The fifth revival of Jonathan Miller’s well worn-in production of Bohéme has brought with it a number of revelations. On the first night (February 3), it was the conducting of Ben Glassberg: lithe of tempo (particularly in the opening scene), packed with detail, blessed with intelligent, non-indulgent rubato, plus a masterful change of mood and pace in the final act. Come this matinée performance, all of that is intact, but there were significant cast changes that changed the ‘flavour’ of the performance significantly.

The most significant alteration was the Mimì, from Sinéad Campbell-Wallace to Nadine Benjamin. There were two major benefits to the change: chemistry between Mimì and David Junghoon Kim’s Rodolfo, previously near-absent, was now palpable; and Benjamin’s voice itself is to die for. Her soprano has a burnished, velvety tone that works perfectly; she has a developed lower register that finds her easily essaying the registral extremes of Mimì’s part. The sense of real attraction and rapport between Benjamin’s Mimì and Kim’s Rodolfo allowed the final scenes of the opera to tear us apart emotionally (as indeed they should). It is an almost complete assumption of Mimì, and the cheers at her curtain call were fully deserved. The final piece in the jigsaw will be Benjamin just elevating her acting skills so that she is fully in the role – occasionally, gestures felt a little learned, a touch studied. Benjamin sang Musetta in the 2018 revival at the Coliseum (under conductor Alexander Joel). It was in 2018, too, that Benjamin triumphed in the role of Ermyntrude in the UK premiere of Mascagni’s Isabeau at Opera Holland Park and first came under my radar; this just confirmed how special she is: Benjamin has the ability to deliver Puccini’s lighter passages superbly, and yet can easily sustain a long cantabile. Her death scene was the most touching since Mary Plazas took on the role here at ENO some decades ago now.

The other change in cast was perhaps not as fortuitous: the role of Musetta shifted from Louise Alder to Elin Pritchard. Alder had been enchanting, feisty and funny, and vocally impeccable; Pritchard was less of all of these, despite a voice that is self-evidently huge. It was hard to enter into Musetta’s character: there were some significant vocal swoops from Pritchard, and in this performance, it was between Musetta and Marcello that the chemistry was largely absent. A shame, as in Charles Rice we find a fine Marcello with strong voice and powerful stage presence. Pritchard will return to ENO as Ofglen in the upcoming run of Ruders’ The Handmaid’s Tale in April.

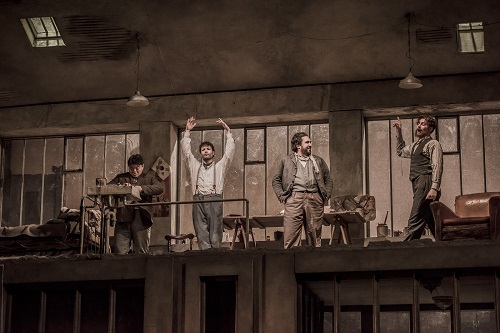

Miller’s production is very much a known quantity, displacing Puccini’s Paris to the early 1930s, with sets influenced by the likes of Henri Cartier-Bresson, Kertész and, particularly, Brassaï. Rotating sets (activated by stagehands) allow for smooth transitions, giving a sense of flow to the performance. The garret has a subsidiary room (where characters can retreat to) and a flight of stairs, allowing the audience to see more of exits (the lads on the way to the Café Momus, for example) and entrances (Mimì). Jean Kalman’s lighting, under revival lighting designer Martin Doone expertly sits on the knife edge between emphasising the squalor of the garret and its environs, and allowing for the celebration of poverty. The garret is also a blank canvas for emotions, from the tomfoolery of the opening scene to the death of the last.

The first scene, which finds the ‘lads’ (Rodolfo, Marcello, Colline and Schaunard) in riotous, playful form, felt somewhat muted, certainly in comparison with the first night and despite Glassberg’s breezy tempo. It was perhaps left to the Benoit of Simon Butteriss to set the scene fully alight; a fabulous, funny assumption of the role that sits somewhere between Alf Garnett and George Roper. Immediately, the performance rose a level with the vocal entrance of Mimì, perhaps taking her Rodolfo with her; Kim’s ‘O soave fanciulla’ (here, ‘O you vision of beauty’) was far more on track. It is good to see Kim in a major role, having worked his way through a string of minor roles at Covent Garden. Both Benson Wilson’s Schaunard and William Thomas’ Colline were well-taken; perhaps a touch more character to the ‘Coat aria’ would have sealed the deal from Thomas.

The children’s chorus (wearing masks for covid reasons) was on fire – even more so than on the first night, and the second act was certainly the liveliest. The third act is the examination of the two couples’ dynamics (Mimì/Rodolfo; Musetta/Marcello) and puts all of these singers under a microscope, and it was here that Benjamin and Kim really came into their own.

Whereas on the first night the strength of the performance was very much that of a company effort, this mid-run Bohème matinée was memorable above all for the Mimì of Nadine Benjamin. May she return soon.

Colin Clarke

Mimì – Nadine Benjamin, Rodolfo – David Junghoon Kim; Marcello – Charles Rice, Colline – William Thomas, Schaunard – Benson Wilson, Benoit/Alcindoro – Simon Butteriss, Musetta – Elin Pritchard, Parpignol – Adam Sullivan, Policeman – Paul Sheehan, Official – Andrew Tinkler; Director – Jonathan Miller, Conductor – Ben Glassberg, Revival Director – Crispin Lord, Designer – Isabella Bywater, Lighting designer – Jean Kalman, Revival Lighting designer – Martin Doone, Children of Cardinal Vaughan Children’s Chorus (featuring singers from The Grey Coat Hospital); Children’s Chorus Director – Scott Price; English National Opera Chorus & Orchestra (Chorus master, Mark Biggins)

London Coliseum, London; Saturday 19th February 2022.

ABOVE: ENO La bohème © Genevieve Girling