This led not to the political and patriotic work that Verdi wished for but

to an essentially domestic drama based on a play by Schiller; the first

time Verdi had worked on a purely bourgeois drama. And the longer gestation

time allowed Verdi to experiment with ideas learned whilst he was in Paris

supervising his opera Jerusalem, so Luisa Miller makes a

far greater, and more sophisticated use of the orchestra including two

substantial orchestrally accompanied recitatives, and has a new flexibility

when it comes to form. We can feel Verdi, almost for the first time,

shaping the music to the drama rather than fitting it into pre-existing

conventional forms.

The opera, however, is perhaps harder to love than the three operas which

came after it, Rigoletto, Il trovatore, La traviata; the characters are all in some way unsympathetic

except for Luisa herself. So, it tends to be an opera which is admired and

revered rather than loved. Certainly, it has not been seen much on the

London stage; there was a rather old-fashioned Filippo Sanjust production

at Covent Garden in 1978 which received its final revival in 1981, and then

a modish Olivier Tambosi production there in 2003 which was never revived.

Apart from that there hasn’t been much else beyond valuable concert

performances from other opera groups. I was lucky enough to see the work at

the Metropolitan Opera in New York in the 1980s with Luciano Pavarotti as

Rodolfo, again in a very traditional production. None of these, however,

seemed to be able to make a strong case for the piece as drama.

For the new production of Verdi’s Luisa Miller at the London

Coliseum, English National Opera invited the young Czech director Barbora

Hor·kov·, and drew together a strong cast with Elizabeth Llewellyn making a

welcome appearance in the UK as Luisa, David Junghoon Kim as Rodolfo,

Olafur Sigurdarson as Miller (his ENO debut), James Creswell as Count

Walter, Soloman Howard as Wurm, Christine Rice as Federica and Nadine

Benjamin as Laura. Sets were by Andrew Lieberman with costumes by Eva-Maria

Van Acker, choreography by James Rosental, lighting by Michael Bauer.

Alexander Joel conducted. The translation was by Martin Fitzpatrick.

Barbora Hor·kov· was a finalist and prizewinner at the Ring Award Graz in

2017 and received the Best Newcomer Award at the 2018 International Opera

Awards. We caught her production of Verdi’s early comedyUn giorno di regno at the Heidenheim Festival in 2017. Luisa Miller was a co-production with Oper Wuppertal where it has

already been performed, but in an article in the programme book Hor·kov·

made it clear that the production had been extensively re-worked (and

re-designed) for London (a glance at the Wuppertal production photos in the

programme book confirmed this).

The plot is a mixture of family drama and class struggle. Miller (Olafur

Sigurdarson) is a retired soldier who expects his young daughter Luisa

(Elizabeth Llewellyn) to be a comfort in his old age and is opposed to her

being wooed by the mysterious Carlo (David Junghoon Kim). Carlo is in fact

Rodolfo, the son of Count Walter (James Creswell), the local lord of the

manor. Walter and Rodolfo are at odds, and Walter has a guilty secret, his

murder of his cousin enabled Walter to inherit the estate. Central to this

is Walter’s steward Wurm (Soloman Howard) who lusts after Luisa himself,

and a complicating factor is that the young Rodolfo witnessed the murder.

Of course, it ends badly.

David Junghoon Kim. Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

David Junghoon Kim. Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

Hor·kov· told the story with clarity, and with no additions and

subtractions; she told the story with and through the music (her only

alteration was that Wurm did not die at the end). Her chosen language was

that of European regie-theater, a style which we do not see

regularly in the UK. It is perhaps worth bearing in mind that Hor·kov·’s

theatrical language would be familiar to many of the opera-goers in

Wuppertal. It is also worth bearing in mind a comment by Bernard Haitink.

He conducted the Richard Jones production of Wagner’s Ring Cycle

at Covent Garden; though Haitink famously had doubts about the production,

he conducted it because Jones drew such superb performances from the

singers and said that it was impossible to dissociate the production from

the musical values. So, coming out of this production saying we enjoyed the

singing but disliked the production style is doing Hor·kov· a disservice.

Whilst I have no particular enthusiasm for this style of production, I have

no objection to it either. As I have said, Hor·kov· told the story with

clarity and drew strong performances from her cast as she drilled down into

the more complex psychological underpinning of the story. Though it is

clear from the interview with her in the programme book that every detail

meant something, the visual style of the production was rather too

cluttered, what with clowns, balloons, two children representing the more

innocent side of Luisa and Rodolfo, dancers who according to Hor·kov·

represented the Darkness which was personified by Wurm, the white walls on

which people scrawled, the ubiquitous use of a tar-like substance which

seemed to get everywhere.

But this emphasis on the psychological paid dividends in the performances

which were outstanding, and for the first time I experienced Luisa Miller as riveting drama. It helped that for Acts Two and

Three, Hor·kov· allowed us to concentrate on the singers and these two had

a far greater sense of focussed drama. We should also bear in mind the

negative benefits of Hor·kov·’s style, the production lacked the

trivialising prettiness of a traditional staging, she stuck to the story

and didn’t give us her version of Luisa Miller, and there was no

over-sexualisation of the plot. Eva-Maria Van Acker’s costumes, whilst

being of mixed eras and styles (including the chorus in vaguely clown-like

Day of the Dead style), gave us a clear distinction of the class layers in

this work. Class is important in many 19th century operas, and too many

opera directors tend to play this factor down. And those white walls,

whilst writing on white walls is a bit of a tired trope I did love the way

that black dribbled down them in the second half, giving us a visual

metaphor for the way the Darkness encroached. Though the cleaning and

laundry bill each night must be huge!

Olafur Sigurdarson, Elizabeth Llewellyn. Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

Olafur Sigurdarson, Elizabeth Llewellyn. Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

Technically there are three leading roles (Miller, Luisa, Rodolfo) and

three smaller ones (Walter, Wurm, Federica), but the smaller ones received

such strong performances here that we had little sense of this hierarchy,

instead there was a superb ensemble feel supporting strong individual

performances.

Elizabeth Llewellyn was outstanding as Luisa, a young woman who has to grow

up quickly and face the real world. She had the flexibility to sing Luisa’s

often elaborate vocal writing whilst being able to draw out a strong,

shapely vocal line. She also conveyed Luisa’s psychological journey with

great intensity, Llewellyn is a singer who is able to convey much with face

and with eyes, this was an intense and gripping experience.

She was well partnered by David Junghoon Kim as Rodolfo. Kim was vivid and

tireless in the role, and whilst he did not have the ideal open-throated

Italianate sound, he sang with a wonderful intensity whilst giving us a

gorgeous mezza-voce for his cavatina at the beginning of Act Three. We

never really see Luisa and Rodolfo/Carlo in happier times, but their final

long scene as the two lay dying was transcendently magical. The men in the

opera are all various types of shit. Whilst Rodolfo happily dupes Luisa, he

immediately jumps to conclusions when things go wrong for her.

Her father, by contrast is simply a selfish old git, he pretends to be

concerned for her welfare, but he really wants her as a comfort for his old

age. Olafur Sigurdarson managed to make the character human, if not

entirely sympathetic, and in Act Three when released from prison both he

and Llewellyn captured the sense of trauma that the characters have gone

through. Sigurdarson’s singing was admirably strong and focused, with a

great feeling for Verdi’s line though there were moments when I worried

that he was trying a bit too hard.

Wurm is traditionally portrayed as ugly in some way so that his exterior

matches his evil interior, but Soloman Howard’s Wurm was anything but.

Tall, handsome, physically fit (we got a good view of his upper body

muscles) and sexy, Howard was completely mesmerising and disturbing. On

stage for a good bit of the time, Howard’s presence as Wurm radiated his

sense of control and contributed considerably to the character’s

omnipresence in the plot. Howard sang with a fine, dark line making Wurm as

vocally seductive as he was physically, this was an amoral character whom

it would be difficult to resist.

Christine Rice. Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

Christine Rice. Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

James Creswell had a different, but equally strong presence as Count

Walter; Creswell was the embodiment of entitlement as well as a certain

amorality, but also an underlying weakness which was his downfall.

Christine Rice was a complete delight as Federica, and we wished Verdi had

got his way and made more of the character. Nadine Benjamin, in fine voice,

seized her moments as Luisa’s friend Laura. Adam Sullivan (a member of the

ENO Chorus) gave sterling support as a citizen (in the original, a

peasant).

Perhaps more important than individual performances was the terrific

feeling of interaction between these, so that the duets and ensembles fair

crackled, the dialogue gripped and flowed particularly the scenes between

Miller and Luisa, and Luisa and Rodolfo in the last act, creating some fine

musical drama.

Andrew Lieberman’s sets with their large flat surfaces provided valuable

support to the singers, and the expanded ENO Chorus was in terrific form.

This was one of the first operas in which Verdi actually made the chorus

part of the action; here they are fellow villagers, and the chorus members

really seized their opportunities and created a strong dramatic presence.

In the pit, Alexander Joel drew impressive playing from the orchestra, this

was an impulsive and dramatic performance. Joel clearly knows and

understands Verdi, and this was an account of the opera where the drama and

the music were linked, so that moments like Verdi’s important long

recitative sections were finely fluid, whilst the big moments were

thrilling.

By the end of this evening it was impossible not to be gripped by the

drama, and to be fully engaged by the music. ENO had put together a strong

cast, and Joel and Hor·kov· drew from them some thrilling drama and very

fine Verdi singing indeed.

Robert Hugill

Verdi: Luisa Miller

Count Walter – James Creswell, Rodolfo – David Junghoon Kim, Federica –

Christine Rice. Wurm – Soloman Howard, Miller – Olafur Sigurdarson, Luisa –

Elizabeth Llewellyn, Laura – Nadine Benjamin, A Citizen – Adam Sullivan,

Dancers (Stephanie Bentley, Sam Ford, Anna Holmes, John William Watson),

Children (William Barber/David Cummings, Halle Cassell/Taziva-Faye

Katsande); Director – Barbora Hor·kov·, Conductor – Alexander Joel, Set

Designer – Andrew Lieberman, Costume Designer – Eva-Maria Van Acker,

Lighting Designer – Michael Bauer, Choreographer – James Rosental,

Orchestra and Chorus of English National Opera.

English National Opera, London Coliseum; Saturday 15th February

2020.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Nadine%20Benjamin%2C%20Elizabeth%20Llewellyn%2C%20Soloman%20Howard%2C%20.jpg

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=Luisa Miller, at English National Opera

product_by=A review by Robert Hugill

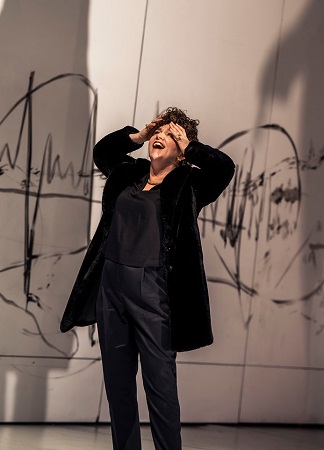

product_id=Above: Nadine Benjamin, Elizabeth Llewellyn and Soloman Howard.

Photo credit: Tristram Kenton