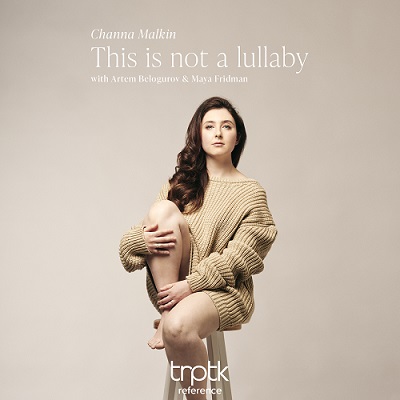

The Dutch soprano Channa Malkin explores aspects of motherhood and maternal love in This is not a lullaby, an album of songs by Mieczysław Weinberg, Sir John Tavener and her father Josef Malkin, which she released earlier this summer with the TRPTK record label. Her programme is a very personal one: “In the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, it [was] a blessing to work on this highly personal project inspired by my son Ezra. Becoming a mother has changed me in more ways than I can put into words.”

It seems to me, though, that Malkin’s programme – which she performs with pianist Artem Belogurov and cellist Maya Fridman – is as much about the past as it is about the present and future. The songs set texts in the Russian language (Malkin’s mother-tongue) by Gabriela Mistral, Anna Akhmatova and others, and allow the soprano to connect with and explore aspects of her Jewish-Eastern European cultural heritage, as expressed by the distinctly female voices of these poets.

The album’s title suggests that it is not concerned with archetypal tropes of mother love, and this is starkly apparent in the song-cycle which opens the disc, Rocking the child by the Polish-Soviet composer, Mieczysław Weinberg. This eleven-song sequence sets poems by the Chilean Nobel Laureate Lucila Godoy y Alcayaga, better known by her pseudonym Gabriela Mistral (1889-1957), selected from her 1924 collection Ternura (Tenderness) and translated into Russian. (David Fanning has supplied sensitive English translations.)

Mistral is often depicted as the ‘spiritual mother’ of Latin America, but while Ternura is entirely dedicated to children, the image of the mother in the poet’s work is an ambiguous one. These poems move beyond the icon of ‘the feminine’ and enter the emotional worlds of both mother and child, whose experiences are sometimes witnessed and imagined by a first-person poet-narrator. There is love but also anguish and alienation. The various voices are potent storytellers, speaking of bonds formed unbreakably, unexpectedly; of the sorrowful mother for whom “there is no path for sleep to come”; of the suffering of “children whose life was a torture” and “little feet, children’s feet … turning blue in the frost”; of the terror of separation, “I do not want my little girl ever to become a swallow”.

Presumably the narratives of displacement, fear and loss struck an emotional chord with Weinberg, whose own life was one of grief and exile. Having fled the Nazi occupation of Warsaw in 1939, during which his parents and sister were murdered, he was then forced to flee once again – from Minsk in Belarussia to Uzbekistan – when the Nazis invaded the USSR. Subsequently, he was invited to Moscow by Shostakovich, who had heard his First Symphony, and there he remained until his death in 1996.

The opening song of Rocking the Child, ‘The child was left alone’, introduces the rocking fifth which permeates the cycle, stable yet protean, bearing diverse sentiments. Here, as the piano softly echoes the voice, it seems to convey the simple innocence of the gentle face of a child, “trusting and reproachful”, waiting for its mother’s belated return home. The textures are sparse, highlighting the text, and Malkin’s soprano is pure and smooth but full of feeling. Throughout the cycle Artum Belogurov is a supportive, thoughtful partner, his touch light but never missing the opportunity for subtle suggestion. Here, the melodic expansion of the fifth to, first, a major sixth and then an octave – intimating the speaker’s joy as the child sleeps at her breast, lit by the benefaction of the moon’s rays – is darkened by the minor 9th which tints the piano’s octave falls, a hint of fear perhaps that the imminent return of the mother may break the enchantment of the moment.

In ‘And I am not alone’, the rocking fifth evokes the eternal bond of mother and child which counters the poem’s existential imagery of sky, moon and cosmic loneliness. Malkin’s open, direct vocal line is reassuring as it cleanly spans registers high and low. In ‘Rocking the cradle’, the motif is heard against the onomatopoeic swirling of the sea and wind, but the harmonic steadiness, despite slight major-minor inflexions, suggests that the mother will not be diverted from her lullaby. Indeed, the hubbub is stilled with the intense theopoetic declaration, “God rocks millions of universes quietly.” And, so the mother rocks her child.

Weinberg does at times indulge in sentimentalism, but Malkin’s understated delivery underscores the music’s essential beauty. In ‘Night’, the delicate vocal line evokes a magical twilight in which a dewdrop seems “a radiance” and a river’s sighs conjure the whole of life. With wonder the mother watches over her sleeping daughter, the soprano’s expressive lyricism fading tenderly at the close as the “tired earth fell to dreaming”. But there is vehemence too, as at the close of ‘A sorrowful mother’ when the restless repetitions of the piano’s frantic, fruitless ostinato circlings are overcome by a sudden, hot fierceness in the vocal melody: “I do not sleep, but my heart sleeps.” A similar closing flash of steeliness enriches the simple imagery of the rose, heavy with dew, which dominates ‘The dew’, revealing the strength of the mother’s conviction that “my daughter lived in my heart, always with me”. Here, we understand that it is not only the child who needs comfort and confirmation.

There is tremulous anxiety in ‘Fear’, a quiver of loss in the voice, as the mother dreads the natural growth that will tear her daughter from her. And, in ‘Little feet. Little hands’ there is urgency and bewilderment as the poet-speaker laments the world’s cruelty, the piano’s oscillating thirds, tripping rhythms and increasing unpredictability propelling the speaker’s ever more intense questions. Thunderous chords introduce the closing prayer, “Blessed be he that has given you to eat.” Countering the darkness, there is light, as in ‘Meekness’ where the perky folk song skips along breezily, chasing all the evil from the world.

Channa Malkin’s father, Josef Malkin, was born in Georgia in 1950, subsequently living in Moscow, Israel and in the Netherlands where he was for 25 years a violinist in the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra. His 2004 song-cycle Black Flowers marked a move to composition and has been followed by numerous instrumental chamber pieces, as well as songs in Dutch, Hebrew, English and Russian which have often been inspired by his daughter’s voice and premiered by her. Five Russian Songs sets texts by diverse poets on themes of childhood, parenthood and mortality. It was premiered in August 2020 at the Grachtenfestival and published recently as part of a larger collection of twelve songs. This is the world premiere recording.

‘A letter’, setting the Jewish-Crimean poet Ilya Selvinsky (1899-1968), is a delightful invitation into the rambling non-sequiturs of a five-year-old’s imagination, which leaps from affectionate avowals to alphabets, on to kisses and donuts, with infectious enthusiasm. The sweet clarity of Malkin’s soprano is heightened by a hint of mischief, one that is deepened during the deftly controlled acceleration to the rhythmic wriggles and wiggles of the close. The contemporary Amsterdam-based poet Vladimir Riabokon-Ribeaupierre (b.1957) wrote ‘To Polinka’ for his daughter when she was five years old. The text seduces the small child into the world of dreams with elusive images, rich and strange – “the walnut opened in half for you and for sleeping Anya”, the “vague expectations” of “the tale of the Fisherman and the Fish” – evoking a sea-change of day into night, from mundanity to mystery. The melody is comforting and sung with persuasive suggestiveness by Malkin, subtle use of vibrato and colour creating an enticing embrace.

‘Don’t leave me’ and ‘The Fortune Teller’ both set poems by the Soviet writer, Boris Ryzhy (1974-2001). In the former, the churning scales low on the piano keyboard are played with superb clarity by Belogurov, allowing Malkin to build effectively from mezzo piano lucidity – as the troubled poet-speakers pleads to be abandoned, left alone with his pain – to higher, frightening images of life as suffering – “a trivial burlesque” in which “Death [prepares] a poisoned bait” – the growing intensity and rootedness of which confirm their own irrefutability. Similarly, ‘The Fortune Teller’ is obsessed with the fateful struggle between life and death, and the guilt of survival. The piano hops and clangs, macabrely teasing and goading the poet-speaker who asks for his future to be revealed, finally dissolving into a futile circular motif as the speaker observes, “And the skies are turning red”. Ryzhy took his own life at the age of 26.

The sequence closes with a setting of the ‘Lullaby’ which Anna Akhmatova (1889-1966) wrote in 1915, in which a mother’s recounting of Tom Thumb’s adventures swiftly gives way to an existential anxiety about the ongoing world war and the fate of the children’s father. A prophecy of doom, “Troubles coming, troubles staying/ Troubles never wane”, is fused in the final stanza with a plea for salvation: “May Saint-George’s holy praying” spare their father pain. The dragging lilt of the song is ironic and dark, and a low, thudding portent throbs through Josef Malkin’s setting, denying the speaker’s eloquent imploring and the calm of the closing consonance.

This is certainly ‘not a lullaby’ but it is a fitting transition to the final work of the recital, Sir John Tavener’s Akhmatova Songs for soprano and cello. Though admitting that these songs are only tangentially connected to the central theme of motherhood, Malkin suggests that the poems and songs embody Akhmatova’s individual choice to follow a path quite different from that, mother and homemaker, expected of women during her day, and that she gave a voice to, and inspired, many women to have the confidence to make similar choices. Whatever, it’s good to have Tavener’s adroit musical interpretations of Akhmatova’s work included, not least because they provide the opportunity to hear cellist Maya Fridman’s beautiful tone and sensitive ‘singing’ in true partnership with the voice.

In the opening homage, ‘Dante’, both cellist and soprano immerse themselves in the Eastern European inflections and sorrowful lyricism. The song grows compellingly from quiet reflectiveness to fervent melodising, soaring to the stratosphere and then plunging low, neither registral extreme troubling Malkin who sings with impressive focus. The vocal line and the cello’s double-stopped slitherings blend beautifully in ‘Pushkin and Lermontov’ and again Malkin’s registral range and sheer power and presence are stunning. The song breaks off unexpectedly, but the unrest is settled by the cello’s childlike musings at the start of ‘Boris Pasternak’, which draw the voice closer to earth in simple but expressive ruminations.

It is a gruffer string voice that opens ‘Couplet’, quizzical, searching, restless. Despite its eloquence, this voice fails to console the troubled anxieties of the poet-speaker who tentatively, introspectively, questions the value of her own work, but the cello blossoms in the subsequent ‘The Muse’, drawing the soprano from its doubts to welcome art with lyricism both ecstatic and austere. The final song of death reprises earlier motives with sombre inevitability, the poet-speaker’s acknowledgement and acceptance of dislocation, displacement and departure finally quelling the restless glissandi, pizzicatos and vocal cries which represent human and artistic struggle.

This recital was recorded in December 2020 in the main hall of the Philharmonie Haarlem, an acoustic which showcases the quality of sound achieved by the TRPTK label which strives for ‘sonic immersion through perfect spatial and timbral fidelity using multichannel processes’. The disc is also neatly and stylishly presented in a three-panel vertical case which – alongside a booklet in which Malkin writes eloquently and engagingly about her choice of programme, and which contains texts and translations – is housed in a slip-case.

This is a disc which not only intrigues and satisfies, but one which promises much more to come. Malkin will undoubtedly create new projects which bring interesting repertoire, of personal significance and meaning, together in interesting and inspiring ways.

Claire Seymour

This is not a lullaby: Channa Malkin (soprano), Artem Belogurov (piano), Maya Fridman (cello)

Mieczysław Weinberg: Rocking the child Op.110 [I. The child was left alone II. And I am not alone III. Little feet, little hands IV. Rocking the cradle V. Night VI. A sorrowful mother VII. The dew VIII. Meekness IX. Fear X. A discovery XI. My song]; Josef Malkin: Five Russian Songs [I. A letter II. To Polinka III. Don’t leave me IV. The Fortune Teller V. Lullaby]; Sir John Tavener: Akhmatova Songs [I. Dante II. Pushkin and Lermontov III. Boris Pasternak IV. Couplet V. The Muse VI. Death]

TTK 0069 [57:00]