Pierre Audi’s 2021 Aix Festival included two small pieces that continue the Festival’s operatic exploration of the larger Mediterranean world, meanwhile connecting the Festival’s general director to his Lebanese roots.

L’Apocalypse Arabe is a theatre piece conceived by Israeli Palestinian composer Samir Oder-Tamimi based on portions of Arab/American, Lebanese-born poetess Ethel Adnan’s 1980 eponymous poem (in French) about the 1975 Lebanese civil war.

The piece, an Aix Festival commission, was performed in the Grand Hall of Arles’s brand new Parc des Ateliers (re-purposed industrial buildings from the early 20th century envisioned as an “interdisciplinary creative campus” crowned by a Frank Gerry designed art museum). The campus opened on June 28, 2021, a project of Zurich’s ZUMA Foundation.

The production itself, conceived by Pierre Audi, was a joint effort of the Aix Festival and LUMA Arles that travels to the Abu Dhabi Festival. The interdisciplinarians were Mr. Audi as creator of the “mise en espace,” Urs Schônebaum who created the lighting that articulated the space, Chris Kondec who supplied extensive video, and Wojciech Dziedzic who created the costumes. All are celebrated (very famous) in their fields. May we say that the names on this interdisciplinary adventure were well positioned to challenge that of Frank Gehry in the opening salvos of LUMA Arles.

The central image of L’Apocalypse Arabe was the sun. It came in successive colors as both torturer and victim of the apocalypse, and as both destiny and fate. Seven voices interplayed in the action, that of the witness (the voice of the poetess who sees it all), the five voices of a sort of Greek chorus who offer neutral perspective, and the recorded spoken voice of an outsider who tries to understand what is happening.

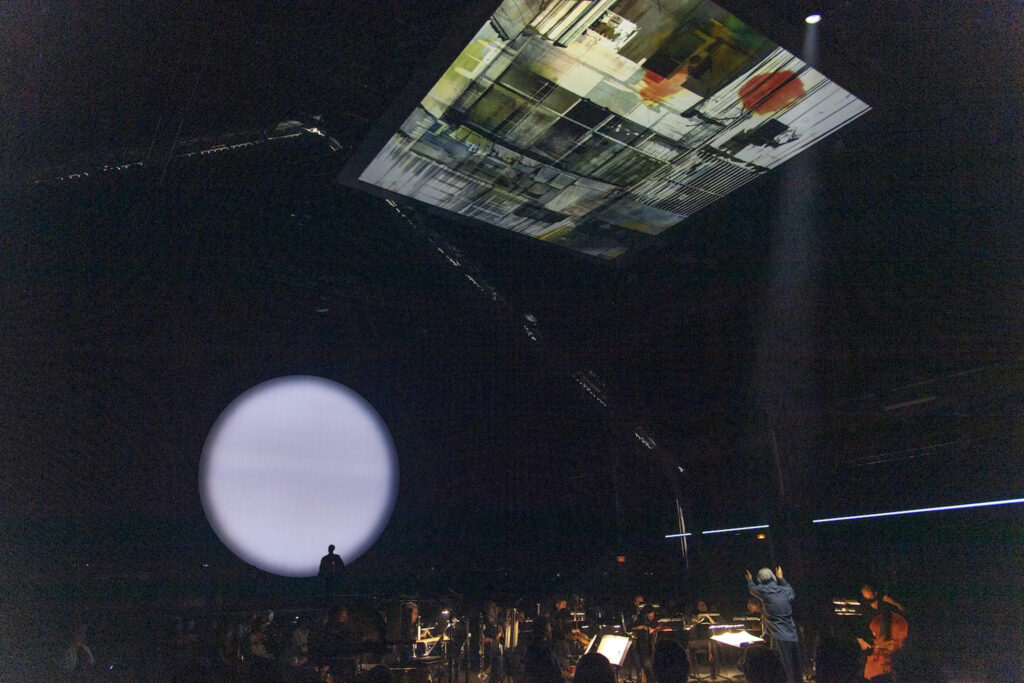

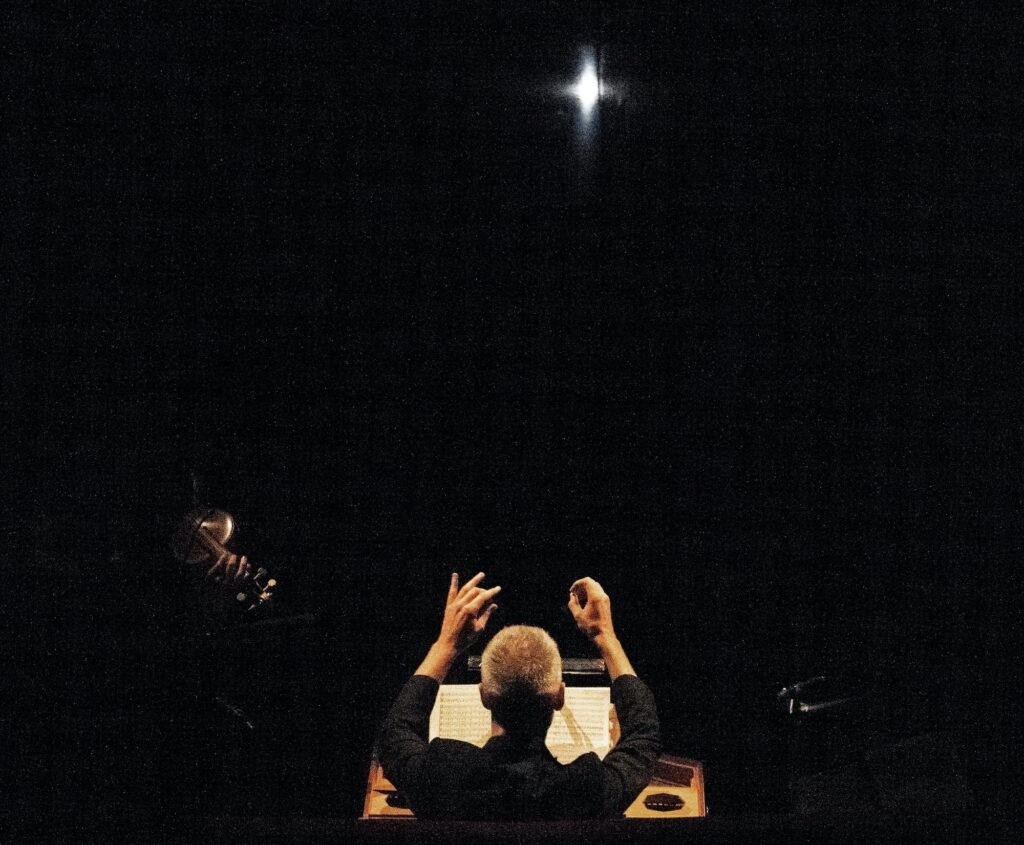

Mr. Oder-Tamimi’s orchestral score was performed by a 15 piece ensemble seated in the center of an immense space (western symphonic instruments — the composer is German schooled). The trombones blew tonelessly through their instruments, the horns repeated fantastical scales, the double bass struck his instrument, the strings scratched in a directed cacophony — splendid music of sonic excitement.

The witness, vividly rendered by Dutch baritone Thomas Oliemans (see lead photo), and the chorus both sing and chant and recite in mostly understandable French, but in some Greek as well. They move in circles around the orchestra, and around the periphery of the chairs (audience) encircling the orchestra. The Outsider broadcasts in spoken Arabic.

The text is highly poetic, a flow of images, metaphors and allusions, all quite complex, some very obscure, making it hard to perceive a comprehensible narrative movement within the poetic flow. A succession of solar colors, huge circular projections at two opposing poles, gave body to the poetic flow, arriving dramatically at a pure white sun. This image, made of light, underpinned by a flow of poetic heretical imagery created a real emotive wallop. And finally the two suns enacted the apocalypse in a lighting event, ever increasing to a super-intensity.

The temperature inside the Grand Hall was, shall we say, quite human — maybe 37 C (98.6 F). Humanely we were kept outside until minutes before the piece, prey to Arles’ famed mosquito hordes (depriving us as well of time to study the very thick program booklet). What price art?

Mise en scene: Pierre Audi; Decor/Lumiere: Urs Schönebaum; Costumes: Wojciech Dziedzic; Video: Chris Kondek; Musical director/Conductor: Ilan Volkov; The Chorus: Mille Allérat, Pauline Sikirdji, Fiona McGown, Camille Merckx, Helena Rasker; Le Temoin: Thomas Oliemans; Orchestra: Ensemble Modern. Grand Hall, Parc des Ateliers, Arles, France, July 5, 2021. Photos courtesy of Festival d’Aix-en-Provence 2021 © Ruth Walz.

Combattimento, la Théorie du Cygne Noir (Black Swan) was performed in Aix’s tiny, horseshoe, 1787 Théâtre du Jeu de Paume. It is based on the mortal combat of the knights Tancredi and Clorinda in Monteverdi’s madrigal version, then it mines the musical and emotional richness of early Baroque madrigals and monody. Tancredi’s inadvertent slaying of his beloved, Clorinda was a popular episode in Renaissance epics, portraying in very emotional terms a rare and unexpected catastrophe, and one of considerable consequence.

The Black Swan is a book (2007) by Lebanese/American Nassim Nicholas Taleb, a former option trader and risk analyst, now a hedge fund manager. The book explores randomness, probability and uncertainty, imploring the creation of “black swan robust” societies that can withstand unpredictable catastrophes.

The families of both Pierre Audi and Nassim Taleb fled Lebanon in its initial years of revolution, the 1970’s. Both men were then educated in France, Audi building his theater career in Britain, Taleb building his finance career in the U.S.

Swans are graceful white birds, thus a black swan is totally unexpected [though they do actually exist in Australia], but it may sail forth with the elegance of a white swan.

The quite unexpected juxtaposition of Black Swan theory with early Baroque vocal music is the brainchild of French early music conductor Sébastien Daucé and a Romeo Castelucci [a famous Italian avant-garde stage director] collaborator, Silvia Costa. The consequence was totally foreseeable — an hour and a half of rare and gorgeous vocal music supported by Mo. Daucé’s instrumental ensemble Correspondences overpowering a totally abstract and obscure theatrical language.

The narrative sequence of Combattimento, La Théorie du Cygne Noir is catastrophe, reaction, reconstitution, plus an epilogue. Its musical structure is the catastrophic moments of the Monteverdi Combattimento, then laments by composers Cavalli, Carissimi and Merula. The resurrection and reconstruction occurs in an oratorio by Luigi Rossi, and in arias and ariosos from operas by Cavalli, returning to the second part of Monteverdi’s famed madrigal from Book VIII, “Hor che’l ciel e la terra” as the epilogue, its tercets expounding new and healing perspectives to the extensive sufferings of the evening. Whew.

The small scale of the Théâtre du Jeu de Paume did not offer metteur en scène Silva the scope and technical resource to create more effective scenic choreography. She integrated her singers and scenic images into unified stage pictures, dividing her staging into three separate sections. The imagery of the first, the Combattimento, was the most effective in its abstractness, the more literal symbols of the lamentations and the reconstitution diminished the poetic world of the music.

Musically the evening was spectacular. Opportunities to hear live performances of early Baroque vocal music are very rare indeed, particularly performances by high level singer/actors. The madrigal repertory is incredibly rich in expressive tools, and extremely appealing in the richness of sound created by the integration of five and six voices. Mo. Daucé’s thirteen player Correspondences ensemble, utilizing a bevy of bowed, plucked, blown and struck instruments, enriched the vocal colors exponentially, eschewing more conservative approaches to period performance practice.

As is wanted in the madrigal world all voices were equal, though the world of monody (single voice arioso) individualizes the artists. The diversity of the chosen repertory allowed each of the singers to be within the single voice of the five or six voices of a madrigal, and also to be the solo voice of a monody. Two of the singers stood out, Italian tenor Valerio Contaldo, perhaps because he narrated Monteverdi’s famed monody madrigal, Combattimento, and French mezzo-soprano Lucile Richardot perhaps because she delivered Cavalli’s impressive Dido arioso “Alle ruine del mio regno,” later added a surprising counter-tenor vocal quality to the mix of voices.

Madrigal singers: Valerio Contaldo, Lucile Richardot, Julie Roset, Etienne Bazola, Nicholas Brooymans, Caroline Weynants, Antonin Rondepierre, Blanding de Sansal. Théâtre du Jeu de Paume, Aix-en-Provence, France, July 16, 2021. Combattimento photos courtesy of Festival d’Aix-en-Provence 2021 © Monika Rittershaus

Michael Milenski