American author Gail Carson Levine’s award-winning fantasy-novelElla Enchanted was published in 1997, and as recently as 2015 Walt Disney Pictures revisited the romantic fantasy, producing a

live-action re-imagining of the original 1950 animated film. Both a

Filipino pop group that rose to prominence in the 1970s, and an American

glam rock band formed in Pennsylvania in 1982 and which had a series of

multi-platinum albums and hit singles, chose to call themselves after the

undervalued skivvy.

Postage stamp issued in West Berlin in 1965 which depicts Cinderella leaving behind her golden slipper

Postage stamp issued in West Berlin in 1965 which depicts Cinderella leaving behind her golden slipper

According to some sources, there are over 1500 adaptations of the Cinderella story, the earliest version of which is usually

considered to be the Greek philosopher Strabo’s account of a Greek slave

girl who marries the Egyptian King. Made popular by Charles Perrault in Histoires ou contes du temps passÈ in 1697 and subsequently by the

Brothers Grimm in their ‘darker’ version of the folk tale (in

‘Aschenputtel’, published in the collected Fairy Tales of 1812,

the step-sisters are so grotesquely greedy that they are willing to hack

bits off their feet to force them into the slipper!), Cinders’ true virtue

has earned its just reward in countless pantomimes and plays, ballets and

films, musicals and novels.

The earliest known British pantomime based on Cinderella was first

performed at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in London in 1904, and now Baron

Hard-Up, the Ugly Sisters and Buttons are perennial Christmas favourites.

In 1957 Rodgers and Hammerstein gave us a television musical with Julie

Andrews in the eponymous role. Prokofiev put the glass slipper en pointe, though Tchaikovsky almost got there first, writing to

his brother Modest in October 1870, ‘Just imagine, that I’ve undertaken to

write the music for a ballet Cinderella, and that this vast

four-act score must be ready by the middle of December!’, though this

commission for his first ballet remained unfulfilled. Ferdinand Langer

(1878), Johann Strauss II (1901) and Frank Martin (1941) have all taken

Cinders to a ballet-ball; and, Christopher Wheeldon, who in 2013 added

puppetry (by Basil Twist) to Prokofiev’s score, will choreograph a new

production of Cinderella, co-produced by English National Ballet

and the Royal Albert Hall where it will be performed in the round in June

next year, which is being billed as ‘the ballet spectacular of 2019’.

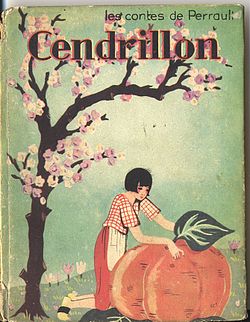

Front cover of a 1930 French picture book edition of Cinderella

Front cover of a 1930 French picture book edition of Cinderella

Cinemas have offered sugary sweet adaptations of the young girl’s journey

from misery to matrimony, such as The Slipper and the Rose

(starring Richard Chamberlain and Gemma Craven, 1976) and Ever After (1998, featuring Drew Barrymore). And, of course, in

the opera house numerous composers have literally given Cinderella a

‘voice’, from Jean-Louis Laruette and Louis Anseaume (1759) to Stefano

Pavesi (1814), from Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari (1900) to Gustav Holst (1901),

from Peter Maxwell Davies (1979) to

Alma Deutscher

(2016), among others.

Of course, the operatic versions of Goodness Triumphant by Giacomo Rossini

(La Cenerentola, 1817) and Massenet (Cendrillon, 1894-6)

are the best-known. But, in the early nineteenth century it was not Rossini

whose Cinderella was most celebrated but that of the Franco-Maltese Nicolas

– or NicolÚ, as he called himself – Isouard, whose three-act comic opera, Cendrillon, to a libretto by Charles-Guillaume Etienne

after Charles Perrault, was premiered in the Salle Feydeau at the

OpÈra-Comique on 22nd February 1810. And, it is this opÈra-fÈerie by Isouard, who died two hundred years ago, that Bampton Classical Opera –

celebrating their twenty-fifth year – have selected for their 2018

production and which, following performances earlier this summer at Bampton

and Westonbirt, can now be enjoyed at

St John’s Smith Square on 18th September

.

Nicolas Isouard

Nicolas Isouard

So, who was NicolÚ Isouard, this composer of more than 40 operas, whose

bust graces the pediments of the Palais Garnier in Paris? The son of a

Marseille merchant, Isouard was born in Valletta on 18th May

1773 (according to Grove; some sources suggest 6th December

1775). His early education, which included mathematics, Latin and music,

took place in Paris at the Pensionnat Berthaud, a preparatory school for

the Engineers and Artillery, but the Revolution forced him to flee back to

Malta in 1789 where his father found him a position in a merchant’s office.

He continued his musical studies – composition with Michel-Ange Vella and

counterpoint with Francesco Azzopardi; when his work took him to Palermo,

he took harmony lessons with Giuseppe Amendola; later, in Naples, he

completed composition studies with Nicola Sala and received practical

advice from Guglielmi.

Isouard made his debut as an opera composer with L’avviso ai maritati in June 1794, which was successfully received

in Florence and later given in Lisbon, Dresden and Madrid. Back home, not

all spoke favourably of Isouard, some questioning his masonic affiliations.

In April 1794, the Maltese Inquisition was told that the composer was ‘a

young man who leads a sinful life, frequenting loose women, and boasting

about it. He ridicules and despises the sacrifice of the Mass […] those

acquainted with him consider him a libertine’, but despite such

condemnation, in 1795, on the death of Vincenzo Anfossi, Isouard was

appointed organist to the Order of St John of Jerusalem in Valetta, later

becoming maestro di cappella there. He settled in Malta, composing serious

and comic operas for the Maltese theatre.

[1]

The French invasion of the island in June saw him become secretary to the

Governor of the French garrison, Vaubois, and following the French

submission to the British, Isouard, perhaps fearful of charges of

collaboration, returned with the latter to Paris in 1799. His first

Parisian opÈra comique, Le petit page, composed

in collaboration with Rodolphe Kreutzer who acted as Isouard’s manager and

patron, was given in the ThȂtre Feydeau in February 1800. Friendship with

the librettist F.-B. Hoffman led to the sharpening of his dramatic insight,

and his first major success came with Michel-Ange (1802).

On 5th August 1802, Isouard co-founded – with Luigi Cherubini,

Etienne-Nicolas MÈhul, Rodolphe Kreutzer, Adrien BoÔeldieu and Pierre Rode

– Le magasin de musique dirigÈ, a publishing venture which

formally opened in December that year, in premises at 268 rue de la Loi in Paris (in 1805-6 the street number and name were

altered to 76 rue de Richelieu). The company was designed to spare

composers – who in the late-eighteenth century habitually self-published

their works and sold them personally or through music shops – from

financial risk and time-consuming business matters, and to ensure that they

received increased publicity and profit. Each of the six composers was

contracted to furnish at least one opera or 50 pages of music each year,

and each was entitled to the proceeds from the sale of his own works and to

a share in the profits of the firm’s publications of works, mainly

instrumental compositions, by various non-associated contemporary composers

who were popular in Paris at the time.

Nicolas Isouard (drawing by Julien, Pierre Durcarme lithography, circa 1830, published by Blaizot, Universal Gallery, Place VendÙme, Paris)

Nicolas Isouard (drawing by Julien, Pierre Durcarme lithography, circa 1830, published by Blaizot, Universal Gallery, Place VendÙme, Paris)

In total more than 650 editions were published, from engraved plates,

including Viotti’s five violin concertos and, notably, the first edition in

full score of Le nozze di Figaro (1807-08). However, of the six

collaborators Isouard – who had the most extensive business experience

among the group – was alone in taking his prescribed obligations seriously:

the firm printed nine of his operas in full score, alongside Cherubini’sAnacrÈon, MÈhul’s Joseph and BoÔeldieu’s Ma tante Aurore. He left the firm in July 1807 and on 12 August

1811 the partnership was dissolved, J.-J. Frey acquiring the business,

manuscripts and 9679 engraved plates (of which Isouard’s contribution

accounted for 3,553 engraved pages, about 37% of the total).

[2]

In 1808, with Un jour ‡ Paris, Isouard began his long

collaboration with Etienne, who was the editor of the Journal des deux mondes. Two years later they had an unprecedented

success at the OpÈra-Comique in 1810 with the fairy-tale operaCendrillon, and further triumphs followed including Jeannot et Colin (1814) and Joconde (1814), the latter

establishing Isouard’s international reputation. He had little serious

competition among his fellow composers in Paris at this time, but with the

return of BoÔedlieu, from Russia, in 1811, a friendly rivalry was

initiated, one which became more acrimonious when both applied for

membership of the Institut de France (1817). BoÔeldieu’s success angered

Isouard who broke off relations with his former friend. Indeed, it has been

suggested that Isouard was driven to drink, debauchery and an early death

by his jealousy of BoÔeldieu!

[3]

Isouard, BoÔeldieu and MÈhul are often credited with having brought French opÈra comique to its final form. The genre is a significant marker

of changing taste in France in the early years of the nineteenth century.

While the French did share Napoleon’s liking for Italian opera and

aristocratic themes, opÈra comique

came to be strongly identified with the cultural appetites of the

post-revolutionary bourgeoisie who, after years of Revolutionary

turmoil and bloodshed, now longed for simple entertainments that would

amuse and bring joy. Characters were drawn from everyday life; plots

involved complicated deceptions and subterfuges; a pair of lovers was

unfailingly at the centre of the drama. The story was advanced by

spoken dialogue and the music was ‘uncomplicated’: melodious strophic

airs and romances, pictorial orchestrations, strongly defined musical

characterisation.

Though the genre is occasionally dismissed as light and trivial, both

Edward J. Dent and Donald Grout argue that it is in the op Èra-comique of the years from 1790 to 1815 that we should look for

the origins of mid-nineteenth-century Romantic grand opera.

Isouard certainly achieved great popularity at home and abroad during his

life-time. His operas were performed across Europe; Michel-Ange

was translated into five languages and L’intrigue aux fenÍtres

into seven. Born in Hanover in 1795, Sophie Augustine Leo, the writer of

the anonymous Erinnerungen aus Paris (Berlin, 1851), had travelled

to Paris with her elder sister Mme Valentin in 1817, and the year later

married the German banker August Leo, a prominent patron of the arts among

whose regular guests were many distinguished artists living in Paris at

this time. Writing of the ‘masterpieces’ that were being given at the

OpÈra-Comique during this period, Sophie remarked Isouard’s achievements:

‘His opera Jeannot et Colin, more especially his Rendezvous bourgeois, sparkled with life and animation; I doubt

whether a more amusing subject than the latter is to be found. Though I can

no longer remember enough of the detail to retell the story, I know that

the merriment of the spectators was endless and that the music had caught

the spirit of the text. L’intrigue aux fenÍtres followed, then Cendrillon and Joconde, and Isouard died, aged forty-one,

at the height of his development and in the ever increasing favor of his

public.’

[4]

She also noted that, ‘In 1818, i.e., shortly after my arrival in Paris,

connoisseurs were shocked by the deaths of Isouard and MÈhul’.

Frequently composers made adaptations and transcriptions of Isouard opera

airs. In 1810 Jan Ladislav Dussek published his “Variations No.4 in G major

on ‘Toto Carabo’ or ‘Il Ètoit un petit homme’ from the opera Cendrillon by NicolÚ Isouard arranged as a Rondo with Imitations”,

and one of Johann Nepomuk Hummel’s seven sets of variations on opera themes

took Cendrillon as its source.

Isoaurd’s fame and favour reached far afield. In his study of opera in

Philadelphia from 1800-30, Otto Albrecht demonstrates that Isouard’s work

was popular among the 258 different operas presented during in the city

during these thirty-one years. In October 1827 no fewer than three operas

by Isouard were performed: Cendrillon, ou Le petit soulier verd (first performed on 20th

October 1827) was preceded by Joconde, ou Les coureurs d’aventures

(1st October) and Les rendez-vous bourgeois (17 th October), while a year later on 18th October 1828

Isouard’s Lully et Quinault, ou Le dÈjeuner impossible was staged.

[5]

Further evidence of the dispersal of Isouard’s music in America can be

found in Charlotte le Pelletier’s ambitious Journal of Musick,

published in Baltimore in 1810. Pellier, a pianist and composer, had

arrived in Baltimore from Paris in 1803. A widow with two children, she

worked as a tutor and set about a project to sustain her French cultural

heritage by publishing a collection of songs and piano pieces that would

appeal to other French ÈmigrÈs for study and performance. The collection

included a large proportion of transcriptions from the latest productions

at the OpÈra-Comique, including arrangements for solo keyboard from the

overtures and interludes of Isouard’s Les confidences (1803) and,

drawing upon one of the era’s most popular vocal forms, a transcription of

the ‘romance’ from Isouard’s first great success, Michel-Ange

(1802).

[6]

Isouard and his contemporaries were also all the rage on the Russian stage

in the early 1800s. Among Isouard’s works that reached Moscow were L’intrigue aux fenÍtres (1807), Le mÈdecin litre

(1810), and Cendrillon (1811). And, Russian literature did not

neglect him: in Alexander Pushkin’s ‘The Blizzard’ from The Tales of the Late Ivan Petrovich Belkin, one of the principal

characters, describing his experience in the army during the Napoleonic

invasion of Russia, refers to Isouard’s Joconde of 1814:

“Meanwhile, the war had ended in glory. Our regiments were returning from

abroad. People ran to meet them. For music they played conquered songs:

Vive Henri-Quatre, Tyrolean waltzes, and arias from Joconde.” Not

everyone was so enamoured of the man and his music, though. Carl Maria von

Weber thought that Cendrillon’s ‘sweet airs’ possessed ‘nothing to

make an effect on an audience’ and criticised ‘the routine nature of

practically every piece’ in the opera and its ‘clumsy instrumentation’.

[7]

Alidor (Nicholas Merryweather) and Cinderella (Kate Howden), Bampton Classical Opera 2018

Alidor (Nicholas Merryweather) and Cinderella (Kate Howden), Bampton Classical Opera 2018

Some have argued that the artlessness of Cinderella’s musical

characterisation – the unadorned melodic line of the simple romances –

reflects the influence of the rather limited vocal talents of Alexandrine

Saint-Aubin, whose celebrated but brief career was given initial impetus by

this role (sung in Bampton’s production by Kate Howden). But, the decorum

of Cinderella’s strophic songs complements her inner grace, and Isouard

reserves the virtuosity for the two stepsisters, Clorinde and Tisbe (here

Aoife O’Sullivan and Jenny Stafford respectively), who, vain, spoiled and

self-promoting, pull out all the coloratura stops when seeking to attract

the Prince’s attention. Clearly, Isouard had an instinctive sense of how to

match melody and context, and, judging by the concerto elements in the

opera’s overture as well as interesting use of harp and horn throughout, a

good ear for musical colour and pictorialism. There is dramatic interest

and depth, too, in the expanded role for Alidoro, the Prince’s sage and

tutor (played by Nicholas Merryweather in this production).

When Isouard died, at the age of 44, in Paris on 23rd March

1818, his final opera Aladin, ou La lampe merveilleuse was

unfinished. Completed by Benincori, the work was premiËred at the OpÈra on

6th February 1822, the first opera in Paris to be produced with

gas lighting, and to include an ophicleide in the pit orchestra. But, on 25 th January 1817, an opera had been performed at the Teatro Valle

in Rome which in the coming years would supplant his own Cendrillon: Rossini’s two-act dramma giocoso, La Cenerentola – the libretto of which

acknowledged a debt to Isouard, declaring itself ‘by Jacopo Ferretti after

Charles Perrault’s Cendrillon and librettos by Charles-Guillaume

Etienne for Nicolas Isouard’s Cendrillon (1810, Paris) and

Francesco Fiorini for Stefano Pavesi’s Agatina, o La virt˘ premiata (1814, Milan)’.

Just as Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven came to dominate instrumental music, so

Rossini, Donizetti and Bellini were predominant in the operatic repertory

by the 1840s. But despite this, other composers continued to achieve

‘popular’ success throughout the nineteenth century, not least as providers

of vocal music to alternate with instrumental works on the concert

programmes of the growing number of subscription societies. Though their

music is infrequently heard today, the most popular – Giovanni Pergolesi,

Giovanni Paisiello, Domenico Cimarosa – remain familiar names. Yet,

composers such as Louis Spohr, Giovanni Viotti, Etienne-Nicolas MÈhul,

George Onslow and Robert Franz are now largely excised from music history,

even though in their day their music – alongside that of Nicolas Isouard –

was whistled on the streets.

Although the OpÈra-Comique revived Les rendez-vous bourgeois and Joconde after World War I, Isouard’s operas have largely

languished in obscurity for more than one hundred years, though in 1999 the

Australian conductor Richard Bonynge presented Cendrillon in

Moscow, a performance that was recorded live. Last year, Manhattan School

of Music mounted a production, and in June this year, Cendrillon

premiered in Malta itself, in the Manoel Theatre in Valletta (which is the

2018 Cultural Capital of Europe).

Thanks to Bampton Classical Opera, we will have an opportunity to hear in

London music that was recalled so fondly by an anonymous writer in the 15 th May 1854 issue of Revue des deux mondes:

‘I was present a few years ago when Cinderella was rehearsing at

the OpÈra-Comique, and I was delighted, I will admit, by the charming

nature of this so naively romantic inspiration. NicolÚ produced an effect

on me that Rossini’s music in all its pomp had not been able to produce. I

seemed to hear a real fairy tale in music, and I found in these slightly

shortened phrases, an expression so simple and so touching, [an] air of

childish grace and good-naturedness …’

Claire Seymour

[1]

Expelled from Rhodes by the Turks in 1523, the Sovereign Military

Order of Malta proved itself a notable musical patron, transforming

Maltese cultural life by introducing European customs and taste.

The Order’s musical establishment in its church in Valetta employed

musicians of considerable talent and a number of distinguished

musicians were associated with the Order. See Duane Galles,

‘Chivalric Orders as Musical Patrons’, Sacred Music, Fall

2012, Vol.139, No.3: 25-44.

[2]

Bruce R. Schueneman and MarÌa De Jes˙s Ayala-Schueneman, ‘The

Composers’ House: Le Magasin De Musique De Cherubini, MÈhul, R.

Kreutzer, Rode, Nicolo Isouard, Et BoÔeldieu’, Fontes Artis Musicae, Vol.51, No 1, 2004: 53-73.

[3]

Geoffrey ¡lvarez, ‘The singing island’, Musical Times,

Vol.157, Iss.1937, (Winter 2016): 114-117.

[4]

In ‘Musical Life in Paris (1817-1848): A Chapter from the Memoirs

of Sophie Augustine Leo-Part I’, The Musical Quarterly,

Vol.17, No.2 (Apr., 1931): 259-271

[5]

Otto E. Albrecht, ‘Opera in Philadelphia, 1800-1830’, Journal of the American Musicological Society, Vol.32,

No.3 (Autumn, 1979): 499-515.

[6]

Elise K. Kirk, ‘Charlotte Le Pelletier’s Journal of Musick

(1810): A New Look at French Culture in Early America’, American Music, Vol.29, No.2 (Summer 2011): 203-228.

[7]

J. Warrack, ed.: Carl Maria von Weber: Writings on Music

(Cambridge, 1981).

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Bolero%20-%20Alidor%20and%20Tisbe%2C%20Dandini%20and%20Clorinde.jpg

image_description=Isouard’s Cinderella, Bampton Classical Opera 2018

product=yes

product_title=Isouard’s Cinderella, Bampton Classical Opera 2018

product_by=A preview by Claire Seymour

product_id=Above: Alidor (Nicholas Merryweather), Tisbe (Jenny Stafford), Dandini (Benjamin Durrant) and Clorinde (Aoife O’Sullivan) dance a Bolero

Bampton Classical Opera Goes to the Ball

American author Gail Carson Levine’s award-winning fantasy-novelElla Enchanted was published in 1997, and as recently as 2015 Walt Disney Pictures revisited the romantic fantasy, producing a

live-action re-imagining of the original 1950 animated film. Both a

Filipino pop group that rose to prominence in the 1970s, and an American

glam rock band formed in Pennsylvania in 1982 and which had a series of

multi-platinum albums and hit singles, chose to call themselves after the

undervalued skivvy.

According to some sources, there are over 1500 adaptations of the Cinderella story, the earliest version of which is usually

considered to be the Greek philosopher Strabo’s account of a Greek slave

girl who marries the Egyptian King. Made popular by Charles Perrault in Histoires ou contes du temps passÈ in 1697 and subsequently by the

Brothers Grimm in their ‘darker’ version of the folk tale (in

‘Aschenputtel’, published in the collected Fairy Tales of 1812,

the step-sisters are so grotesquely greedy that they are willing to hack

bits off their feet to force them into the slipper!), Cinders’ true virtue

has earned its just reward in countless pantomimes and plays, ballets and

films, musicals and novels.

The earliest known British pantomime based on Cinderella was first

performed at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in London in 1904, and now Baron

Hard-Up, the Ugly Sisters and Buttons are perennial Christmas favourites.

In 1957 Rodgers and Hammerstein gave us a television musical with Julie

Andrews in the eponymous role. Prokofiev put the glass slipper en pointe, though Tchaikovsky almost got there first, writing to

his brother Modest in October 1870, ‘Just imagine, that I’ve undertaken to

write the music for a ballet Cinderella, and that this vast

four-act score must be ready by the middle of December!’, though this

commission for his first ballet remained unfulfilled. Ferdinand Langer

(1878), Johann Strauss II (1901) and Frank Martin (1941) have all taken

Cinders to a ballet-ball; and, Christopher Wheeldon, who in 2013 added

puppetry (by Basil Twist) to Prokofiev’s score, will choreograph a new

production of Cinderella, co-produced by English National Ballet

and the Royal Albert Hall where it will be performed in the round in June

next year, which is being billed as ‘the ballet spectacular of 2019’.

Cinemas have offered sugary sweet adaptations of the young girl’s journey

from misery to matrimony, such as The Slipper and the Rose

(starring Richard Chamberlain and Gemma Craven, 1976) and Ever After (1998, featuring Drew Barrymore). And, of course, in

the opera house numerous composers have literally given Cinderella a

‘voice’, from Jean-Louis Laruette and Louis Anseaume (1759) to Stefano

Pavesi (1814), from Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari (1900) to Gustav Holst (1901),

from Peter Maxwell Davies (1979) to

Alma Deutscher

(2016), among others.

Of course, the operatic versions of Goodness Triumphant by Giacomo Rossini

(La Cenerentola, 1817) and Massenet (Cendrillon, 1894-6)

are the best-known. But, in the early nineteenth century it was not Rossini

whose Cinderella was most celebrated but that of the Franco-Maltese Nicolas

– or NicolÚ, as he called himself – Isouard, whose three-act comic opera, Cendrillon, to a libretto by Charles-Guillaume Etienne

after Charles Perrault, was premiered in the Salle Feydeau at the

OpÈra-Comique on 22nd February 1810. And, it is this opÈra-fÈerie by Isouard, who died two hundred years ago, that Bampton Classical Opera –

celebrating their twenty-fifth year – have selected for their 2018

production and which, following performances earlier this summer at Bampton

and Westonbirt, can now be enjoyed at

St John’s Smith Square on 18th September

.

So, who was NicolÚ Isouard, this composer of more than 40 operas, whose

bust graces the pediments of the Palais Garnier in Paris? The son of a

Marseille merchant, Isouard was born in Valletta on 18th May

1773 (according to Grove; some sources suggest 6th December

1775). His early education, which included mathematics, Latin and music,

took place in Paris at the Pensionnat Berthaud, a preparatory school for

the Engineers and Artillery, but the Revolution forced him to flee back to

Malta in 1789 where his father found him a position in a merchant’s office.

He continued his musical studies – composition with Michel-Ange Vella and

counterpoint with Francesco Azzopardi; when his work took him to Palermo,

he took harmony lessons with Giuseppe Amendola; later, in Naples, he

completed composition studies with Nicola Sala and received practical

advice from Guglielmi.

Isouard made his debut as an opera composer with L’avviso ai maritati in June 1794, which was successfully received

in Florence and later given in Lisbon, Dresden and Madrid. Back home, not

all spoke favourably of Isouard, some questioning his masonic affiliations.

In April 1794, the Maltese Inquisition was told that the composer was ‘a

young man who leads a sinful life, frequenting loose women, and boasting

about it. He ridicules and despises the sacrifice of the Mass […] those

acquainted with him consider him a libertine’, but despite such

condemnation, in 1795, on the death of Vincenzo Anfossi, Isouard was

appointed organist to the Order of St John of Jerusalem in Valetta, later

becoming maestro di cappella there. He settled in Malta, composing serious

and comic operas for the Maltese theatre.

[1]

The French invasion of the island in June saw him become secretary to the

Governor of the French garrison, Vaubois, and following the French

submission to the British, Isouard, perhaps fearful of charges of

collaboration, returned with the latter to Paris in 1799. His first

Parisian opÈra comique, Le petit page, composed

in collaboration with Rodolphe Kreutzer who acted as Isouard’s manager and

patron, was given in the ThȂtre Feydeau in February 1800. Friendship with

the librettist F.-B. Hoffman led to the sharpening of his dramatic insight,

and his first major success came with Michel-Ange (1802).

On 5th August 1802, Isouard co-founded – with Luigi Cherubini,

Etienne-Nicolas MÈhul, Rodolphe Kreutzer, Adrien BoÔeldieu and Pierre Rode

– Le magasin de musique dirigÈ, a publishing venture which

formally opened in December that year, in premises at 268 rue de la Loi in Paris (in 1805-6 the street number and name were

altered to 76 rue de Richelieu). The company was designed to spare

composers – who in the late-eighteenth century habitually self-published

their works and sold them personally or through music shops – from

financial risk and time-consuming business matters, and to ensure that they

received increased publicity and profit. Each of the six composers was

contracted to furnish at least one opera or 50 pages of music each year,

and each was entitled to the proceeds from the sale of his own works and to

a share in the profits of the firm’s publications of works, mainly

instrumental compositions, by various non-associated contemporary composers

who were popular in Paris at the time.

In total more than 650 editions were published, from engraved plates,

including Viotti’s five violin concertos and, notably, the first edition in

full score of Le nozze di Figaro (1807-08). However, of the six

collaborators Isouard – who had the most extensive business experience

among the group – was alone in taking his prescribed obligations seriously:

the firm printed nine of his operas in full score, alongside Cherubini’sAnacrÈon, MÈhul’s Joseph and BoÔeldieu’s Ma tante Aurore. He left the firm in July 1807 and on 12 August

1811 the partnership was dissolved, J.-J. Frey acquiring the business,

manuscripts and 9679 engraved plates (of which Isouard’s contribution

accounted for 3,553 engraved pages, about 37% of the total).

[2]

In 1808, with Un jour ‡ Paris, Isouard began his long

collaboration with Etienne, who was the editor of the Journal des deux mondes. Two years later they had an unprecedented

success at the OpÈra-Comique in 1810 with the fairy-tale operaCendrillon, and further triumphs followed including Jeannot et Colin (1814) and Joconde (1814), the latter

establishing Isouard’s international reputation. He had little serious

competition among his fellow composers in Paris at this time, but with the

return of BoÔedlieu, from Russia, in 1811, a friendly rivalry was

initiated, one which became more acrimonious when both applied for

membership of the Institut de France (1817). BoÔeldieu’s success angered

Isouard who broke off relations with his former friend. Indeed, it has been

suggested that Isouard was driven to drink, debauchery and an early death

by his jealousy of BoÔeldieu!

[3]

Isouard, BoÔeldieu and MÈhul are often credited with having brought French opÈra comique to its final form. The genre is a significant marker

of changing taste in France in the early years of the nineteenth century.

While the French did share Napoleon’s liking for Italian opera and

aristocratic themes, opÈra comique

came to be strongly identified with the cultural appetites of the

post-revolutionary bourgeoisie who, after years of Revolutionary

turmoil and bloodshed, now longed for simple entertainments that would

amuse and bring joy. Characters were drawn from everyday life; plots

involved complicated deceptions and subterfuges; a pair of lovers was

unfailingly at the centre of the drama. The story was advanced by

spoken dialogue and the music was ‘uncomplicated’: melodious strophic

airs and romances, pictorial orchestrations, strongly defined musical

characterisation.

Though the genre is occasionally dismissed as light and trivial, both

Edward J. Dent and Donald Grout argue that it is in the op Èra-comique of the years from 1790 to 1815 that we should look for

the origins of mid-nineteenth-century Romantic grand opera.

Isouard certainly achieved great popularity at home and abroad during his

life-time. His operas were performed across Europe; Michel-Ange

was translated into five languages and L’intrigue aux fenÍtres

into seven. Born in Hanover in 1795, Sophie Augustine Leo, the writer of

the anonymous Erinnerungen aus Paris (Berlin, 1851), had travelled

to Paris with her elder sister Mme Valentin in 1817, and the year later

married the German banker August Leo, a prominent patron of the arts among

whose regular guests were many distinguished artists living in Paris at

this time. Writing of the ‘masterpieces’ that were being given at the

OpÈra-Comique during this period, Sophie remarked Isouard’s achievements:

‘His opera Jeannot et Colin, more especially his Rendezvous bourgeois, sparkled with life and animation; I doubt

whether a more amusing subject than the latter is to be found. Though I can

no longer remember enough of the detail to retell the story, I know that

the merriment of the spectators was endless and that the music had caught

the spirit of the text. L’intrigue aux fenÍtres followed, then Cendrillon and Joconde, and Isouard died, aged forty-one,

at the height of his development and in the ever increasing favor of his

public.’

[4]

She also noted that, ‘In 1818, i.e., shortly after my arrival in Paris,

connoisseurs were shocked by the deaths of Isouard and MÈhul’.

Frequently composers made adaptations and transcriptions of Isouard opera

airs. In 1810 Jan Ladislav Dussek published his “Variations No.4 in G major

on ‘Toto Carabo’ or ‘Il Ètoit un petit homme’ from the opera Cendrillon by NicolÚ Isouard arranged as a Rondo with Imitations”,

and one of Johann Nepomuk Hummel’s seven sets of variations on opera themes

took Cendrillon as its source.

Isoaurd’s fame and favour reached far afield. In his study of opera in

Philadelphia from 1800-30, Otto Albrecht demonstrates that Isouard’s work

was popular among the 258 different operas presented during in the city

during these thirty-one years. In October 1827 no fewer than three operas

by Isouard were performed: Cendrillon, ou Le petit soulier verd (first performed on 20th

October 1827) was preceded by Joconde, ou Les coureurs d’aventures

(1st October) and Les rendez-vous bourgeois (17 th October), while a year later on 18th October 1828

Isouard’s Lully et Quinault, ou Le dÈjeuner impossible was staged.

[5]

Further evidence of the dispersal of Isouard’s music in America can be

found in Charlotte le Pelletier’s ambitious Journal of Musick,

published in Baltimore in 1810. Pellier, a pianist and composer, had

arrived in Baltimore from Paris in 1803. A widow with two children, she

worked as a tutor and set about a project to sustain her French cultural

heritage by publishing a collection of songs and piano pieces that would

appeal to other French ÈmigrÈs for study and performance. The collection

included a large proportion of transcriptions from the latest productions

at the OpÈra-Comique, including arrangements for solo keyboard from the

overtures and interludes of Isouard’s Les confidences (1803) and,

drawing upon one of the era’s most popular vocal forms, a transcription of

the ‘romance’ from Isouard’s first great success, Michel-Ange

(1802).

[6]

Isouard and his contemporaries were also all the rage on the Russian stage

in the early 1800s. Among Isouard’s works that reached Moscow were L’intrigue aux fenÍtres (1807), Le mÈdecin litre

(1810), and Cendrillon (1811). And, Russian literature did not

neglect him: in Alexander Pushkin’s ‘The Blizzard’ from The Tales of the Late Ivan Petrovich Belkin, one of the principal

characters, describing his experience in the army during the Napoleonic

invasion of Russia, refers to Isouard’s Joconde of 1814:

“Meanwhile, the war had ended in glory. Our regiments were returning from

abroad. People ran to meet them. For music they played conquered songs:

Vive Henri-Quatre, Tyrolean waltzes, and arias from Joconde.” Not

everyone was so enamoured of the man and his music, though. Carl Maria von

Weber thought that Cendrillon’s ‘sweet airs’ possessed ‘nothing to

make an effect on an audience’ and criticised ‘the routine nature of

practically every piece’ in the opera and its ‘clumsy instrumentation’.

[7]

Some have argued that the artlessness of Cinderella’s musical

characterisation – the unadorned melodic line of the simple romances –

reflects the influence of the rather limited vocal talents of Alexandrine

Saint-Aubin, whose celebrated but brief career was given initial impetus by

this role (sung in Bampton’s production by Kate Howden). But, the decorum

of Cinderella’s strophic songs complements her inner grace, and Isouard

reserves the virtuosity for the two stepsisters, Clorinde and Tisbe (here

Aoife O’Sullivan and Jenny Stafford respectively), who, vain, spoiled and

self-promoting, pull out all the coloratura stops when seeking to attract

the Prince’s attention. Clearly, Isouard had an instinctive sense of how to

match melody and context, and, judging by the concerto elements in the

opera’s overture as well as interesting use of harp and horn throughout, a

good ear for musical colour and pictorialism. There is dramatic interest

and depth, too, in the expanded role for Alidoro, the Prince’s sage and

tutor (played by Nicholas Merryweather in this production).

When Isouard died, at the age of 44, in Paris on 23rd March

1818, his final opera Aladin, ou La lampe merveilleuse was

unfinished. Completed by Benincori, the work was premiËred at the OpÈra on

6th February 1822, the first opera in Paris to be produced with

gas lighting, and to include an ophicleide in the pit orchestra. But, on 25 th January 1817, an opera had been performed at the Teatro Valle

in Rome which in the coming years would supplant his own Cendrillon: Rossini’s two-act dramma giocoso, La Cenerentola – the libretto of which

acknowledged a debt to Isouard, declaring itself ‘by Jacopo Ferretti after

Charles Perrault’s Cendrillon and librettos by Charles-Guillaume

Etienne for Nicolas Isouard’s Cendrillon (1810, Paris) and

Francesco Fiorini for Stefano Pavesi’s Agatina, o La virt˘ premiata (1814, Milan)’.

Just as Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven came to dominate instrumental music, so

Rossini, Donizetti and Bellini were predominant in the operatic repertory

by the 1840s. But despite this, other composers continued to achieve

‘popular’ success throughout the nineteenth century, not least as providers

of vocal music to alternate with instrumental works on the concert

programmes of the growing number of subscription societies. Though their

music is infrequently heard today, the most popular – Giovanni Pergolesi,

Giovanni Paisiello, Domenico Cimarosa – remain familiar names. Yet,

composers such as Louis Spohr, Giovanni Viotti, Etienne-Nicolas MÈhul,

George Onslow and Robert Franz are now largely excised from music history,

even though in their day their music – alongside that of Nicolas Isouard –

was whistled on the streets.

Although the OpÈra-Comique revived Les rendez-vous bourgeois and Joconde after World War I, Isouard’s operas have largely

languished in obscurity for more than one hundred years, though in 1999 the

Australian conductor Richard Bonynge presented Cendrillon in

Moscow, a performance that was recorded live. Last year, Manhattan School

of Music mounted a production, and in June this year, Cendrillon

premiered in Malta itself, in the Manoel Theatre in Valletta (which is the

2018 Cultural Capital of Europe).

Thanks to Bampton Classical Opera, we will have an opportunity to hear in

London music that was recalled so fondly by an anonymous writer in the 15 th May 1854 issue of Revue des deux mondes:

‘I was present a few years ago when Cinderella was rehearsing at

the OpÈra-Comique, and I was delighted, I will admit, by the charming

nature of this so naively romantic inspiration. NicolÚ produced an effect

on me that Rossini’s music in all its pomp had not been able to produce. I

seemed to hear a real fairy tale in music, and I found in these slightly

shortened phrases, an expression so simple and so touching, [an] air of

childish grace and good-naturedness …’

Claire Seymour

[1]

Expelled from Rhodes by the Turks in 1523, the Sovereign Military

Order of Malta proved itself a notable musical patron, transforming

Maltese cultural life by introducing European customs and taste.

The Order’s musical establishment in its church in Valetta employed

musicians of considerable talent and a number of distinguished

musicians were associated with the Order. See Duane Galles,

‘Chivalric Orders as Musical Patrons’, Sacred Music, Fall

2012, Vol.139, No.3: 25-44.

[2]

Bruce R. Schueneman and MarÌa De Jes˙s Ayala-Schueneman, ‘The

Composers’ House: Le Magasin De Musique De Cherubini, MÈhul, R.

Kreutzer, Rode, Nicolo Isouard, Et BoÔeldieu’, Fontes Artis Musicae, Vol.51, No 1, 2004: 53-73.

[3]

Geoffrey ¡lvarez, ‘The singing island’, Musical Times,

Vol.157, Iss.1937, (Winter 2016): 114-117.

[4]

In ‘Musical Life in Paris (1817-1848): A Chapter from the Memoirs

of Sophie Augustine Leo-Part I’, The Musical Quarterly,

Vol.17, No.2 (Apr., 1931): 259-271

[5]

Otto E. Albrecht, ‘Opera in Philadelphia, 1800-1830’, Journal of the American Musicological Society, Vol.32,

No.3 (Autumn, 1979): 499-515.

[6]

Elise K. Kirk, ‘Charlotte Le Pelletier’s Journal of Musick

(1810): A New Look at French Culture in Early America’, American Music, Vol.29, No.2 (Summer 2011): 203-228.

[7]

J. Warrack, ed.: Carl Maria von Weber: Writings on Music

(Cambridge, 1981).

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Bolero%20-%20Alidor%20and%20Tisbe%2C%20Dandini%20and%20Clorinde.jpg

image_description=Isouard’s Cinderella, Bampton Classical Opera 2018

product=yes

product_title=Isouard’s Cinderella, Bampton Classical Opera 2018

product_by=A preview by Claire Seymour

product_id=Above: Alidor (Nicholas Merryweather), Tisbe (Jenny Stafford), Dandini (Benjamin Durrant) and Clorinde (Aoife O’Sullivan) dance a Bolero