One might say of Daniel Slater’s production of Handel’s Tamerlano at The Grange Festival that the staging offers nothing about which to complain and that the singing gives much to praise and relish.

First performed in London in 1724, sandwiched between two notable successes, Giulio Cesare and Rodelinda, Tamerlano is perhaps Handel’s darkest opera. Sombre, claustrophobic, concerned with internal conflicts between love and honour, it moves inexorably towards its inevitable climax, with no distracting sub-plots and scarcely an unnecessary scene. The characters – Tamerlano, his defeated enemy Bajazet, the latter’s daughter Asteria, and the Greek prince Andronico who is both Tamerlano’s ally and Asteria’s lover – are tied together in a knot which gets tighter and tighter until it explodes, fractured by a noble suicide, the emotional wounds then repaired by repentance and release.

Robert Innes Hopkins’ designs do a good job in creating an enclosed world, guarded by pistol-pointing patrols, in which the eponymous tyrant incarcerates, torments and manipulates his enemies, while simultaneously trapped within his own emotional solipsism. The dress is modern but the motifs are antique and gently oriental, and sensitively lit by Johanna Town. We begin by peering through the ornate grille of Bajazet’s cell, then scene by scene through the first two Acts the layers are peeled away – neatly suggesting a Baroque theatre – as we move deeper into Tamerlano’s palace, arriving finally in the throne room where he plans to wed Asteria, the diagonal slants of the stage now meeting at a point before the flower-bedecked altar. The brightness of the white and gold of that scene is snuffed out by Tamerlano’s fury and vengeance in the final Act, in which the maze-ceiling slants and sinks low, and light is extinguished.

One would hesitate to say this was a ‘stand and deliver’ production, not least because the singing is so expressive and beguiling. But there was indeed a lot of standing about, not least from characters listening to another’s lengthy orations of emotion. There was also much ‘delivering’ to the audience, too, sometimes at the expense of dramatic intensity, as when Sophie Bevan’s Asteria, moved by the outrage of her father and beloved at her apparent betrayal, changes her mind about matrimony and reveals to Tamerlano her wedding-night assassination plot, delivering her furious diatribe to the audience rather than to her oppressor.

There’s so little directorial intervention that what few such gestures there are stick in the mind: the ‘boxing match’ duet for Tamerlano and Andronico – cleverly suggesting both their rivalry and their bonding – and the indication of a change of location when a character exits via one set of stairs and returns down an adjacent flight. It’s ironic that when Slater does impose some ‘humour’ on proceedings via some shenanigans with an airport security scanner, it distracts from some crucial plotting as Andronico instructs Irene to remain at the palace disguised as a lady-in-waiting to protect her identity.

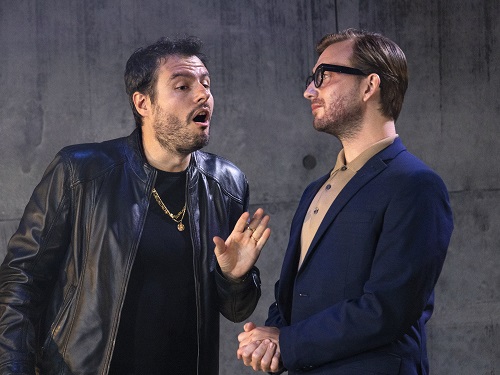

The singing is blissful, though, and stylishly accompanied by the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra conducted by Robert Howarth. The beautiful richness of Raffaele Pe’s countertenor is so at odds with Tamerlano’s maliciousness and the nonchalance of his evil-doing, that the characterisation is instantly intriguing. Winton Dean may have described Handel’s anti-hero as ‘a specialist in mental cruelty’, but this isn’t a Tamerlano hell-bent on villainy for its own sake; rather, a man who really can’t understand why others find his plans – as he moves them like pawns around a chessboard of politics and romance – so objectionable. After all, he is gifting them wives and husbands, freedom, kingdoms … what’s their problem? The ripe sensuousness of Pe’s voice is full of irony, and dressed in leopard-skin, leather and gold lamé, he fully inhabits his character. If he seems psychopathic, it’s precisely because he doesn’t seem to realise quite how dangerous and unhinged he is – as the ease with which Pe dances through the coloratura aptly conveys.

Patrick Terry’s countertenor is of a softer, more reflective hue, and it’s a lovely counterpart to Pe’s shine. It’s been very satisfying to watch Terry progress during the past decade from RAM student, to Kathleen Ferrier prize winner, to Royal Opera House Jette Park Artist and now to a firm and deserved foothold in the profession. Andronico’s slow, lyrical arias of love were heart-meltingly expressive, and he tripped lightly through the roulades too.

There wasn’t a great deal of romantic rapport between this Andronico and Asteria, though, and while that may be a weakness of the libretto, Sophie Bevan seemed a little hesitant initially. She warmed into the role, however, and her attentiveness to the details of the phrasing was notable, especially in the two duets, with Bajazet and Andronico, that open Act 3, where the emotional range – from love to sorrow to vengeance – opened up.

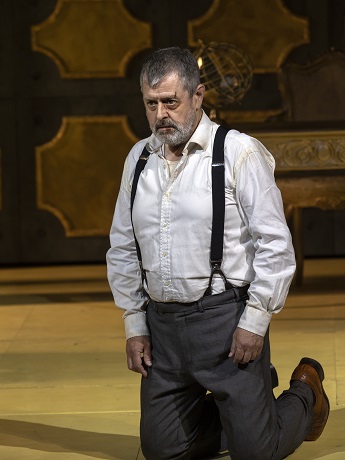

Whatever the title of this opera, the figure at the centre of the drama is Bajazet. Paul Nilon was fittingly noble and heroic, dismissive of pity and driven by defiance. This was a very human portrayal, fire shadowed by frailty. His relationship with his troubled daughter was movingly conflicted. The drama stealthily creeps towards his Act 3 suicide, and Nilon structured the increasing intensity skilfully. Tamerlano declares that if Asteria will not marry him, then he will kill Andronico and Bajazet. The latter saves him the trouble, and Bajazet’s strength and pride prompt a perhaps unlikely volte face which sees Tamerlano permit Asteria and Andronico to marry and declare himself eager to marry Irene – sung here by Lyddon with lots of colour and a vibrant lower register – after all.

The final image, of Tamerlano and Irene feasting, had something of the drama of a Caravaggio. One could not help but feel that Irene might prove more than a match for the all-powerful emperor …

Claire Seymour

Handel: Tamerlano

Tamerlano – Raffaele Pe, Bajazet – Paul Nilon, Asteria – Sophie Bevan, Andronico – Patrick Terry, Irene – Angharad Lyddon, Leone – Stuart Orme, Actors – Alex Comana, Molly Moody, Korey J Ryan, Holly Sonabend, Ray Strasser-King; Director – Daniel Slater, Conductor – Robert Howarth, Designer – Robert Innes Hopkins, Lighting Designer – Johanna Town, Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra.

The Grange Festival, Hampshire; Friday 10th June 2022.

ABOVE: Raffaele Pe (Tamerlano), Paul Nilon (Bajazet), Angharad Lyddon (Irene) (c) Simon Annand