

product_id=Above: John Daszak as Alviano Salvago

Photos © Wilfried Hˆsl