It’s probably fair to say that Latvian composers don’t feature greatly on even the most avid classical music aficionado’s radar. When I reflect, only the names of Ēriks Ešenvalds and Pēteris Vasks come readily to mind. So, soprano Inga Kalna’s debut solo disc, with her long-term collaborator, pianist Diana Ketler, offers an intriguing programme. For, Das Rosenband, which was recorded in the Great Amber Concert Hall in Liepāja, Lavtia in July 2020, places the little-known music of two turn-of-the-century Latvian composers, Alfrēds Kalninš (1879-1951) and Jānis Medinš (1890-1966), alongside familiar songs by Richard Strauss. The programme was first heard in 2016, when Kalna and Ketler performed it at the Dzintari Concert Hall in Jūrmala as part of that year’s Autumn Chamber Music Festival – a which concert received the Latvian Grand Music Award in 2016 for best chamber music performance.

It seems astonishing that this is Inga Kalna’s debut solo album, given that her career has taken her to the stages of Hamberg State Opera, the Vienna State Opera, the Opéra National de Paris, La Monniae, La Scala, the Salzburg Festival and many other prestigious venues. Her performances in René Jacobs’ Handel and Mozart projects and under Marc Minkowski’s baton in Handel’s Il trionfo del tempo e del disinganno at the Staatsoper Berlin and Alcina in Paris and London have garnered attention and acclaim. I’ve only heard Kalna sing live once, in Il Pomo d’Oro’s Serse at the Barbican in 2018, and I was impressed. If it might be thought a little surprising that she has chosen to focus upon late-Romantic song on this debut disc, then Kalna demonstrates that her lyric soprano has the necessary weight and sheen, and the Latvian currents which she and Ketler explore are captivating.

Kalninš and Medinš belong to that collection of fine composers who led musical nationalism in Europe in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, but whose compositions didn’t regularly travel beyond their national boundaries and have since been overlooked by musicologists, performers and listeners alike. Interestingly, Kalninš and Medinš also both lived through the communist and fascist occupations of Latvia during the years 1940-45, and witnessed the re-imposition of Soviet rule subsequently.

Grove tells us that Medinš built a career as a violist and conductor later becoming opera conductor of the Latvian National Opera (1920–28), chief conductor of the Latvian RSO and artistic director of Latvian Radio (1928–44). He taught in the orchestration class at the Latvian State Conservatory (1921–44), where he was appointed professor in 1929; in 1932 he became head of orchestral conducting. Medinš fled from the advancing Soviet forces in 1944, briefly living in Germany before settling in Stockholm in 1948. Kalniņš is considered by some to be the founder of Latvian opera, and composed over 250 solo songs, which are often imbued with the spirit of Latvian folk music, if not directly quoting such sources. Though he lived and worked in the US during the period 1927–33, following an invitation to become organist at the Dome cathedral in Riga, he returned to Latvia in 1933. In 1944 he became professor at the Latvian State Conservatory and was rector there between 1944 and 1948.

In an interview with Latvian Radio 3 ‘Klasika’ and the ‘Diena’ newspaper, Kalna described this recital programme as “musical Art Nouveau about the theme of love with extremely poetic imagery. Lots and lots of nature: evening, morning, sunny daytime, night. Autumn leaves and the groaning sea, moonlit waters and a summer evening’s breeze … It has love poetry in all of its aspects: general, sensual and even religious. Love for nature and one’s homeland. Love for one another, for the seasons and for the whole world embracing us. Lots of melancholy longing,” adding that “Mediņš immediately makes me think of Art Nouveau. I see Albert street and Riga’s Art Nouveau buildings.”

A miniature such as Mediņš’ ‘Uz brītiņu’ (For a moment) reveals Kalna’s ability to swiftly traverse a range of emotions and images with vibrancy and immediacy, conveying the excitement and consolation of love, the struggle and strife of life. Her lyric soprano is appealing and flexible; it can float delicately or make its presence felt. In this song, Kalna creates a sense of dipping into the protagonist’s mind, of being utterly immersed in an instant. The folky fourths and ostinato rhythms of Mediņš’ ‘Aicinājums’ (Invitation) are coyly playful, and against the lovely transparency of the piano’s busy textures the lyrical vocal line has radiance, transporting the listener to the world of fairy tale in the third stanza in which “the green spark of dreams/ Shines through the window”.

The rapture of new love acquires an almost spiritual fervour in ‘Jaunā mīla’ before calming and closing with ethereal lightness. In contrast, Mediņš ‘Glāsts’ (The Caress) has a simple directness, the strophic form and rocking piano motif bringing comfort and ease: this is a song to ensure peaceful dreams – think Humperdinck’s ‘Evening Prayer’ with a dash of ecstasy. Mediņš’ ‘Nocturno’ has a barcarolle-like momentum, but subtle nuances in both the voice and piano inject a welcome freedom and lightness of spirit, and Kalna’s lovely diminuendo at the close is finely graded.

Kalniņš’ ‘Efeja vija’ (The ivy) has an aphoristic preciousness – like an imagist poem – and there are some lovely Straussian harmonic slippages. The piano postlude is surprisingly tempestuous but eventually retreats into wistfulness, “what once was”. Kalna makes much of the words, here and throughout the programme, taking trouble to consider and convey their meaning. There is deep ardour in her soprano in Kalniņš’ ‘Jūras vaidi’ (The meaning of the sea) as Kalna explores the rich poetic imagery – “distant days of old I hear the sea roar … foam floods in anger”. The piano accompaniment is tremulous, with restless chromatic rises from the depths, but though the vocal line sinks low at times it remains evocative, overwhelmed only in the closing, clangourous sweep of wild storms and melancholy cries.

Kalniņš’ ‘Ūdens lilija’ is wonderfully fresh and lyrical, the water lily’s beauty as fragile, true and eternal as the moon’s silver rays. In ‘Minjona’ Kalniņš sets Goethe’s ‘Mignon’s song’, conveying the questioning intensity and complexity of the poem. The urgency and desire of the opening stanza culminates in a blissful vocal rise, “I desire to go with you, my beloved”, before memories and visions bring a tumult of emotions, troubled feelings that are finally assuaged with the transcendent salvation offered at the close, “let us go!”. There is a beautiful interplay between the voice and piano in Kalniņš’ ‘Jau aiz kalniem, jau aiz birzēm’ (Beyond the hills, beyond the grove). Here Kalna is a masterful singing storyteller. The melody has a beguiling spontaneity and builds towards the sort of passionate outburst that we might expect from a Jenůfa or Kát’a Kabanová – rapt, free and deeply touching.

These Latvian songs are a real delight, conjuring evocative worlds, seeming to encompass vast spans of time and space within their slender frames, communicating sincere human feeling. Kalna’s selection of Strauss songs are similarly emotive. Ever attentive to the poetic texts, she and Ketler offer some surprising and original interpretative nuances not least in ‘Morgen’ (Tomorrow) where a slow tempo is adopted, and the arpeggiated piano chords and ensuing triplets elongated and rhythmically irregular. This creates a certain timelessness, but as the song progresses I feel that it hinders the fluency of the song, and as the delays and rubatos become more exaggerated, the effect is somewhat mannered. Kalna’s vocal tone is refreshing and brings energy to the song, but the tendency to place emphatic weight on certain syllables seems to go against the simple certainty, and pathos, of the text: “Und auf uns sinkt des Glückes stummes Schweigen …” (And the speechless silence of bliss shall fall on us …)

There are a few slight intonation problems at the close too, and in the final phrase of ‘Allerseelen’ (All Souls’ Day), though here Kalna does capture the wistful melancholy of the harmonic shadows, and melodic sighs and resignation, while maintaining the energy within the vocal line which is propelled forward by the piano’s arpeggio rises. As the poet-speaker retreats into the past, there is a well-judged withdrawal, “Gib nur einen deiner süßen Blicke,/ Wie einst im Mai” (Give me but one of your sweet glances, As once in May.), and great tenderness in the piano postlude. ‘Breit’ über mein Haupt’ (Unbind your black hair) is dignified and direct, and Kalna really makes the listener feel the sublimity of the imagery: “Da strömt in die Seele so hell und klar/ Mir deiner Augen Licht” (Then clearly and brightly into my soul/ The light of your eyes will stream). In contrast, passion surges through ‘Zueignung’ (Dedication), though again I found Ketler’s free rhythmic response to Strauss’s instruction ‘con espressivo’ a little disruptive. Here, too, Kalna sometimes struggles to project the low-lying phrases, the crucial repetition, “Habe danke” (Have thanks) that closes each stanza becoming buried within the piano’s motions. This has the effect of weakening the transfiguration of the conclusion, where the final repetition overcomes the binding minor 3rd and finds release in a major 6th rise. Kalna holds the final note in extended rapture but its preceding springboard is lost.

‘Ruhe, meine Seele!’ (Rest my soul) has a lovely stillness, however. Kalna treats the melody in a recitative-like fashion, ever attentive to the text, while Ketler relishes the musical imagery. And, if the chromatic meanderings of Das Rosenband’ (The rose garland) are sometimes a little imprecise then the sensuous spirit of the song is powerfully conveyed and there is a compelling drive towards consummation. Kalna’s spins the final image of Elysium with heart-touching delicacy and Kelner perfumes this with a celestial sparkle. The recital closes with ‘Cäcilie’, which is fittingly fervent and impassioned.

If Kalna’s Strauss interpretations are not always to my liking, there is no doubting the comforts of her vocal warmth and colour, nor the care with which she treats the text, and she offers plentiful food for thought. And, the affection she bestows upon the songs of her compatriots, Alfrēds Kalninš and Jānis Medinš, make this disc a must have.

Claire Seymour

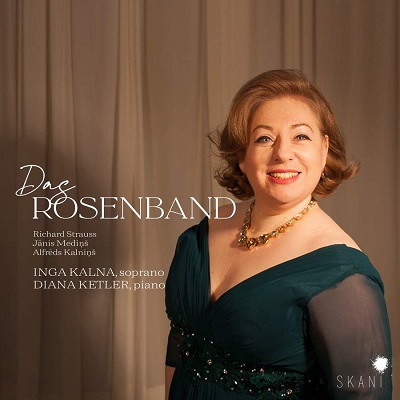

Das Rosenband: Inga Kalna (soprano), Diana Ketler (piano)

R. Strauss: ‘Allerseelen’ Op.10 No.8, ‘Morgen’ Op.27 No.4, ‘Breit’ über mein Haupt’ No.2 Op.19, ‘Zueignung No.1 Op.10, ‘Ruhe, meine Seele!’ Op.27 No.1, ‘Das Rosenband’ No.1 Op.36, ‘Die Nacht’ Op.10 No.3, ‘Heimliche Aufforderung’ No.3 Op.27, ‘Cäcilie’ No.2 Op.27.

Mediņš: ‘Uz brītiņu’, ‘Aicinājums’, ‘Jaunā mīla’, ‘Glāsts’, ‘Nocturno’.

Kalniņš: ‘Efeja vija’, ‘Jūras vaidi’, ‘Ūdens lilija’, ‘Minjona’, ‘Jau aiz kalniem, jau aiz birzēm

SKANI, LMIC083 [50:22]