The mere mention of the word ‘crossover’ can be enough to raise the hackles of classical music lovers for whom the genre-splicer suggests not a genuine instinct for synchronous musical pulses but a diluted re-packaging in a search for new markets and profit.

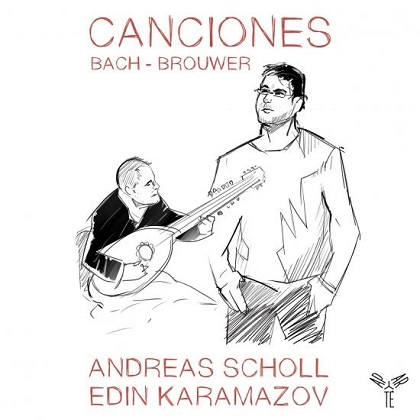

So, I was a little wary when approaching countertenor Andreas Scholl’s Canciones: Bach-Brouwer – a collaboration with lutenist and guitarist, Edin Karamazov, which places the music of J.S. Bach alongside the folk-creole-dance-European-inspired works of Cuban guitarist-composer-arranger Leo Brouwer. The publicity blurb describes the disc as one which ‘transports us between Havana, Leipzig, contemporary Cuba and baroque Germany’ – a bewildering blend, but perhaps also a canny bait to tempt the culturally curious?

I turned to José Anibal Campos’ rather florid liner note for elucidation of Canciones’ aims and ambitions, but, impassioned and well-informed as Campos’ ruminations undoubtedly are, I suspect something of the crossing over has got lost in translation. Alongside reflections on the ‘spiral’ – a ‘unison of disparate elements … rather like a kitchen whisk or blender … whose practical purpose is to bring together a host of ingredients and tastes in an ajiaco stew’ – Campos describes Brouwer, one of the ‘Cuban musical elite’ as a master of ‘stylistic fusions’, whose music mixes ‘classical, modernist, avant-garde and experimental traditions … strands drawn from Caribbean literature, chromatic colourings inspired by painting … as well as the rich world of African music and culture’. Each and every work by Brouwer, he declares, ‘serves as a breakdown of the artificial barriers of identity’.

Canciones begins with three English folksongs, a genre which Scholl’s 2001 disc, Wayfaring Stranger, explored. For Campos, these interpretations are a ‘magical metamorphosis of Johnny Cash being transformed into a variety of bard from Britain’s Victorian ear, the poetry of the Irishman Yeats in a 1960s rock concert … the words of the Scottish folk song The Water is Wide as interpreted by a composer from the Cuban Nueva Trova movement.’ My own assessment is rather more prosaic: Scholl sings the melodies with forthright vocal purity while Karamazov reshapes harmony and texture – a sort of Britten-esque reimagining, from a jazz perspective. There is no denying the unblemished, unaffected beauty of Scholl’s countertenor, and the English texts are impeccably delivered; but, there’s a strange ‘disembodied’ quality about these songs. Scholl’s angelic clarity lacks the ‘grain’ that is inherent in this music that speaks of lives lived within a community shaped by land and locale, and the vocal line and accompaniment seem discomfortingly disjunct.

‘I am a poor wayfaring stranger’ begins in icy cool mode, the flinty accompaniment picking out prickly octaves, and Karamazov evades and disrupts the easy folk phrasing of the voice; as Scholl’s melody becomes increasingly seamless and fluid in the final verse, so the accompaniment ventures onto spikier, sparser ground. The waywardness of the harmonic ‘bends’ seems at odds with the occasional stylised messa di voce which Scholl employs. A restless riff introduces ‘Down by the Salley Gardens’, until a low bass pedal anchors the song, but Scholl’s countertenor lacks the intimacy of a storyteller and though Karamazov’s nuanced harmonies invite the listener into the tale, the pressing quality of the vocal line – the uniform dynamic and fairly inflexible phrasing – inhibits such companionship.

I can’t hear ‘O Waly Waly’ without being transported back to Tokyo in the late 1990s, where each week I joined the Tokyo Madrigal Society – founded in 1929 by Keiichi Kurosawa, who had enjoyed singing madrigals while studying at Trinity College Cambridge in the 1920s, and whose son Hiroshi (known as Peter) continued his father’s tradition – in closing every rehearsal with a devoted rendition of this folksong, in honour of Pears and Britten who had sung it with the group when they visited Japan during in the mid-1950s. Here, Karamazov proffers a jazzy, jangling introduction which is promptly subdued by the entry of the voice, and though the subsequent re-harmonisations are of interest, I couldn’t be entirely persuaded by the duo’s folky foraging.

Campos describes Brouwer’s Canciones Amatorias – originally written, in 2004, for mixed a cappella choir and arranged subsequently by the composer for voice and guitar – as a ‘minimalist history of the song-writing tradition’, a history which evokes ‘remembrances of troubadours and minstrels … aromas of the Gauchesco tradition’ fused with the Song of Songs and ‘Lorcan echoes’. A panoply of perfumes in this potpourri, then. And, as affectionately presented by Scholl and Karamazov, these three love lyrics are indeed beautiful, sensuous and sonorous. ‘Yo he de enseñarte el camino’ (Come love, I must point out the path to you) is spacious and free: the twitches and tumbles of Karamazov’s guitar make it feel as if a spring coil is about to burst its bounds, and, by means of his artistry, he is just about holding the passion in check. I’m put in mind of an Elizabethan sonnet in which spiritual transcendence and physical consummation are united in the figure of the elevated beloved, and when Scholl rejoicingly appeals, “Ven Amor!”, the wonder and elation bring to mind the spirit of Britten’s first Canticle.

The metrical asymmetry of ‘El Cantar de los Cantares’ conjures a delightful impetuousness and joy. Playful explosions in the guitar sound ecstatic and breathless, yet Scholl calms the angularity of the vocal line into smooth sweetness. This is music to listen to with the light off and the perfumed candles burning. Innocence and experience seem to converse, and the final melismatic vocal wandering evokes realms that are both physically palpable and spiritually lofty. ‘Balada de un día de Julio’ is thrillingly intense but closes with a wonderful sense of freedom and release.

The duo also present some familiar Baroque fare. In Gottfried Heinrich Stölzel’s ‘Bist du bei mir’ (which, found in the 1725 Anna Magdalena Bach notebook, was initially attributed to J.S. Bach) Scholl somehow combines plushness with purity, though I miss the velvety warmth of an organ, or continuo, accompaniment. The calm faith of Bach’s harmonisation of Johann Crüger’s chorale melody, ‘Brunnquell aller Güter’, is compelling while ‘Jesus bleibet meine Freude’ embraces one in an oral comfort-blanket.

Karamazov performs some solo items, too. An Idea: Passacaglia for Eli, whichwas written in 1999 for the 75th birthday of Eli Kassner, has a Bach-like clarity with implied voicing and counterpoint that is utterly persuasive; the arrangement for guitar of the Cello Suite No.1 in G major BWV 1007, less so. Karamazov’s expressive performance communicates a deep personal response, but I find the bassy reverberation and the harmonic ‘filling-in’ destroys something of the magic of the implied and imagined, but unheard, counterpoint that the cello player is required to infer through the voicing of the solo lines, grading of dynamics and conversational phrasing.

Moreover, each of the dances in the suite has its own formal character, and social rectitude, something which Karamazov’s elaborations and freedoms do not always maintain. The ornamentations are tasteful but something of the spatial clarity of the architecture is lost. The vigour and echoey restlessness of the Courante is a little too ‘wild’ for my liking, but the lovely simplicity of the ‘Sarabande’ evokes the sincerity and sentiment of a seventeenth-century chanson. The ornaments in the two Minuets do serve to complement and enhance the character of the dance, and I love the way that in the second Minuet the lightness of the da capo repeat cleanses the palate before the infectious rush of joy in the Gigue.

Brouwer’s ‘Omaggio a Szymanowski’ from the 2001 Nuevos Estudios Sencillos (New Simple Studies) closes the disc. Karamazov’s cantabile melody, resting tenderly on the deep bass syncopations, has a lovely lyrical wistfulness. “The water is wide, I can’t cross o’er”, laments the singer at the opening of ‘Waly, waly’, but in Canciones: Bach-Brouwer, Scholl and Karamazov do at times have “wings to fly”, bridging the divide between diverse musical shores.

Claire Seymour

Canciones: Bach-Brouwer

Andreas Scholl (countertenor), Edin Karamazov (lute, guitar)

Brouwer – English Folk Songs (‘I am a poor wayfaring stranger’, ‘Down by the Salley Gardens’, ‘O Waly Waly’); An Idea. Passacaglia for Eli; Canciones Amatorias (‘Yo he de enseñarte el camino’, ‘El Cantar de los Cantares’, ‘Balada de un día de Julio’; J.S. Bach – Cello suite No.1 in G major BWV 1007; Gottfried Heinrich Stölzel – ‘Bist du bei mir’ (Diomedes oder die triumphierende Unschuld); J.S. Bach – ‘Brunnquell aller Güter’ BWV 445, ‘Jesus bleibet meine Freude’ BWV 147; Brouwer –‘Omaggio a Szymanowski’(Nuevos Estudios Sencillos).

Aparte AP263 [54:09]