Elina Makropulos, the ‘heroine’ of Leoš Janáček’s 1925 opera The Makropulos Case (Věc Makropulos), has been alive for 337 years, her longevity prolonged by an experimental potion given to her at the age of sixteen by her physician-cum-alchemist father, Hieronymus Makropulos. In 1920s Prague she is known as the world-famous diva Emilia Marty, but in her wake she leaves shadows of other ‘EM’s – Ellian MacGregor, Eugenia Montez, Elsa Müller. Timeless and ageless she may seem but, now reaching the twilight of her life, she is desperate to find the formula for the elixir, which is written on a document hidden in an old cupboard in the Prus family mansion alongside other crucial papers relating to the interminable Gregor v. Prus inheritance case.

The passing of time, immortality, and the reality of aging and death are thus central concerns in the opera, and Olivia Fuchs’ new production for Welsh National Opera makes this and much else besides abundantly clear no – mean feat given the wordiness of the libretto and the complexities of the legal case that is the ostensible focus of the action. During the Overture, monochrome projections (Sam Sharples) juxtapose chronological apparatus – slowly gyrating cogs, the sands of Time, the regular tick of a metronome – with soft-focus shots of a woman’s face, her mouth and eyes suggesting despair and suffering. As the imagery unfolds, the music, under the superb leadership of conductor Tomáš Hanus, is direct, sinewy, the rhythmic transitions as taut as a watch spring. Beautiful calligraphy in deep black ink flows across the screen: “E M” – the final initial a graceful, curling flourish, a confident assertion of identity.

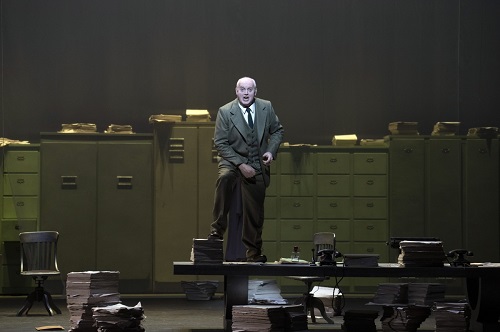

Nicola Turner’s sets are realistic but imaginative and detailed. We begin in Dr Kolenatý legal offices, the dusty document drawers, cluttered desks and paper-strewn floor attesting to the torpor and stagnation of the Prus-Gregor legal wranglings. As Kolenatý (Slovak bass Gustáv Beláček) and his clerk, Vitek (Mark Le Brocq) trawl through the minutiae of the century-old inheritance dispute – impressively, they delivered the knotty legal affairs in swift and engaging fashion – the inert, greyness of the set brings Dickens to mind: ‘Scores of persons have deliriously found themselves made parties in Jarndyce and Jarndyce without knowing how or why; whole families have inherited legendary hatreds with the suit. […] Fair wards of court have faded into mothers and grandmothers; a long procession of Chancellors has come in and gone out […] Jarndyce and Jarndyce still drags its dreary length before the court, perennially hopeless.’ With Emilia Marty’s stagey entrance, the piles of documents concertina upwards to the ceiling, forming dangling, mocking paperchains, their airiness suggestive of the elusiveness of both a legal conclusion to the case and the ancient parchment that Emilia seeks.

A misty, square clock watches over the lawyer’s office, like a moon in a cloudy night sky. And, fittingly, timepieces are compelling images in each Act. Amid the stepladders, dustsheets and silvered mirrors of Act 2’s theatre backstage, an outsize, antique gold clockface leans forlornly, a relic of former glories. The floor is strewn with mounds of roses, like blood-red graves, bestowed by Emilia’s worshippers. After the shock of scarlet, the blanched palette of Emilia’s boudoir in Act 3 sends a shiver, the stark white cold and unconsoling. Atop the large bed perches an ornate silver mantel clock, coolly ticking away the minutes. Monogrammed suitcases scattered around the bed remind us of Emilia’s itinerant life. The details of all three Acts are sensitively lit by Robbie Butler.

Fuchs has a superb cast to serve her conception. The Spanish soprano Ángeles Blancas Gulín embraces every atom of Emilia Marty’s imperious contempt, her swagger and her sensuality. The black bob she sports in Act 1 is replaced by curling, crimson tresses in Act 2, slinky silk giving way to flouncy taffeta. When Emilia whips off the outer layers and dangles them before her admirers like a matador taunting a rampant bull, the danger that she embodies to those who fall under her spell is undeniable. Act 3 sees her attired in a long blond wig and silvery nightgown, as if life-blood and passion are draining. Gulín is a transfixing singing actress, and she seemed to relish conveying Marty’s almost brutal, solipsistic lack of empathy even more that she did her allure. Her tone is not the most ear-pleasing but the strength and heft of her soprano were compelling.

Tenor Nicky Spence was a tortured Gregor, powerfully projecting his longing, rejection and a vulnerability that was painfully human. His anguished exchanges with Emilia Marty were dramatically tense and musically heightened. As Baron Prus, David Stout cut an ambitious, calculating figure, the only chink in his composure when his post-coital anger at Emilia Marty’s ‘emptiness’ almost tipped into self-loathing.

Soprano Harriet Eyley was a fresh, buoyant Krista, her adulation of her older, glamorous colleague convincingly inspiring her own high spirits and ambition. Her playing teasing of Janek was a rare moment of relaxed tenderness, and Alexander Sprague used his light but warm tenor effectively to convey the infatuated young adolescent’s awakened sensuality and crestfallen resignation when both Marty and his father push him aside.

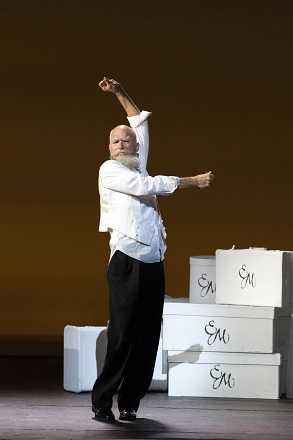

Alan Oke embraced the cameo role of Hauk-Šendorf – Eugenia’s former lover, now enfeebled of mind and body – with flair and good judgement, not over-milking the humour. As he slumped into a wheelchair to be pushed unsympathetically away, he was an emblem of Elina’s transient emotions and callous indifference.

Le Brocq’s Vitek was a confident clerk to Beláček’s officious Kolenatý, and the tenor stayed in role for a scene-change talk-over, in which he elucidated the legal mysteries of the Prus v. Gregor case, aided by a projection of a genealogical tree and a few ironic quips. Again, Bleak House seemed present in the wings – ‘Jarndyce and Jarndyce drones on. This scarecrow of a suit has, in course of time, become so complicated that no man alive knows what it means.’ – but I can’t imagine that many in the audience were in need of the didactic resumé and the tone was at odds with the sung action.

Tomáš Hanus (conducting his own critical edition) communicated the music’s astonishing range – its muscularity, passion, lyricism. Rhythms were precise and lithe, ever-changing, textures infinitely diverse and lucid. The sinuousness of the score seemed to embody the ceaseless complexities and counterforces of the eponymous law suit. And, Hanus was always alert to the singers’ needs. He controlled the pace and shape of the drama superbly, balancing all the elements, utterly in command of the emotional trajectory. I was sitting near enough to the pit to be able to see Hanus mouthing the words of the libretto, living the drama with the singers.

‘What would it be like to live forever?’ Makropulos asks questions about mortality and death, and highlights the ethical concerns when man intervenes in Nature’s cycles of life and death. But, as Olivia Fuchs points out, this incredibly rich opera explores much more besides, “the dehumanising potential of human progress, and women negotiating their power and independence”. One might also suggest that Emilia Marty’s desire to hold onto life is a metaphor for the refusal of the past to cede to the present and the future. In existing for ‘too long’, she brings destruction to the present and denies it life.

And, it is this w,hich Emilia finally understands during the tragic apotheosis of the final Act, when she recalls her love for Pepi, whose actions have determined the fate of so many other lives, and realises that it was this love that gave her life meaning. Now, it all means so little. In this production, this is the moment when the façades crumble and dissolve – literally so, as Emilia throws aside her peroxide wig, revealing a bald scalp, and pulls a diaphanous drape down upon herself, like a shroud. She bequeaths the elixir to Krista, who holds a candle to the corner and consigns eternal life to ashes, as projected flames lick at the shadowy walls of the boudoir. It was a pity that at this performance the Birmingham Hippodrome air-conditioning hindered the paper conflagration, but the stage image remained a powerful one. Transforming Karel Čapek’s philosophical comedy into an emotionally charged psychological drama, Janáček shows us that life only has value because of our awareness of our mortality.

Claire Seymour

Emilia Marty – Ángeles Blancas Gulín, Albert Gregor – Nicky Spence, Dr Kolenatý – Gustáv Beláček, Vitek – Mark Le Brocq, Krista – Harriet Eyley, Baron Jaroslav Prus – David Stout, Janek – Alexander Sprague, Count Hauk-Šendorf – Alan Oke, Komorna (Chambermaid) – Julia Daramy-Williams, Stage Technician/Doctor – Dafydd Allen, Monika Sawa – Poklizecka (Cleaning Lady); Director – Olivia Fuchs, Conductor – Tomáš Hanus, Designer – Nicola Turner, Lighting Designer – Robbie Butler, Video Designer – Sam Sharples, The Orchestra of Welsh National Opera

Hippodrome, Birmingham; Tuesday 8th November 2022.

ABOVE: Ángeles Blancas Gulín (Emilia Marty) (c) Richard Hubert Smith

Hippodrome, Birmingham; Tuesday 8th November 2022.