I Fagiolini’s third contribution to VOCES8’s Live from London series took its inspiration and its structure from T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, a poem described in the introductory programme note as having been ‘written 100 years ago in the wake of the catastrophic upheavals of the First World War and the ‘Spanish Flu’’.

The context of The Waste Land was, literally, the First World War, but Eliot’s true subject is not the human waste of bloodshed and conflict but the inherent sterility of Western man, which is not particular to time, place or circumstance. In the poem, past and present are in a continuous dialogue, as are East and West, myth and religion. The curse of the Fisher King’s land laid waste will only be relieved by the arrival of a mythic deliverer who can pass the ritual challenges posed. If the audience want to find connections between Eliot’s account of man’s search for the holy grail and modern plagues and vaccine task forces, then that seems not unreasonable at the present time. Eliot’s starting point is April, ‘the cruellest month’ (though Chaucer thought otherwise), ‘breeding/ Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing/Memory and desire, stirring/ Dull roots with spring rain. The ‘Order for the Burial of the Dead’ is the full title of the Anglican burial service, yet in burying the dead, man is also ‘sowing the seed’ of the next ‘crop’, as the buried are resurrected and reborn.

I Fagiolini began with the Tenebrae Responsories for Holy Saturday composed by Tomás Luis de Victoria, ‘O Vos Omnes’, which ‘chillingly [describe] a land wasted through intolerance’. Jeremiah’s Lamentation (12:1) expresses his identification with the city of Zion – what sorrow could be compared to hers, the Hebrew prophet asks – joining his sorrows with those of Christ. The vocal quartet – soprano Rebecca Lea, mezzo-soprano Martha McLorinan, tenor Matthew Long and bass Frederick Long – sang with dignified expression, the flowing melismas sombre but sweet. The whole motet was beautifully nuanced and coloured, each voice individualised, impressing the meaning of the text. The closing tierce de Picardie was a tender reminder of the paradoxes of life and death that Eliot’s poem interrogates.

William Byrd’s motet ‘Deus venerunt gentes’ from the 1589 Cantiones sacrae is also a sort of lamentation. It sets the first verse of Psalm 78 and weeps for the tragedy which has befallen Christ’s true Church: ‘O God, the heathen are fallen into thine heritage; thy holy temple have they defiled, and made Jerusalem an heap of stones.’ Greg Skidmore brought the vigour of baritone part to the fore and, with Frederick Long, provided buoyancy from which the higher voices could spring. Robert Hollingworth joined his ensemble. The tone was fresh and clean, and as the crisp contrapuntal entries accrued with increasing density there was a telling urgency.

Byrd’s setting was extended in a newly commissioned work by Ben Rowarth – one of four world premieres commissioned for this programme – which sets verses 2 and 3 of the Psalm. At the opening, sharp attack marked the upper voices’ sustained tones through which the men interjected speech-like fragments before cohering in dark but warm harmonies which made the beaming light of the women’s voices more striking still. The music pushed higher and harder, semitonal dissonances slipping in and out of focus; then came gradual diminishment, the long, sustained notes overlapping and diffusing into rebounding echoes and glissandi.

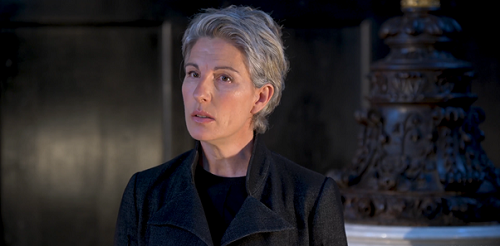

Tamsin Greig’s reading of Eliot’s multi-voiced poetry separated the two verses of Rowarth’s setting. Greig’s variation of tone, pace and dynamic was masterly. She both individualised the voices and made them cohere; in the words of Frost, the ‘sound is sense’, and this was reflected in the whispered choral echoes which at times shadowed Greig’s words.

Rebecca Lea’s high solo soprano, energised by clean intervallic leaps, initiated the concluding part of Rowarth’s composition. When the other joined her, vibrancy of texture and movement characterised the ensemble, occasional lulls growing from relaxation into the renewed strength of declamatory individual lines. Hollingworth subtly but surely guided his singers through the complexities, and as the voices were dispersed and silenced, Greig interposed the final part of Eliot ‘Burial of the Dead’, the misty image of the ‘Unreal City’ – ‘A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,/ I had not thought death had undone so many.’ – seeming in dialogue with the Psalm’s distress: ‘Their blood have they shed like water on every side of Jerusalem, and there was no man to bury them.’

Kenneth Leighton’s 1957 setting of Gerald Manley Hopkins’ ‘God’s grandeur’ was the prelude to Eliot’s ‘A Game of Chess’. The homophonic majesty of the opening statement evinced a cathedral-like certainty, yet there was nothing statuesque about this performance which responded to Leighton’s imagery with litheness and energy. Leighton depicts both faith and the questions which trouble it: ‘Generations have trod, have trod, have trod;/ And all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil’. The harmonies are challenging, and I Fagiolini’s precision and sure sense of direction were impressive. At the close, the fanfare-like gestures above held pedals fused splendour and poetry.

Greig’s skilful elucidation of the detailed layering of voices – Cleopatra, Ariel, Ophelia among many others – in ‘A Game of Chess’ was utterly absorbing. She made light work of Eliot’s artful syntax and complications, which sometimes seem needless and wilful, blending the elevated and the mundane. The transition from the carefree farewells of the London lasses, ‘Ta ta. Goonight. Goonight’, to Ophelia’s vulnerable farewell was wonderfully modulated and moving: ‘Good night, ladies, good night, sweet ladies, good night, good night.’ After Eliot’s fragmentation, the extended phrases of Victoria’s ‘Caligaverunt oculi mei’ seemed infinite and seamless. In the trio section, the three men (Greg Skidmore, Matthew Long and Frederick Long) brought intensity and depth to the familiar text: ‘O all ye that pass by this way, attend and see if there be any sorrow like unto my sorrow.’

In ‘The Fire Sermon’, Eliot’s allusiveness becomes still more dense and fragmented, and Greig’s quiet sobriety was well-judged. The images of urban decay, and the juxtaposition of suffering and prayer, of parody and sincerity, of death and sex, as well as the promise of the ‘violet hour’, found new form in Joanna Marsh’s setting of Pattiann Rogers’ poem, ‘Geocentric’:

Indecent, self-soiled, bilious

reek of turnip and toadstool

decay, dribbling the black oil

of wilted succulents, the brown

fester of rotting orchids,

in plain view, that stain

of stinkhorn down your front

[…]

forever the stench and stretch

and warm seeth of inevitable

putrefaction, nobody

loves you as I do.

Individual, angular recitation – noses wrinkled and brows furrowed, with the odd faux wretch – gave way to a playful jazziness, the voices ripping gleefully through ‘contagious ear wax’, and bristling Britten-esque text-setting enlivening the mix further. A twist of gospel piquantly flavoured the final line, ‘Nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen’ seeming to hover over the closing avowal, ‘nobody/ loves you as I do’. Sniffs and sneers were replaced with smiles.

‘Death by Water’ began with Vaughan Williams’ ‘Silence and Music’, which was composed in 1952 for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II and dedicated ‘to the memory of Charles Villiers Stanford and his Blue Bird’. Rebecca Lea was that soaring bird at the opening; when she was joined by Anna Crookes, they were ‘one voice’ entire. Calm bloomed into sonorous rapture: ‘the birds rejoice between the earth and sky’. This was magical. In Victoria’s ‘Ecce quomodo moritur’, from the Tenebrae Responsories for Holy Saturday, the despair of the opening – ‘Behold how the righteous man dies/ And no one understands’ – was transformed by the counterpoint of the final section into strength and conviction.

The waste land is a land of drought; water is needed to restore a sterile land to fertility. Shruthi Rajasekar’s ‘Ganga’s Peace’ eulogises the River Ganges, beginning with reverential humming and then opening up like a flower, in a heady mix of scent and colour: ‘O Mother Ganga Ma Mother feeds, purifies, nourishes us.’ There is tension, in the strained harmonies of the confession, ‘O Mother, your own children poison you’ but, as in Eliot’s poem, the rain breaks and the Thunder’s cry brings release. Eliot tells us:

‘Ganga was sunken, and the limp leaves

Waited for rain, while the black clouds

Gathered far distant, over Himavant.

The jungle crouched, humped in silence.

Then spoke the thunder

DA

Datta: what have we given?’

Rajasekar creates a mantra-like lesson, urging her listeners to ‘Control what you take’, ‘give back’, ‘be compassionate’. This was indeed wonderfully controlled singing, full of warmth and consolation, the final line, ‘shanti, shanti, shanti’, reminding us of Eliot’s peace that passeth all understanding.

To conclude, I Fagiolini returned to Manley Hopkins, by way of Joanna Marsh’s setting of John F. Deane’s ‘The World is Charged’, which takes its title from the first line of ‘God’s Grandeur’. Just as Manley Hopkins shows us how we are meant to look at the world, with eyes open and full of wonder, so Deane’s poem offers rich symbols which our imaginations can transform, leading to transcendence. For the first time (I think) in the Live from London series, screen subtitles were employed to help us enjoy and reflect upon Deane’s glorious chain of images: ‘the simultaneous long-tailed and spread-winged half-spectacular half-dive of the cock-pheasant’; ‘the Japanese anemone, pea-green heart within a scatter-ring of gold’; ‘ragwort, from there to woodlouse, eucalyptus, owl, and on to Sirius and the Plough …’ I Fagiolini plunged unreservedly into the harmonious glories of Marsh’s setting, conjuring a sense of openness, wonder and humility.

‘We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars,’ said Oscar Wilde. VOCES8 and their musical guests and collaborators have so inspired us during their Live from London series.

Claire Seymour

I Fagiolini: Anna Crookes, Rebecca Lea (soprano), Martha McLorinan (mezzo-soprano), Matthew Long (tenor), Greg Skidmore (baritone), Frederick Long (bass), Robert Hollingworth (director/countertenor), Tamsin Greig (reader)

The Waste Land Part 1, ‘The Burial of the Dead’: Tomás Luis de Victoria – (Tenebrae Responsories for Holy Saturday), Byrd – ‘Deus venerunt gentes’ (Psalm 78, v.1), Ben Rowarth – ‘Deus venerunt gentes’ (Psalm 78, vv.2 & 3, world premiere).

The Waste Land Part 2, ‘A Game of Chess’: Kenneth Leighton – ‘God’s Grandeur’, Tomás Luis de Victoria – ‘Caligaverunt oculi mei’ (Tenebrae Responsories for Good Friday)

The Waste Land, Part 3 – ‘The Fire Sermon’: Joanna Marsh – ‘Geocentric’ (world premiere)

The Waste Land, Part 4 – ‘Death by Water’: Vaughan Williams – ‘Silence and Music’), Tomás Luis de Victoria – ‘Ecce quomodo moritur’ (Tenebrae Responsories for Holy Saturday)

The Waste Land, Part 5 – ‘What the Thunder Said’: Shruthi Rajasekar – ‘Ganga’s Peace’ (world premiere), ‘What the Thunder Said’, Joanna Marsh – ‘The world is charged (world premiere)

VOCES8 Centre, City of London (live stream); Thursday 22nd April 2021.

ABOVE: I Fagiolini (Robert Hollingworth, centre)