This Signum Classics recording of a selection of Roxanna Panufnik’s chamber music, for varied vocal and instrumental forces, is titled Heartfelt – and it is indeed a generous programme, sincerely and warmly played by the Sacconi Quartet with soprano Mary Bevan, baritone Roderick Williams, pianist Charles Owen, oboist Nicholas Daniel, bassoonist Amy Harman and double bassist Andy Marshall. The music presented also exemplifies the diversity of Panufnik’s exploration of musical genres, cultures and contexts, a journey which on this disc takes her into inner worlds of stillness, both peaceful and dark.

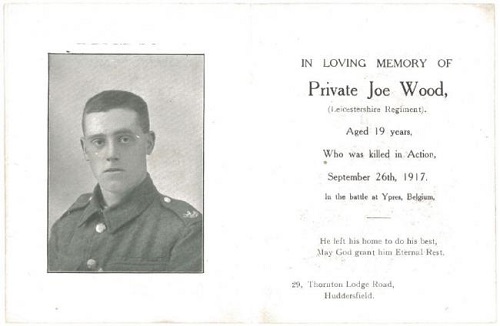

The disc opens with the longest work, the song-cycle for baritone and string quartet, Private Joe, which Panufnik composed in 2000 when the baritone Nigel Cliffe approached her with two letters that his great-uncle, Private Joe Wood, had written to his sister, Mary, and her husband, Tom, in 1917. The letters were sent six days apart, and three weeks before Joe’s death on 26th September at the Battle of Polygon Wood, Ypres. The first is affectionate and hopeful in tone, but evasive, “I hope you are both going on in good health, as I am quite well at this present time”; the second more urgent and strained, imploring somewhat insistently, “you know Mary we boys want looking after, as we are in France fight for you at Home”. These personal letters frame three other ‘letters home’, poems by Wilfred Owen (‘The Letter’) and Alex Waugh (‘From Albert to Bapaume’) being prefaced by a grimly ironic trench song, ‘And when I die’.

To paraphrase Owen, the Pity is in the Letters. The poet’s own letters from the front line are as shocking for their factual truthfulness as are his poems, and do not shy from reality. In November 1917, Owen wrote to his poet-cousin Leslie Gunston, ‘I think every poem and every figure of speech should be a matter of experience’, but Owen sought to convey not only his own personal experiences, but those of others. In ‘The Letter’ he juxtaposes mundanity and terror, through the voice of the generic ‘Tommy’, whose attempt to write a loving letter home to his “old girl”, sparing his wife the misery of his reality and maintaining an upbeat tone – “I think the war will end this year” – is interrupted first by jocular banter and irritated exchanges with his fellow privates, and then by the events of war that painfully undermine his deliberate fiction.

Roderick Williams brilliantly captures the different registers of Owen’s poem: the easy familiarity and slang of the soldiers’ camaraderie; the formality of the stilted ‘proper English’ with which the writer addresses his wife, the falsity of the platitudes emphasised by the cello’s rigid, stumbling pizzicato; the caring hopefulness of the plea, “Kiss Nell and Bert.” Panufnik recreates the sounds of the soldier’s present, the sul ponticello creak as a knife blade sharpens the broken pencil, the strings’ onomatopoeic screech as a shell explodes nearby, “VRACH!” – the latter made more painful by the preceding tenderness of the quiet repetition, “We’re out in rest now. Never fear.” When the fatal blow comes, time seems to stand still. Williams’ words fragment into disjointed syllables and sounds – “Guh! Christ! I’m hit.” – and the strings’ quite pulsing slowly fades. The tender note of the close is troubling, the whispered words, which Williams floats into nothingness, confirming the dying man’s affection for his wife and his comrade: “Write my old girl, Jim, there’s a dear.”

In ‘From Albert to Bapaume’, Panufnik matches the imagistic brevity and clarity with which Alex Waugh depicts a barren no-man’s land, a single, sustained string note, stark and pinched, supporting the observer’s vision of the ruined landscape, “Lonely and bare and desolate”. Unsettling glissandi recreate the distortion of the view seen by “dumb eyes” through a gas mask, “filtered green”. With laconic precision and expressive enunciation Williams records the shattered images of trench warfare: a tree “smutted and black”, a “solitary ruined house”, a “crumpled mass of rusty wire”. Denser, warmer string textures and the expansion and rising of the vocal line intensify the focus on the central image, “Long scattered ranks of poppies”, the only sign of life in this ravaged environment but one which brings painful human feeling into the numbed poem, as Williams’ beautiful head voice conveys the terrible loss that the wilderness embodies, “As though the blood of the dead men/ Had not been wholly washed away.”

The vaudevillian ‘And when I die’ screams into life with scooping scrapes from the upper strings above a jazzy bass, and is further enlivened by choric echoes of Williams’ gloopy, slurred tune and nasal vocal grimaces. The slower tempo of the second verse makes the defiant howling crescendo of the close all the more bitter and wild.

In the framing letters from Private Joe, Williams again conveys the false ‘formality’, “I have not had much time to write this last few days”, the baritone’s firmness of tone here contrasting with both the more relaxed salutation and farewell, and the upwellings of intensity as personal feelings surface – the tender, slightly tremulous repetitions of “little”, for example, when Joe wonders how often “my little girl comes to look at you”. William’s yearning lyricism is sweet but sad, “I want to know if she is doing as I asked her”, and he imbues strong feeling into simple details, such as a loved one’s name: “I want you to please give our sister Carrie a shilling or two.” The delicacy of the strings’ light ostinatos and oscillations creates a sense of distance, but also an innate restlessness, the beautiful softness laden with pathos.

There’s a weariness in Williams’ voice at the start of the final movement of the song-cycle, ‘Letter 2’, which is complemented by a tension that heightens the strings’ lyrical introduction. The vocal phrases, held up by textual repetitions, become increasingly agitated leading first to the openness and vulnerability of the admission, “I am completely done in now”, and then to the desperate request that Mary send a “nice sized Parcel”, the drawn-out admonition, “please”, and high sustained farewell, “Best Love to All at Home”, intimating mental fracture. What might have been kitsch, Panufnik and Williams make heart-breaking.

The other vocal item on the disc is ‘Second Home’ which began life in 2003 (rev. 2006) as a set of four variations for piano on a Polish folk theme, ‘Hejze ino! Fijołecku leśny’ (Hail, woodland violet!), expressing Panufnik’s feelings about the homeland of her father, the composer Sir Andrzej Panufnik. This version for piano quintet and soprano was commissioned in 2011 to mark Poland’s presidency of the EU, and its premiere also commemorated the 20th anniversary of Andrzej Panufnik’s death. Mary Bevan’s opening statement of the theme (in Polish dialect) is haunting and vivid, and when she is joined by pianist Charles Owen and the Sacconi Quartet the dissonant tints cast by the false relations capture the yearning of the violet, as yet untouched by the sun’s rays, to blossom and thrive.

The instrumental episodes have a stirring richness – the strings dig deep into the thick harmonies – that beautifully off-sets the crystalline shine of Bevan’s soprano; then, solo instruments come to the fore, the textures more spacious. The theme works itself into almost manic dance, chords pounding, fragments repeated, until the feverish energy suddenly dissipates, and Bevan reiterates the violet’s fervent but unsatisfied longing, “Where can I grow being so small?” The withdrawn, resigned acceptance, “I would be hidden by the pines and the shrubs!”, is a painfully honest close.

Of the instrumental works presented, two started life as solo string test pieces for string competitions. Hora Bessarabia invokes a gypsy spirit, exploring the highly ornamental doina and the spinning hora dances, and was composed for the 2016 Yehudi Menuhin Violin Competition. In this version for violin and double bass, Hannah Dawson and Andy Marshall enjoy a compelling musical conversation: the registral gap between the two instruments is vibrantly exploited and both musicians demonstrate agile expressiveness and virtuosity. At times introspective and improvisatory, elsewhere exuberant and raw – as when slapping pizzicati counter the bass’s heavy, accelerating tread, enticing the players to stamp their own feet – Hora Bessarabia is here given a very sincere, personal reading.

(c) Alejandro Tamagno

Canto for viola was composed for the Lionel Tertis Viola Competition in 2019 and is based upon an Ashkenazi Jewish chant ‘Y’hi rotzon’ (May it be Thy will). Robin Ashwell is an eloquent ‘cantor’, his tone searching at the bottom, reflective in the middle, and tensely ardent at the top. The double-stopping is beautifully smooth and sweet, harmonics sing with quiet melancholy, and the sweeping string-crossings as left-hand pizzicato gently pulse in the hinterland are mesmerising.

There is more ‘divine singing’ in Cantator and Amanda. Commissioned for the Rye Arts Festival 2011, the work draws upon the 14th-century Rye legend of a monk, Cantator, whose elopement with a local girl, Amanda, is thwarted, leading to Cantator being bricked up alive in the Friary walls for breaking his vow of chastity. The bassoon – played here with lyricism and poignancy by Amy Harman, evocatively accompanied by the Sacconi Quartet – sings Amanda’s song of heartbreak and death. The warmth of remembered love, the excitement of newly felt passion, restlessness and fear, pain and pathos unfold in a persuasively told tale.

We return to the epistolary theme with the oboe quintet Letters from Burma, commissioned in 2004 by the Summer Music Society of Dorset for the Vellinger String Quartet and Dougie Boyd (now artistic director of Garsington Opera). The eponymous letters were written by Aung San Suu Kyi to a Japanese newspaper between November 1995 and December 1996. Panufnik’s music is based upon a Burmese folksong which lauds the king, of the king, ‘Aung-ze Paing-ze’. Oboist Nicholas Daniel and the Sacconi Quartet again prove vivid storytellers, particularly in the second movement, ‘Young Birds Outside Cages’, which depicts the futile attempt of two children to touch their parents, the latter’s political convictions having seen them imprisoned. The tense pointed repetitions of the high strained high oboe, and the instrument’s plangent low flutterings, against the stillness of the strings’ full, held, intensifying chords, create a terrible stasis. The subsequent lyrical freedom of ‘Thazin’ is a welcome release, and the ‘Kintha Dance’ is rhythmically cathartic, though not lacking in dramatic conflict and protest.

The eponymous Heartfelt concludes the disc. It was commissioned by the Sacconi in 2019, at a time when the Quartet were experimenting with performances that combined sound, light and touch, collaborating with robotics designers Rusty Squid and interactive lighting designer Ziggy Jacobs-Wyburn in performances that aimed to enable audiences to enter ‘a space where the boundaries between performer and audience are dissolved’ and to ‘connect with a performer’s heartbeat through light and haptic technology’. It’s a sideways step, then, to Albie – a European Brown Bear based at Bristol Zoo’s Wild Place Project – whose anaesthetised heartbeat (prior to a medical procedure, and similar to that of a hibernating bear) is the starting point for ‘Lament for a Bulgarian dancing bear’, inspired by Witold Szabłowski’s harrowing book, Dancing bears. Panufnik again turns to folk music, here a Bulgarian melody which would be played on a gadulka, the timbre of which the Sacconi evoke by means of a leather mute and sul ponticello bowing. There is similar imitation of ethnic instruments in the first movement, ‘Uzbek Processional’, which also draws on the practice of 17th-century Uzbekistan court musicians to set the tempo of their performances according to their pulse.

Initially a tense aural recreation of an ICU monitor, the ‘Lament’ unfolds with soulful richness and absolute commitment from the Sacconi, the solo explorations powerfully affecting. The gradual infusion of dynamism and spirit, and gritty dissonance, as the bear awakens, is joyful. Heartfelt indeed.

Claire Seymour

Mary Bevan (soprano), Roderick Williams (baritone), Nicholas Daniel (oboe), Amy Harman (bassoon), Andy Marshall (double bass), Charles Owen (piano); Sacconi Quartet

Roxanna Panufnik: Private Joe, Canto, Letter from Burma, Hora Bessarabia, Cantator and Amanda, Second Home, Heartfelt

SIGCD673 [81:15]

ABOVE: Roderick Williams (image courtesy of Groves Artists)