There was no musical equivalent in Russia of the outpouring of Romantic lieder which occurred in Western Europe, as, inspired by the greatest poets of the day, song after song flowed from the pens of Schubert, Schumann, Brahms, Wolf and others. But, that does not mean that there was no Russian art-song. If Russian song belonged to the people, then the country’s composers drew upon the folk melodies and dances which expressed the suffering, yearning and the hopes of those vast masses, oppressed for so long. The resulting ‘romances’, frequently settings of the most popular poets of the day, were sung in decorous drawing-rooms, by families gathered around the piano. Often melancholy, perennially lyrical, that nineteenth-century Russian repertoire makes its presence felt during this recital disc by countertenor Hamish McLaren and pianist Matthew Jorysz, the programme of which ventures from the heights of Imperial Russia into rarely frequented terrain from the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

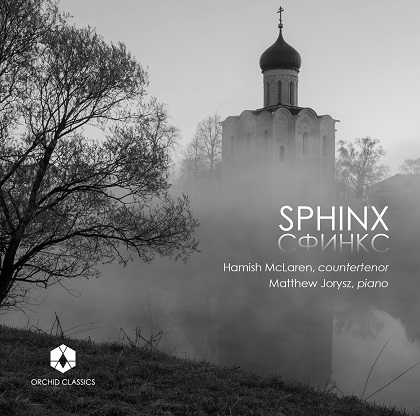

Indeed, the theme of Sphinx, recently released by Orchid Classics, is ‘distant lands’. This disc appears to be a personal labour of love for McLaren who, after studying History and Early Modern History at St. John’s College Cambridge where he was a choral scholar and lay clerk, undertook further study at the Royal Academy of Music where, taught Russian song by Ludmilla Andrew, he discovered the songs of, among others, Taneyev, Myaskovsky and Elena Firsova, whose music is celebrated here. Further musical archaeology during travels to St Petersburg, Moscow and Irkutsk in Sibera, in the summer of 2018, unearthed treasures such as two previously unrecorded film songs by Shostakovich, which feature on Sphinx.

Hearing McLaren perform in Hampstead Garden Opera’s 2019 production of Partenope, I described his countertenor as ‘strong and sweet-toned’, qualities that are much in evidence here.In fact, his tone is not just ‘sweet’ but very focused and distinctive, and his articulation of the Russian texts of these songs is idiomatically forthright, with the consonants making their mark. There’s a persuasive confidence and dramatic élan, from both McLaren and Jorysz, that underpins the flexible rhythms of Borodin’s well-known romance, ‘My songs are filled with poison’, and McLaren is assertive and accurate in negotiating the registral shifts and chromatic contortions of the vocal line, while maintaining a smooth, silky line. Complementing this brief intensity, ‘For the distant shores of your native country’ – which Borodin composed in 1881, when consumed with grief following the death of Mussorgsky – is more restrained, but no less profound of feeling. Pushkin’s poem tells of the poet-speaker’s separation from his beloved and of her plea that he should join her where the ‘vaulting heaven shines a deep blue’ – a phrase which allows McLaren to demonstrate his impressive registral range, as sorrow transmutes, briefly, to hope. Singer and pianist exploit the harmonic interest of the song, injecting interest into the declamatory vocal line and dark, pulsing quavers of the accompaniment, while conveying the overwhelming numbness of loss.

Sergei Taneyev, student of Tchaikovsky, teacher of Scriabin, Rachmaninoff, and Glière, serves as a bridge between Borodin’s nineteenth-century melodism and Sphinx’s twentieth-century repertoire. Jorysz, his touch crisp and clear no matter how deep he forages, enjoys the pictorial vigour of ‘A night in the Scottish Highlands’ and contributes much to the drama and architecture of the song, while McLaren evokes an almost ecstatic sense of wonder at the planets which burn in the night sky and the mesmerising music which heralds from a nearby castle. There’s more scene- and mood-painting in ‘Stalactites’, in which bitter tears drip from the frozen icicles, a melancholy, hypnotic fall of chilling suffering. Though sombre, McLaren’s vocal line incorporates telling nuance – of dynamics, colour and pulse – and warmth to balance the general funereal ambience. This is beautiful singing, somehow both tragic and uplifting, though at the close the finely tapered diminuendo creates a haunting echo of sobbing in the winter frosts.

There are two songs from Nikolai Myaskovsky’s Twelve Songs by Bal’mont, which set the words of the Symbolist poet, Konstantin Balmont. ‘The Albatross’ rocks with a gentle but haunting lilt, and McLaren captures the eeriness of the bird’s gliding trajectory, blossoming with the bliss of freedom, then subsiding into the calm satisfaction of solitude. The song which gives the disc its title is more lugubrious and Jorysz’s dotted rhythms acquire an accumulating burden of suffering, the toil of the slaves who ‘hammered and suffered endlessly’ to create the silent Sphynx which ‘reigns against the dark night’. McLaren’s description of this ‘enemy of conventional beauty’, ‘blind, mute and terrible’ sends a shiver down the spine.

Boris Tchaikovsky (1925-1996) studied with Shostakovich and is best known for his film scores. The two brief songs which form From Kipling were composed in 1994 and were intended to be part of a longer cycle. ‘Far Off Amazon’ is a toccata-like duet for voice and viola, leaning towards the austere, though here there is a touch of wryness as McLaren uses varied colours and weight to convey the yearning for elusive distant lands, while Nathalie Green-Buckley imbues the viola’s stuttering arpeggio with similar striving and desire. I feel that there’s more irony, though, to be wrought from the dry harmonics of ‘Homer’, which tells of a poet who tells old stories in a fashion sufficiently amusing to hoodwink listeners. Tchaikovsky’s Two Poems by Lermontov (1940) present the composer’s adolescent creativity and are more conventionally lyrical. McLaren enters fearlessly in ‘Autumn’, the purity of his tone capturing the spirit of the fifteen-year-old Tchaikovsky searching for his musical voice. ‘The Pine’ is more sophisticated and the harmonic and metrical shifting sands are beautifully sculpted.

Shostakovich’s Two Romances to Poems by Lermontov Op.84 are similarly tender, a wistful glance back to a Romantic past. McLaren communicates a wonderful vision of light breaking through the ‘night fog’ in ‘Morning in the Causasus’ – there’s a sense of promise and hope, which overflows in rich and sensuous imagery. This is an affecting rendition of a beautiful song. The narrative trajectory of ‘Ballad’, which tells of a maiden who urges a young man to dive into the abyss of the ocean to retrieve her necklace, is well-crafted and compelling, even as the tale unfolds morosely, the piano’s waves lapping lazily then dissipating tragically.

The Spanish Songs Op.100 (1956) are arrangements of Spanish melodies that Shostakovich was given by the contralto Zara Dolukhanova. Though it’s difficult to judge how genuine the composer’s commitment was to these songs, the melodies of which are accompanied by simple piano support, McLaren makes a convincing case for them. ‘Farewell, Granada!’ is full of emotive colours and vocal timbres, tempered by shadows of mourning, while ‘The Little Stars’ trips along with perky mischief. ‘The First Meeting’ is sincere and intense, erupting in fervent, almost wilful outbursts of remembered passion; Jorysz waltzes and dances lightly and spiritedly through the circumambulations of ‘Ronda’. The sweet wistfulness of ‘Dark-Eyed Girl’ drifts into the entrancing, empowering ‘magical dream’ of the Barcarolle (‘Dream’).

In 1950, Shostakovich was working on the film Belinsky (1950), in the first version of which a maiden performs the romance, ‘The Willow’. The scene was subsequently cut, and the song vanished, though it has been possible to establish that ‘The Willow’ was written to a free translation of the song sung by Shakespeare’s Desdemona by the Russian poet Ivan Kozlov (1779-1840). Shostakovich wrote of the song, ‘I composed this romance without posing myself the task of writing it in the style of old romances. I composed it as I would have had the notion to compose such a romance just popped into my head.’[1] ‘The Willow’ and the similarly discarded ‘A pointless gift, a chance gift’ have now been re-discovered, and it’s a gift to have these first recordings. The former has a touching archaic quality which McLaren exploits to the full, while not neglecting the tints of tragedy and the flowerings of memory; one can almost feel Desdemona’s beating heart, pulsing in Jorysz’s pained but passionate rhythm repetitions. The final image of the wreath-like green willow fades poignantly. ‘A pointless gift’, setting Pushkin, possesses a similar sincerity and focus; it’s easy to lose oneself in these beautiful performances.

Elena Firsova (b.1950) made the UK her home in 1991. Her Two Songs to Poems by Boris Pasternak are stark and direct. ‘The Wind’ is drawn from Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago and has a compelling simplicity; ‘Twilight’ is more subtle and delicately poetic. In the latter, McLaren sustains one’s attention through the declamatory delivery of the text, his countertenor crystalline but intense, while Jorysz shapes the poetic imagery with refinement. Another Pushkin setting, Firsova’s Winter Elegy Op.91 for countertenor and string trio, concludes Sphinx. Claudia Fuller (violin) and Ben Michaels (cello) join Green-Buckley in a performance which combines chamber-like interiority with quasi-operatic stature and depth.

Firsova pushes the voice high at the close, a final fraught gesture of the disc’s prevailing Russian pessimism and despair. Perhaps the melancholy of Sphinx is rather too unalleviated, but McLaren offers both those interested in Russian song, and those still to be beguiled, a rich feast.

Claire Seymour

Sphinx: Hamish McLaren (countertenor), Matthew Jorysz (piano), Nathalie Green-Buckley (viola), Claudia Fuller (violin), Ben Michaels (cello)

Boris Tchaikovsky – ‘The Distant Amazon’, ‘Homer’ (From Kipling); Shostakovich – Two Romances to Poems by Lermontov Op.84: ‘Morning in the Caucasus’, ‘Ballad’; Borodin – ‘My songs are full of poison’, ‘For the distant shores of your native country’; Taneyev – ‘A Night in the Scottish Highlands’ Op.33 No.1 (from Five Romances to poems by Y. Polonsky), ‘Stalactites’ Op.26 No.8 (from Ten Poems from Ellis’ Collection ‘Immortals’); Boris Tchaikovsky – Two Poems by Lermontov: ‘Autumn’, ‘The Pine’; Myaskovsky – The Albatross, Op.2 No.8* (from Twelve Songs by Bal’mont); Shostakovich – ‘Farewell, Granada!’, ‘The Little Stars’, ‘The First Meeting’, ‘Ronda’, ‘Dark-Eyed Girl’, ‘Dream’ (Barcarolle) (from Spanish Songs Op.100), Desdemona’s Romance* (Willow Song), A pointless gift, a chance gift*; Elena Firsova – Two Songs to Poems by Boris Pasternak: ‘The Wind’, ‘Twilight’*; Myaskovsky – ‘The Sphinx’ Op.2 No.11* (from Twelve Songs by Bal’mont); Elena Firsova – Winter Elegy* Op.91

* world premiere recording

Orchid Classics ORC100161 [76:31]

[1] Kirkman, Andrew. Contemplating Shostakovich: Life, Music and Film, Ivashkin, Alexander (ed.), Taylor & Francis Group, 2012.