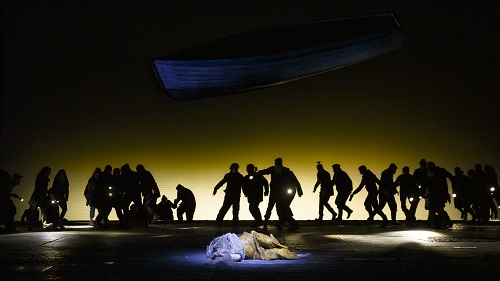

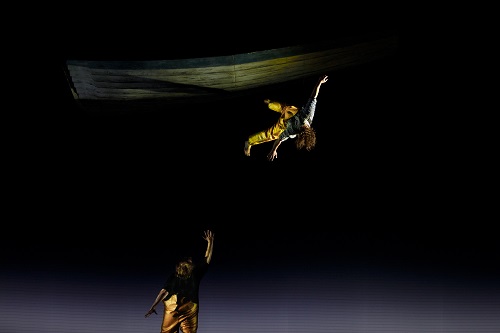

“What harbour shelters peace, away from tidal waves, away from storms?” The opening moments of Deborah Warner’s new production of Britten’s Peter Grimes at the Royal Opera House make it clear that there is no such harbour … only the bottom of the ocean. Grimes literally rolls onto the sloping stage of Michael Levine’s bare, black set, as if spat out by a breaking wave. Wrapped in his fishing nets, he flinches and flails. Above hangs a scuppered boat. “Will you step into the box,” commands Swallow, but we’re not inside a crowded Moot Hall, waiting for the coroner’s inquest into the death of Peter Grimes’s first apprentice to begin. This is a courtroom of the mind, and the Borough posse that moves across the stage – a black, amorphous mass, their caustic torchlights cutting viciously through the darkness – is swarming through Grimes’s own conscience, his guilt embodied by the aerial figure (Jamie Higgins) in yellow oilskins floundering above him.

It’s a striking approach to the Prologue, one which signals that this production is going to take us deep into Grimes’s psyche. But, Warner juxtaposes this subterranean dreamscape with a suburban deprivation which is all too real, and disturbing. George Crabbe’s ‘The Borough’ (1810) describes a dilapidated port-town, where in ‘half-buried buildings next the beach,/ Where hang at open doors the net and cork … squalid sea-dames mend the meshy work/ Till comes the hour when fishing through the tide the weary husband throws his freight aside;/ A living mass which now demands the wife,/ Th’ alternate labours of their humble life.’ Warner finds a modern-day parallel for this poverty and wretchedness, updating the action to a post-Brexit coastal town where impoverishment and lack of opportunity have bred despair, disgruntlement and distrust. It’s a dingy portrait of urban decay – run-down, refuge-strewn and resentful.

The toxic landscape pollutes lives and minds. Restless with right-wing indignation, the community, a feral pack, have taken back control and they mean to keep their borders closed. There’s no room for ‘difference’ in this dystopia-on-sea. The crowd scenes are both thrilling and terrifying. Warner creates a cohesive collective – brilliantly choreographed by Kim Brandstrup – and while she individualises each member of the ROH Chorus, they sing with one voice, and their song is violent. Oddly, though, while the flashpoints of conflict spiral savagely out of control, they don’t have a particularly strong dramatic momentum: the violence feels rather static, perhaps reflecting the community’s own impotence. The pub round, ‘Old Joe has gone fishing’, which the revellers sing to banish the threat of both the storm and Grimes’s visionary song, releases a previously pent-up vigour, but the whole scene feels rather claustrophobic, as the stained wall-paper of the back wall stretches the whole length of the set and significantly foreshortens the stage, crushing cast and Chorus close together.

But, while this crowd never give the impression of physically advancing on Grimes’s hut, it’s impossible not to be shocked by the explosion of aggression that culminates in their chilling cries, “Peter Grimes!”, as bare-chested neo-Nazi thugs slam an effigy into the ground. I was reminded of Crabbe’s description of the morally deformed Peter Grimes himself: ‘The mind here exhibited is one untouched by pity, unstung by remorse, and uncorrected by shame; yet is this hardihood of temper and spirit broken by want, disease, solitude, and disappointment.’

Warner’s naturalism isn’t entirely convincing, though. It’s not just the anachronisms. Workhouses, prepubescent apprentices and the horse and cart are not familiar features of twenty-first-century life. Nor, for that matter, is Sunday morning church-going, and it’s hard to imagine which members of the sleazy community we’ve witnessed in the pub are singing the off-stage hymn that interweaves through Ellen’s conversation with Grimes’s second apprentice. What most troubled me, though, was that the force which drives both Crabbe’s poem and Britten’s opera seems to me to be missing, or at least weakened. That is, Britten explained that having lived all his life ‘closely in touch with the sea’ he wanted to express ‘my awareness of the perpetual struggle of men and women whose livelihood depends on the sea’. Levine scatters the set with broken nets and coils of rope, but it’s a long time since the livelihood of anyone in seaside towns such as Margate and Jaywick Sands depended on the sea. I had the misfortune to spend my teenage years in one such town: there weren’t many fishermen then, and there certainly aren’t now. Peter Grimes’s own hyperactive pallet-shifting, rope-coiling and cone-switching in the opening Act seem rather out of place.

Also, other than during the underwater dream-scenes the threat of the sea itself isn’t strongly felt in this production. Grimes’s dilapidated hut (damaged by the storm, I presume) doesn’t seem to be perched on the top of a cliff: the apprentice climbs the ladder which lays across the steeply raked set to make his way out, and the landslide, which is the cause of the boy’s fall, seems to have fallen into the hut. That said, Peter Mumford, who lights the opera with imagination and penetration, does create a wonderful fusion of sea and sky – grey, tremulous, evoking the flicker of waves and sunlight, simultaneously bleak and beautiful. Anyone who has stood on Aldeburgh beach early on a chilly February morning will recognise the grandeur and power of this image.

The ROH Orchestra play wonderfully as always, and Sir Mark Elder sculpts gloriously well-defined lines and colours. I wish that Warner had ‘used’ the instrumental interludes, though. Dropping the front curtain and adorning it with Brechtian tags, ‘Interlude 2’ etc., feels like a cop out when these orchestral narratives are so embedded in the drama.

The cast are superb. I found Bryn Terfel’s Balstrode rather too forceful in the opening scenes, but as the opera progresses his role within the community is clearly drawn and his relationship with Peter sincere. Jacques Imbrailo oozes unscrupulousness as the wheeler-drug dealer spiv, Ned Keene, his nylon football shirts as shiny as his grin. John Graham-Hall is terrific as the pugnacious Methodist Bob Boles and is mercilessly egged on by Auntie’s two Nieces, Jennifer France and Alexandra Lowe, who give well-judged performances. Auntie herself is presented sympathetically by Catherine Wyn-Rogers, while Rosie Aldridge makes clear just how dangerously noxious the drug-addled Mrs Sedley really is. James Gilchrist is a niminy-piminy Reverend Horace Adams and Stephen Richardson a fine Hobson. John Tomlinson’s Swallow is a little too arch at times.

Maria Bengtsson has a beautifully crystalline soprano, but it’s a little light for the role of Ellen Orford. She does, however, impressively convey Ellen’s redemptive role. And, ‘Glitter of waves’ really does shine and, for a moment, “lift our hearts on high”. In this scene, Bengtsson and the apprentice form a persuasive bond, and in the latter, silent role young Cruz Fitz displays a variety and range of expression far beyond his years, suggesting that while young John is afraid of the storm within Grimes, he is not afraid of, and even feels some pity for, the alienated fisherman himself.

Britten’s Grimes is, of course, very different to Crabbe’s abusive psychopath who relishes inflicting both physical and psychological torment on his young apprentice, who ‘sobb’d and hid his piteous face; – while he,/ The savage master, grinn’d in horrid glee:/ He’d now the power he ever loved to show,/ A feeling being subject to his blow.’ In 1946, Peter Pears described the operatic Grimes as ‘considerably removed from the desperado of the poem’: ‘Grimes is not a hero nor is he an operatic villain. He is not a sadist nor a demonic character, and the music quite clearly shows that.’ Allan Clayton sings Grimes’s visionary arias with gorgeous lyricism. ‘The Great Bear and Pleiades’, which is sung to the pub door as Grimes turns away and retreats from the astonished and alarmed Borough pub-goers, is especially affecting: Clayton’s tenor is easeful in the high-lying passages, and controlled and strong as it descends, “Who can turn skies back and begin again?” But, there is a darkness within Britten’s Grimes which, though his singing is incredibly nuanced, Clayton prefers, vocally, to leave in the shadows, complementing the withdrawal by Grimes into the isolation of his own psychological torment which is emphasised in this production.

And, so, in the ‘mad scene’ this Grimes slumps to the floor and leans against the wall. In Crabbe’s poem, in his madness, the landscape becomes Grimes’s reality: cast out from the community, ‘Peter chose from man to hide,/ There hang his head, and view the lazy tide/ In its hot slimy channel slowly glide’. Here, though the sea does not feel very present, as the tuba sighs its mournful semitone Grimes sinks into the ocean’s embrace, and we slip underwater with him, then watch as a body – Grimes? His apprentice? – comes to rest. On the bottom of the sea-bed? Or on the shingled shore? We don’t know and it doesn’t matter. In the words of Crabbe, echoed by Montagu Slater at the close of the libretto, there is only one certainty:

‘With ceaseless motion comes and goes the tide

Flowing, it fills the channel vast and wide;

Then back to sea, with strong majestic sweep

It rolls, in ebb yet terrible and deep.’

Claire Seymour

Benjamin Britten: Peter Grimes

Hobson – Stephen Richardson, Swallow – Sir John Tomlinson, Peter Grimes – Allan Clayton, Ned Keene – Jacque Imbrailo, Rev. Horace Adams – James Gilchrist, Bob Boles – John Graham-Hall, Auntie – Catherine Wyn-Rogers, First Niece – Jennifer France, Second Niece – Alexandra Lowe, Mrs Sedley – Rosie Aldridge, Ellen Orford – Maria Bengtsson, Captain Balstrode – Sir Bryn Terfel, The Boy – Cruz Fitz, Aerialist – Jamie Higgins; Director – Deborah Warner, Conductor – Sir Mark Elder, Set designs – Michael Levine, Costumes – Luis F. Carvalho, Lighting design – Peter Mumford, Choreography – Kim Brandstrup, Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal Opera House.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Thursday 17th March 2022.

ABOVE: Cruz Fitz (The Boy) and Allan Clayton (Peter Grimes) © ROH/ Yasuko Kageyama