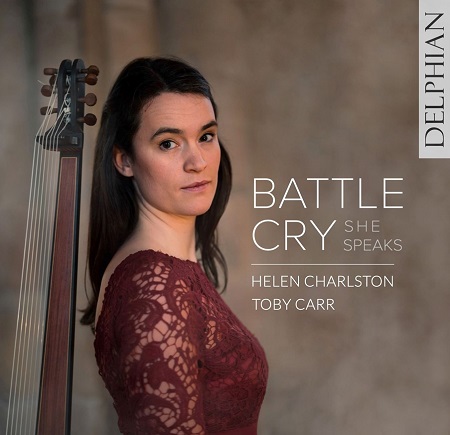

The ‘Battle Cry’ presented by mezzo-soprano Helen Charlston and theorbist Toby Carr in this early- evening Oxford Lieder recital in the Sheldonian Theatre was a distinctively female one, the programme being drawn from their recent release on the Delphian Records label which presents the voices of so-called ‘abandoned women’ – Boudicca, Sappho, Dido, Ariadne, Philomel – but allows them not just to lament but also to lift up their stories and their selves through song.

It’s a programme that is both intelligent and insightful, forging creative connections between the past and present. In the Sheldonian, it was delivered with consummate poise. Charlston has been collecting accolades in recent years: she won first prize in the 2018 London Handel Singing Competition, was a finalist in the 2019 Grange Festival International Singing Competition, won the Ferrier Loveday Song Prize in the 2021 Kathleen Ferrier Awards, and is a BBC New Generation Artist. Her platform manner and presence are assured, and engaging, and she sang the entire programme confidently off-score, communicating with a beguiling directness. Her diction was superb in all three languages heard here, and she demonstrated throughout a discernment in linking text to colour and weight. Her mezzo is full and creamy – though perhaps the bottom register didn’t always carry – and the evenness of her phrasing was complemented by variety of colour, often changing rapidly in response to the text. Carr was alert to every vocal nuance and choice, a true expressive partner, unobtrusive but unfailingly eloquent.

The title of the programme (and disc) derives from a new song-cycle commissioned from composer Owain Park which sets four texts by Georgia Way. Performed at the centre of the symmetrical sequence of items, Park’s cycle builds an intriguing bridge between past and present by reconsidering and reworking the relationship between voice and theorbo. In the first song ‘Boudicca’, the theorbo’s chaconne pattern was initially a sparse tapestry, high and low notes picked out preciously, creating an otherworldly air; subsequently, it filled out gently, consolingly. The vocal line seems to play to Charlston’s strengths: though it is fragmented, plunges low at times (“Romans displace her.”), and employs emotive melismas (“The Thames delivers her.”), the mezzo-soprano made the utterances cohere into something compellingly rich and strange, even though the prominent consonants of the text – “Guttural fragments cradling versions of history/ she never chose.” – sometimes seem unfriendly.

I loved the way Charlston created an absorbing character in ‘Philomela in the Forest’, one that initially stuttered, “You’ll be hooded … silenced!”, but gradually discovered her own desire for solitude. Complementing this self-knowledge, Carr’s initial descending scalic repetitions – the lowest note of which seemed to trigger an eternal, inescapable cycle – found greater freedom, even playfulness, through rhythmic variation and ornament, when Philomela sang to the falcon, “Turn tail, little falcon, fly far away,/ and leave me on my own.” That desired solitude was embodied in the third song, ‘A Singer’s Ode to Sappho’, an unaccompanied, roving exploration of the power of song, the theatrical effect of which Charlston exploited with judicious insight. Only the final song, the longest, ‘Marietta’, seemed less engaging. While structure was intimated by the alternation of the theorbo’s slow arpeggio shapes with more improvisatory, even jazzy, reflections, the progression of ideas loses its way, I feel, though Charlston made sure that the rhetoric of the final exclamation – “The dead breath stale air to sing./ Jealous? Why would I be jealous of the dead?” – was a striking accusatory gesture, quasi-spoken, full of bitter contempt and heated self-belief.

Purcell framed the programme. ‘O lead me to some peaceful gloom’, Bonduca’s Song from Fletcher’s The Tragedy of Bonduca, was notable for the way Charlston and Carr balanced coherence and detail – the “shrill trumpet” embodied by both voice and strumming theorbo, the chromatic lean of the “eternal hush” creating mystery, the “glory” denied the lover who remains a slave to love evoked by tight dotted rhythms. Subsequently, Dido equalled Bonduca’s dignity, her lament refined and regal, but not lacking expressive nuance. A similarly composed, calm performance of Purcell’s ‘Evening Hymn’ made for a comforting conclusion to the programme.

Charlston was at her best, though, in items by Barbara Strozzi and Claudio Monteverdi, entirely attuned to the composers’ impassioned, soul-wracking and mercurial creative responses to their highly emotive texts, and able to respond to every nuance, while crafting phrases of arching expressive meaning. In Strozzi’s ‘L’Eraclito amoroso’ (The loving Heraclitus), Charlston seemed truly to sink into the joy of anguish, relishing the sounds of the text, negotiating the registral leaps with agility and flexibility, as well as accompanying changes of tone and tint that were beautifully dramatic, sighing sensuously. ‘La Travagliata’ was similarly supple and vocally bright, playful at times, but ultimately surprisingly angry in the constant, faithful lover’s rippling demand for a kiss: “Si può dare del baciare/ guiderdon che vaglia meno?” (Is there any recompense which costs less?). Here, and in Monteverdi’s Lamento d’Arianna – which Charlston structured superbly, making the pleading address, “O Teseo, O Teseo mio” ever more pained and touching, and the anger that he remains deaf to her torments a disturbing peak of rhetoric – the virtuosity of both performers was worn lightly but ever affecting, the Renaissance ideal of sprezzatura consummately, artfully realised.

Carr offered what one might call ‘palette cleansers’, a prelude and sarabande by Robert de Visée and Giovanni Kapsberger’s Preludio Quinto, but these gentle miniatures were much more than foils to the vocal intensity, meandering with wonderful freedom, the carefully painted sonic canvas mesmerising.

Despite the title of the recital, these battle cries were really more introspective than rageful. An encore by Strozzi offered some of the playfulness and energy that might profitably have provided contrast earlier in the programme. But, this was an impressively curated and communicated sequence of female stories, the storytellers defeated yet defiant, suppressed yet never silenced.

Battle Cry: She Speaks is available from Delphian Records.

Claire Seymour

Helen Charlston (mezzo-soprano), Toby Carr (theorbo)

Purcell – Bonduca’s Song: ‘O Lead Me to Some Peaceful Gloom (Z.574); Barbara Strozzi – ‘L’Eraclito amoroso’; Robert de Visée – Prelude; Purcell – Dido’s lament (‘When I am laid in earth’); Owain Park – Battle Cry; Kapsberger – Preludio Quinto; Strozzi – ‘La Travagliata’; Monteverdi – Lamento d’Arianna; de Visée – Sarabande; Purcell – ‘Evening Hymn’ (Z.193)

Sheldonian Theatre, Oxford; Friday 14th October 2022.

ABOVE: Helen Charlston (c) Benjamin Ealovega