Speak to the audience in Munich’s Prinzregententheater it certainly seemed

to – rightly or wrongly. I could only wish that both the work and those of

us in the audience who thought otherwise had not been treated with such

condescension. That may sound reactionary. Perhaps indeed it is; perhaps

all that matters is that those many people who enjoyed such an

‘entertainment’, to use a properly eighteenth-century word, did indeed

enjoy it. Perhaps. Let me, however, try to explain why I found this, much

fine singing notwithstanding, a somewhat dispiriting experience.

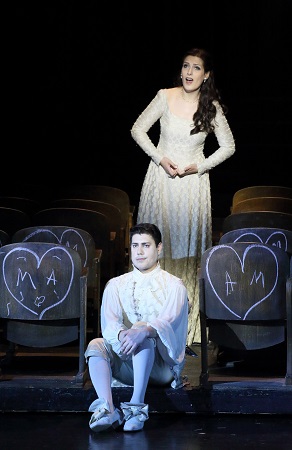

Tara Erraught (Alcina) and David Portillo (Pasquale). Photo credit: Wilfried Hˆsl.

Tara Erraught (Alcina) and David Portillo (Pasquale). Photo credit: Wilfried Hˆsl.

No one, I think, would claim Nunziata Porta to be one of opera’s greatest

librettists; this is not a Da Ponte, a Wagner, or a Hofmannsthal. Nor

indeed a Metastasio. However, his libretto here is, by the same token,

likely to be underestimated, precisely because of where his talents lay.

His principal occupation at Esterh·za was to adapt texts, including

provision of insertion arias. (If you do not know any of Haydn’s, for

obvious reasons far less widely known than Mozart’s, then they are well

worth discovering.) And that is what he did here, on a larger scale, with Orlando Paladino, helping Haydn create a rather extraordinary

work, a dramma eroicomico after Ariosto. Its skill lies not just in

parodying Ariosto, indeed not primarily in that at all, but in permitting

Haydn to do so and indeed to parody much else besides: often wryly, subtly,

sometimes more overtly – here, at least in one particular instance, in

Pasquale’s ‘Ecco spanio’, Ranisch worked highly successfully with libretto and music. Otherwise, I am afraid, far too little of that came

through – which was surely something a skilled production might have seen

as its purpose or at least a good part of it.

Dovlet Nurgeldiyev (Medoro) and Adela Zaharia (Angelica). Photo credit: Wilfried Hˆsl.

Dovlet Nurgeldiyev (Medoro) and Adela Zaharia (Angelica). Photo credit: Wilfried Hˆsl.

Yes, one might respond, but what if an audience does not understand the

conventions of late-ish eighteenth-century opera seria? Do we not

need to find a way of leading many listeners in? We probably do, or at

least in certain circumstances it might be a good idea. (Heaven forfend we

might actually expect some work from an audience; nevertheless, if I do not

read Russian, I do not claim the problem to lie in Pushkin.) A similar

problem, after all, seems often to be experienced with CosÏ fan tutte, which very few seem to understand – or, more to

the point, take the trouble to try to understand. (Sometimes it is not ‘all

about you’.) By all means, though, lead us in, show us what the opera is or

might be about. Ranisch, however, seemed to have no interest whatsoever in

doing so. Not unlike Christof Loy in his unforgivable

Salzburg Frau ohne Schatten

, albeit less aggressively, the message seemed to be: ‘forget about this; I

do not like this story very much, so here is another one’.

Alas, Ranisch’s new story seems to me only slightly less banal than Loy’s.

For all the filmic creativity – undeniable in its way, if hardly

groundbreaking – what we have ultimately is a new, less than captivating,

tale of a married couple who own a cinema. One of them is at least partly

gay and fantasises about the handsome Rodomonte (or perhaps the

actor/singer who plays him). When technical problems cause an explosion in

the cinema, he takes the opportunity to wander into the scenes on screen to

learn a bit more about himself. A huge amount of silly running around,

pulling faces, and so on, detracts entirely from the opera and at best has

one wonder what on earth is going on. Now there may well have been a way,

even within this particular metatheatrical framework, to engage with the

work, to do more of what I have suggested it might. It really does not

seem, though, to happen here. A pair of actors, ‘Gabi and Heiko Herz’, seem

the most honoured here. Ironically, however, the banality of their story,

the striking Cinema Paradiso homage in Falko Herold’s designs

notwithstanding, throws one’s attention back towards the singing, if only

out of desperation. We end up with another tired old clichÈ, that

eighteenth-century opera other than Mozart’s is ‘really’ only about

singing. Orlando Paladino and Haydn thus found themselves doubly

damned.

Gabi and Heiko Herz. Photo credit: Wilfried Hˆsl.

Gabi and Heiko Herz. Photo credit: Wilfried Hˆsl.

Such might have been less the case, had it not been for Ivor Bolton’s

rigid, often hard-driven conducting, which paid little attention, if any,

to Haydn’s harmonic rhythm, living if indeed it lived at all only in the

moment – perhaps not so ill-suited a complement to the production. The

playing of the Munich Chamber Orchestra was in itself excellent, however.

One longed for it to be let off its leash, though, not least for the

strings to be permitted greater vibrato. There seemed little doubt that

they longed for that too. Nevertheless theirs was fine playing, woodwind

solos especially joyous. For the real thing, though, turn on record to

Antal Dor·ti – or even, should this be your real thing and you can

somehow stand the weird perversities, to Nikolaus Harnoncourt. Those

perversities may eclipse formal understanding, or at least the

communication thereof, but at least they seem less generated on auto-pilot.

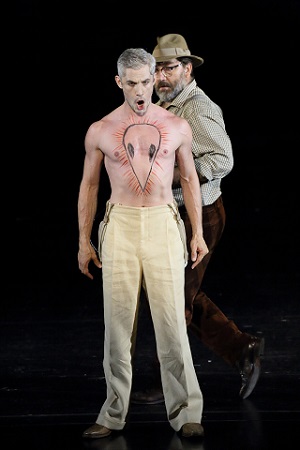

Edwin Crossley-Mercer (Rodomonte) and Heiko Herz. Photo credit: Wilfried Hˆsl.

Edwin Crossley-Mercer (Rodomonte) and Heiko Herz. Photo credit: Wilfried Hˆsl.

It was, then, to recapitulate – more of such formal understanding from the

conductor, please! – from the singers that considerable pleasure and

insight was to be gleaned. Mathias Vidal as Orlando trod a fine line,

sensitively and stylishly, between bravado and acknowledged weakness. So

indeed did all the male singers; such, not without a pinch of what we might

anachronistically think feminism, is indeed the point. Edwin

Crossley-Mercer’s diction was not always clear as it might have been,

especially in so small a theatre; however, his dark tone proved full of

allure – increasingly compromised allure. Dovlet Nurgeldiyev, for me one of

the true discoveries of the evening, offered almost heartbreaking tonal

beauty, whilst also making as much of the words as the production

permitted. Likewise his intended, Adela Zaharia. David Portillo, a

supremely versatile singer, finely attuned both to line and style,

impressed greatly as Pasquale; his aforementioned aria was probably the

highpoint of the entire evening. Elena Sancho Pereg, as Eurilla, proved

very much his equal: a fine foil, but also a spirited character in her own

right. Tara Erraught’s rich mezzo Alcina left one longing for more. It was

she, above all, who brought moments of true drama to proceedings. Perhaps

she, instead, should have been directing and/or conducting.

Mark Berry

Haydn: Orlando Paladino Hob.XXVIII:11

Angelica: Adela Zaharia; Rodomonte: Edwin Crossley-Mercer; Orlando: Mathias

Vidal; Medoro: Dovlet Nurgeldiyev; Licone: Guy de Mey; Eurilla: Elena

Sancho Pereg; Pasquale: David Portillo; Alcina: Tara Erraught; Caronte:

FranÁois Lis; Gabi and Heiko Herz: Heiko Pinkowski, Gabi Herz. Director:

Axel Ranisch; Conductor: Ivor Bolton; Designs: Falko Herold; Choreography:

Magdalena Padrosa Celada; Lighting: Michael Bauer; Dramaturgy: Rainer

Karlitschek. Statisterie and Opera Ballet of the Bavarian State Opera.

Prinzregententheater, Munich, Sunday 29 July 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Alcina%20and%20Angelica.jpg

image_description=Haydn’sOrlando Paladino: Munich Opera Festival

product=yes

product_title= Haydn’s Orlando Paladino: Munich Opera Festival

product_by=A review by Mark Berry

product_id= Above: Tara Erraught (Alcina) and Adela Zaharia (Angelica)

Photo credit: Wilfried Hˆsl