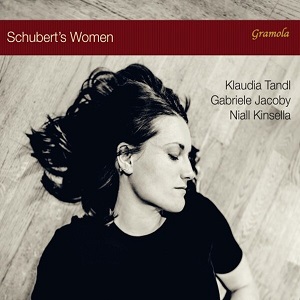

Schubert’s Women, a programme of lieder and poetry,was born from a serendipitous collaborative pairing during a summer lieder master-course at the Franz-Schubert-Institut in Baden in 2017, which brought together the mezzo-soprano Klaudia Tandl and the pianist Niall Kinsella. In his liner booklet introduction, Kinsella explains how, in curating the programme, he aimed to ‘show various aspects of the female character, as understood by Schubert’ in the form of ‘small ‘scenas’, showing shades of longing, innocence, humour, wit, seduction, and utter desolation, with Schubert’s ‘tour-de-force’ lieder for Mignon and Gretchen’. At that 2017 master-course, the actress Gabriele Jacoby had been the duo’s poetry coach, and Kinsella suggests that, ‘Her natural sense of musicality, phrasing, rhythm, and intonation combine to make her recitations of these poems truly captivating, and cause one to hear the songs in a completely different way.’

So, who are ‘Schubert’s women’? Real women whom he with whom he had relationships or who were patronesses? Particular singers and actresses by whom he was inspired? The fictional figures in the literary texts he set – Gretchen, Suleika, Mignon, Ellen, Delphine, Thekla, Amalia, and Schlegel’s ‘Mädchen’? Imagined maidens, mermaids and mothers; ghost, nuns and spinners? There are over 60 lieder by Schubert which give fictional female poetic personae a ‘voice’. There are many more songs which are addressed or dedicated to, or which tell a narrative about, a woman. Schubert’s ‘women’ are many, their lives dramatic, often traumatic, their inner lives – as expressed in his music – complex. A short recital programme cannot fully reflect this depth or diversity, but it can offer some intriguing pathways and reflections.

Schubert’s Women begins, somewhat surprisingly, with Jacoby’s recitation of Ignaz Franz Castelli’s ‘Das Echo’, a rather formulaic ‘echo effect’ poem in which a young girl explains to her angry mother that the ‘echo on yonder hillside’ is to blame for the fact that she was kissed by Hans, to whom she is now engaged to be married. Jacoby reads Castelli’s stanzas with wry relish. It’s a shame not to have Schubert’s setting of it, especially as it isn’t often heard in the recital hall.

Instead, Tandl and Kinsella begin with the disappointment, anger and emotional torment expressed by the betrayed lass in Seidl’s ‘Die Männer sind méchant’, who laments that she did not listen to her mother’s wise words, “Men are naughty”. They capture the young girl’s indignance and self-pity, through the confined vocal phrases, tight rhythms, and the piano’s insistent complaints, while Kinsella’s right-hand trills and decorations suggest the playful passion which the girl witnessed when she espied her former beloved in another’s arms. Tandl’s mezzo-soprano is not a large instrument, and many of the selected lieder have quite a limited tessitura. The recorded balance favours the piano and sometimes Tandl’s lower voice disappears within the accompanying textures. When she pushes her upper register, the tone can become a little hard-edged. But, it’s a very well-focused sound and at its best in the strophic songs which require a quiet concentration and where her attentiveness to the text enables her to express a range of changing emotions even while the music repeats.

‘Du liebst much nicht’ is perhaps a strange choice since there is no indication in Platen’s poem of the gender of the speaker or the object of their obsessive passion. Tandl’s steely vocal line captures the poet-speaker’s suppressed rage, and as the harmony takes unexpected twists and turns – like the desperate wringing of hands and heart – her intonation is very good, though the contrast between dotted and even groupings in the vocal line might be more differentiated. Kinsella is an expressive musician, and his playing suggests a vivid engagement with the songs’ emotions and dramas, but in this particular song, I find his rubatos a little too ‘free’ – it seems to me that, given the unalleviated, neurotic repetitions, bewailing unrequited desire, this is a song in which the metronome really should be ticking!

‘Des Mädchens Klage’ exists in three versions, and it’s the second lament that we hear, in which both performers convey a strong sense of penetrating suffering and anguish. A sequence of ‘Mignon songs’, and poems, follows, as Jacoby’s expressive recitations alternate with Schubert’s settings of Goethe. In ‘Kennst du das Land’, Tandl’s directness and clarity is a real asset, and complemented by Kinsella’s sensitive nuances. The voice sinks quite low in this transposition and needs more colour at the bottom of the stave, but Kinsella’s agility and energy inject dramatic intensity. ‘Heis mich nicht reiden’ (Do not bid me speak) is finely sung, the simplicity of the line nicely focused. There is a sense of moving forwards towards the optimism of the second stanza, when the sun drives away darkness of the night, and Tandl finds richer expressive colours in the rhetoric of the final stanza. ‘So lasst mich’ (Thus let me seem) is similarly characterised by clarity and directness, with effective expressive heightening – “Dann öffnet sich der frische Blick” (then my eyes shall open afresh). The duo are sensitive to the harmonic shifts, though occasionally I feel that the phrases need a bit more room to breathe.

‘Nur wer die Sehnsucht kennt’ (Only he who knows longing) sets passions aflame, while in ‘Der Jüngling an der Quelle’ (The youth by the stream) Tandl’s dreaminess is matched by the mood of ‘timelessness’ which Kinsella conjures. Tremulous tension and drama sweep through ‘Die junge Nonne’, the tautly sprung bass line, and the restless major/minor shifts, capturing the intensity of the young nun’s acceptance of death. We have both readings and sung renderings of Schiller’s ‘Thekla’ and Goethe’s ‘Der Fischer’. Schubert’s setting of the phantom voice of the doomed daughter of Wallenstein is a challenging sing, the vocal line tortuously confined and repetitive, and Tandl struggles a little to capture the otherworldliness of spirit’s questioning, but the mermaid’s pluck and insistence are neatly communicated in ‘Der Fischer’, the folky robustness of the melody well-negotiated, while Kinsella’s decorations and brief postlude are aptly wry.

After Jacoby’s reading of Klopstock’s ‘Das Rosenband’ we do not hear Schubert’s setting, moving instead from ‘rosy ribbons’ to wild roses. ‘Heidenröslein’ is another refrain song which Tandl interprets perceptively, the rising penultimate line of each stanza, “Röslein, Röslein, Röslein rot”, brimming with the youth’s possessive confidence and followed by the carelessness of his hunger for the “Röslein auf der Heiden” (wild rose in the heather).

Having returned to Goethe, Kinsella and Tandl remain in the poet’s company for the remaining few songs. Jacoby’s recitation of the final lines from Faust II precedes a quite melodramatic interpretation of ‘Der König in Thule’ – in which the dying king seems to fling his golden goblet into the sea with all his might and fury, rather than in pensive melancholy – and ‘Gretchen am Spinnrade’, in which the rigid relentlessness of the spinning wheel occasionally defeats Kinsella’s right-hand. Tandl works hard to build up the emotional desperation but, what with the wobbles of the wheel, this Gretchen can sound a little hysterical at times. More controlled, and fittingly ‘operatic’ is the final song, ‘Gretchen im Zwinger’ (Gretchen caged, also known as ‘Gretchens Bitte’ or ‘Gretchen’s prayer’) which Schubert left unfinished. Tandl and Kinsella perform the song as completed by Benjamin Britten in 1943, and it’s a fine conclusion to the disc, the rapidly changing textures and moods persuasively rendered.

This is an interesting disc which the Tandl and Kinsella have obviously enjoyed curating and performing, and which certainly conveys Schubert’s empathy with feminine experience. I’m reminded that in 1838, reviewing some newly published piano works by Schubert, Robert Schumann compared the composer to Beethoven, suggesting that Schubert was ‘ein Mädchencharakter’. There are twelve songs by Schubert setting female writers: I wonder if this Schubert’s Women invites a ‘sister-disc’, Schubert’s Poetesses?

Claire Seymour

Schubert’s Women

Klaudia Tandl (mezzo-soprano), Gabriele Jacoby (reader), Niall Kinsella (piano)

Gramola 99223 [66:30]

ABOVE: Klaudia Tandl